Race, nation and migration – the blog series reframing thinking on movement and racism.

By Rachel Humphris.

Brexit and the UK’s relationship with the European Union foregrounds questions of identity, nationhood and who is included or excluded. For those identified as ‘Roma’ these are perennial questions as purported ‘European citizenship’ made little difference to their position as Europe’s enduring ‘internal Other’, who have never and cannot ‘belong’ (Sardelić 2019). Roma are always positioned ‘in’ but never ‘of’ Europe. Often overlooked in histories of modern Europe, Roma have been enslaved, forcibly settled and sterilised, suffered state kidnap, and targeted during the Holocaust. Their current experiences continue to reveal the force of stigmatization and racialisation embedded in society, law and governance.

I came to a partial understanding of these experiences through spending 14 months living in Luton, UK, with ‘Romanian Roma’ families (a bureaucratic category used by frontline workers) with the aim of exploring migration, statecraft, race and urban marginalisation. Luton has suffered the brunt of ‘austerity localism’, post-welfare reforms, rising xenophobia, and the dehumanizing ‘hostile environment’ created to make living in the UK so difficult that migrants ‘self-deport’.

I observed the gendered and racialized effects of the hostile environment as migrant households were the subject of ubiquitous value judgements, targeted surveillance and an imposed racialized exceptionalism tending toward differential treatment premised on mythical assumptions (Stewart 2012). For example, mothers were judged on the food they ate, whether their front garden was tidy, the other people in the house (particularly men) who were not part of the ‘nuclear family’ and the disorienting rhythms of the domestic space, which did not map onto prevailing norms of domesticity, intimacy and intensive mothering. While these mothers have a particular experience, these processes are based in deep histories of surveillance and disciplining of the racialized and classed urban poor (Picker 2017).

However, I was also acutely aware that the frontline workers conducting home visits were themselves caught in the entanglements of a retreating welfare state and securitised migration apparatus. Casting aside the usual binary of social care/social control, these observations made me attend to the manifestations of ambivalence and uncertainty for migrant mothers and frontline workers. I shifted my emphasis from ‘state acts’ to ‘state encounters’ to open up the processual and relational quality of how states are made in practice and to account for emplaced and embodied positions of all social actors.

So while frontline workers determine the fate of new migrant families (potentially causing their deportation or state kidnap) they are themselves often racialized mothers, subject to migration control and invested in proving themselves as ‘good citizens’ resonating with Cohen’s (1999) notion of ‘advanced marginalisation’. They must negotiate their way through a complex, constantly shifting and messy terrain of migration policies, border policing and surveillance. They must reconcile these duties with their professional commitment to an ethics of care, often taking on work well beyond their formal role and the hours that they are paid (through processes of New Public Management they are employed in short-term, target driven, precarious contracts at the lowest end of the local state). They carry with them enormous and contradictory burdens, responsibilities and anxieties with the fate of new migrant families and their futures at times in their sole hands.

These intimate state encounters are one instance where decisions about who belongs and who deserves discretionary extra support rests on the strange and unsettling mingling of established categories. These citizenship decisions emerge at the intersection of public and private, formal and informal, political and personal. Drawing inspiration from Mbembe’s observations of colonial governance (2001: 28), this research showed that governing political belonging through the home space does more than confuse the public and private: it depends on and reproduces that confused space to ensure the continual reproduction of marginalisation based on raced, classed and gendered hierarchies.

As critical race, gender and queer scholars have long pointed out, the distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’ is most fundamentally drawn in the intimate sphere. From British imperialism to the present day, racialized relations have come to be shaped and governed through intimacy (McClintock 1995; Stoler 1995). My work has tried to draw a line from these debates to the role of the family and the domestic in the contemporary UK state and how they relate to conceptions of nationhood, identity and belonging today.

The stories of new migrant mothers and those tasked to govern them are not often heard. Legal migration statuses are proliferating and becoming more precarious. Brexit seems unlikely to reverse the trend. Austerity is still biting hard and likely to continue in the current context of a stagnating economy and casualties of COVID-19. The privatisation of services is carrying on apace creating complex relationships in frontline provision.

Marginalised families, like the Roma in Luton, are more likely than ever to fall through the gaps or become subject to bordering, sometimes from those who have the best of intentions but work in a harsh and broken system. In this context, the most mundane everyday actions in the home become crucial for how families can secure a safe status in the home-land. This research raises fundamental questions about the types of homes – and the type of home-land – we want and what we need to change to achieve them.

Rachel Humphris is a Lecturer in Sociology and Politics at Queen Mary University of London. She is a political ethnographer whose research and teaching focuses on immigration and citizenship, urban governance, gender and race.

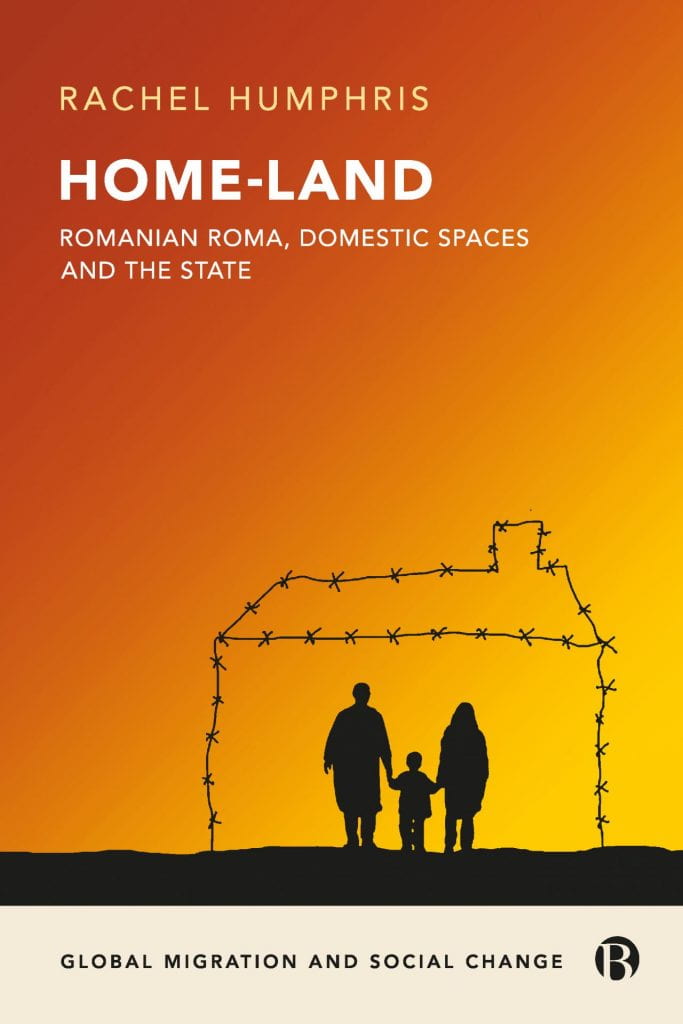

Home-Land: Romanian Roma, Domestic Spaces and the State (2019) is available from Bristol University Press.