By Amanda Schmid-Scott.

Forty minutes into the bus journey that takes me from the bustling streets of Bristol’s city centre, through Bishopston and Horfield, and slowly along Gloucester Road, with its vibrant array of independent shops and cafes, we eventually head onto the busy dual carriage way. As we leave the shopfronts and people on foot behind, the bus eventually stops. At the side of the dual carriage way, I disembark and cars rush past at 60 mph. In order to cross to the other side of the road, I am forced to make a run for it when there is a gap in the traffic. I arrive at Patchway police station which, approximately seven miles from central Bristol, is the official immigration reporting centre for the city and the surrounding area. Immigration reporting, often referred to as ‘signing’, is a compulsory requirement for migrants without legal status, including asylum-seekers who are awaiting a decision on their asylum claim. Framed by the Home Office as an administrative procedure, migrants are required to present themselves regularly (usually once a week, or bi-weekly) to one of 13 reporting centres located throughout the UK as a condition of immigration bail.

Today is my first day volunteering with Bristol Signing Support, a group who regularly attends the reporting centre at Patchway to offer practical and emotional support to migrants in what can be a frightening and often isolating experience. This is due to the fact that the Home Office, as well as using reporting appointments as a means of keeping track of the whereabouts of migrants pending legal status, utilise these sites to target potential deportees. This means that each time an individual attends their reporting appointment, they face possible detainment and removal from the UK.

I volunteered with the Bristol Signing Support group for a year from May 2017, and as part of my doctoral research conducted interviews with asylum-seekers subjected to immigration reporting, as well as fellow volunteers and asylum support workers involved in various local community organisations. Over time, I recognised how, alongside the often extreme fear many migrants experience of being detained during their reporting appointments, these sites also impose more surreptitious, mundane forms of harm. Accounts of those subjected to reporting requirements reveals how these often hidden and hard-to-reach reporting sites enforce a continuum of violence, steering migrants towards subjugation, destitution and removal (Schmid-Scott, forthcoming).

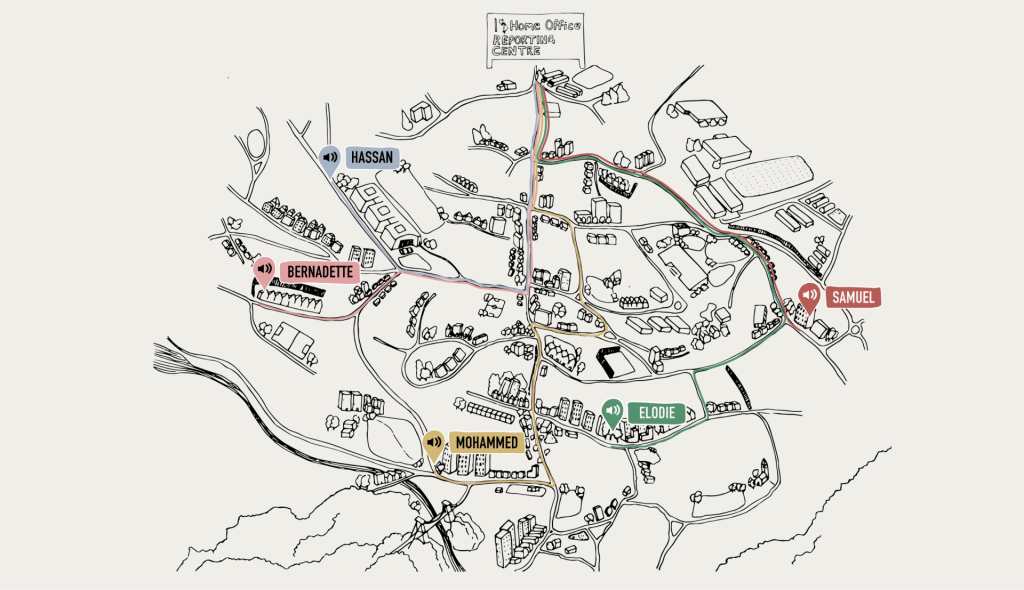

With funding I obtained during a postdoctoral research fellowship at Newcastle University, I collated a selection of my research interviews to produce Reporting Sounds, an interactive website enabling users to explore the impact of immigration reporting on the lives of asylum-seekers living in the UK. Designed in the form of a map of Bristol, the website combines hand-drawn pen-and-ink illustrations with audio-recorded stories from my field research. These testimonies situate the various harms that are imposed on asylum-seekers in relation to their immigration reporting requirements, invoking the ways in which the impact of reporting affects their everyday lives. These experiences are focused around five individual stories, each indicative of the continuum of violence which constitutes the UK’s asylum process. By centring on their experiences of immigration reporting, these stories connect the administrative systems and sites of UK border control measures with everyday encounters with suffering.

At times, this suffering emerges through more surreptitious and mundane spatiotemporal harms, implicit in the obligation to travel repeatedly to these often remote, difficult-to-access sites, very often for years on end. Mohammed describes requesting to have his reporting schedule reduced – a request that was denied – and how he must pay for the bus to and from his appointments, which is a huge financial burden for those that are already living below the poverty line. Likewise, Hassan recounts not having enough money to pay for the bus fare, and tells the Home Office ‘you can arrest and detain me again’. The inclusion of each individuals’ journey times and travel costs, signalling the proportion of time and money these journeys necessitate, further illuminates the everyday burden regular reporting entails.

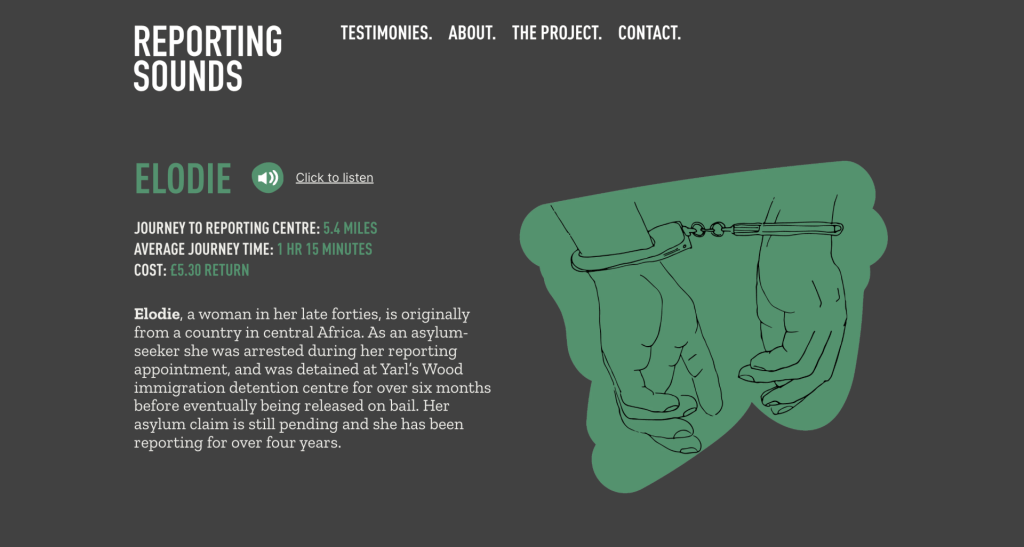

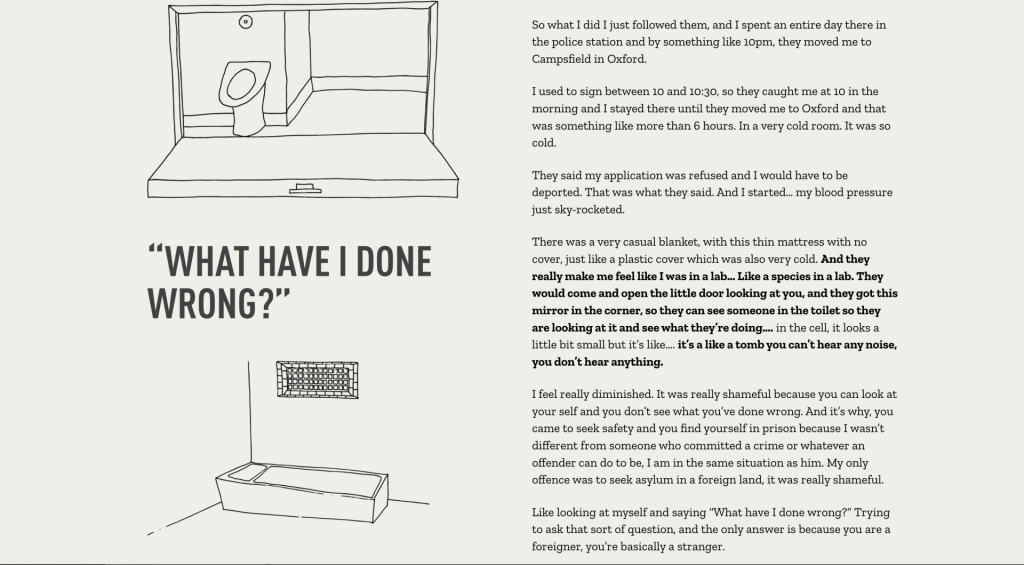

At other times the harms that reporting imposes materialise through the more overt violence of arrest and detainment. Elodie’s experiences of being detained during her reporting appointment, where she suffered a panic attack, point to the danger these sites hold in repeatedly threatening asylum-seekers with potential arrest and detainment. For Mohammed, the fear of being detained affects his sleep prior to signing days; he describes how ‘you never know when you’re coming back’. Samuel also talks of being detained during his reporting appointment within the onsite holding cells and reflects on the shame he felt in being detained ‘as someone who committed a crime’. Bernadette’s account reveals how the threat of being detained is felt beyond the walls of the reporting centre, as she explains: ‘I’m still looking through my window all the time. Between six o’clock and eight o’clock in the morning, that’s what time they normally come.’ As these accounts show, the threat of a possible detainment and subsequent forced removal attempt is intimately felt by individuals, making it an extremely stressful process, and yet one which they must repeatedly engage in, often for years on end.

Creating an archive

By creating an interactive, auditory web-archive of asylum-seekers’ testimonies, Reporting Sounds sheds light on the relatively unknown border control practice of immigration reporting and provides the opportunity for the public to explore its everyday impact on the lives of asylum-seekers in the UK. As Sara Ahmed’s work has identified, archives are tethered to the question of whose experiences are worth preserving (Ahmed 2006), and through my own attempt at creating an archive of asylum-seekers’ testimonies, this form of data gathering holds space for these otherwise little-known-about and hidden experiences. Using the form of a map to situate their testimonies, and drawing attention to their less-visible sites of impact (that is, the home, the body, the reporting office), imposes a form of ‘counter-mapping’ which, as Craig Dalton and Liz Mason-Deese argue, allows us to challenge and reimagine dominant spatial imaginaries and how certain populations move through these spaces (Dalton and Mason-Deese 2012). While each of these five stories is deeply personal to the individual’s experience of reporting, they are also reflective of the current, contemporary political moment, in which the UK government has placed hostility towards and the removal of asylum seekers at the front and centre of its politics. The last, sixth box is left open for individuals to share their own experiences of reporting.

In May 2024, I will be hosting an event with Migrants Organise in London, to launch the website and to invite the public to learn more about immigration reporting and the lived experience of asylum. If you would like more information, please get in touch.