By Simón Palominos Mandiola.

In 2023, Chileans worldwide marked the 50th anniversary of the 1973-1990 civilian-military dictatorship, which aimed to dismantle decades of progress in wealth redistribution, cultural development and democratisation in Chile. Alongside arrests, torture and murders, exile became a widespread repressive tactic, with over 200,000 individuals forced to leave, significantly altering migration patterns. This, combined with restricted immigration policies based on a narrative of national security, resulted in Chile experiencing a negative migration rate for the first time in the history of national records. Exile, a tragedy marked by state aggression, led to family separation and uncertainty in foreign lands.

The concept of exile, along with migration, understands individuals as bound within national borders, often portraying migrants as anomalies in their new societies. This prevailing national lens in social sciences introduces the epistemological bias of methodological nationalism, limiting interpretations of mobility. Scholars such as Nina Glick Schiller and others advocate for a transnational approach, highlighting the re-creation of societies of origin in new environments. Alternatively, John Urry proposes a focus on mobilities, prioritising movement over fixed points. Understanding migration within regimes of mobility that promote, force or hinder mobility, as described by Glick Schiller and Noel Salazar, acknowledges the power dynamics affecting movement. This mobility paradigm underscores politics, economics and culture in reshaping human migration. The arts, notably music, also significantly influence this phenomenon.

Thousands of Chileans found refuge in Latin American and European countries during the dictatorship. Musical artists such as Isabel and Ángel Parra, Patricio Manns, Quilapayún, Inti-Illimani and Illapu, among other members of the New Chilean Song movement, found asylum in countries such as France, Germany, Sweden and Italy. In these countries, solidarity movements emerged involving artists, activists and workers who collaborated with local trade unions, intellectuals and political parties. Drawing from Chilean culture, particularly music, poetry and gastronomy, this solidarity movement fostered a sense of belonging and garnered European support. The movement established an international network, facilitating artist circulation and making the Chilean political situation visible in Europe.

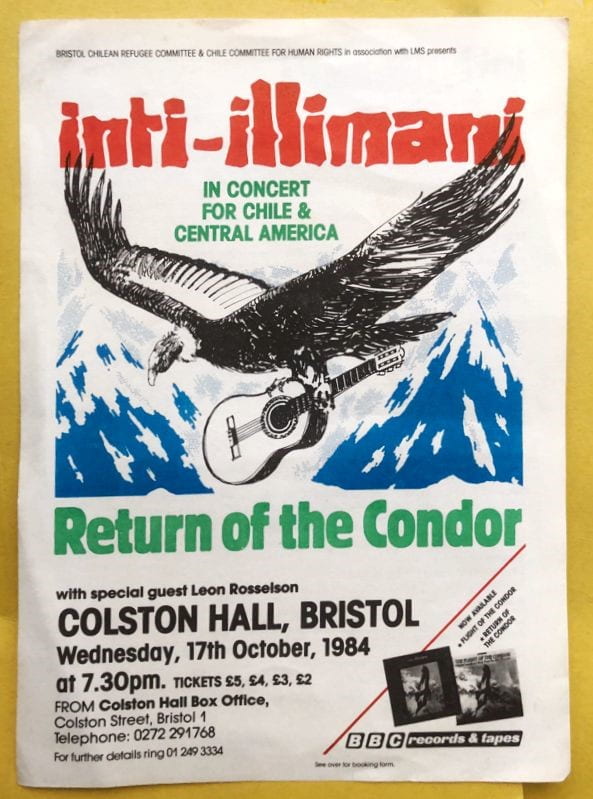

During this time, around 3,000 Chilean refugees arrived in the United Kingdom. In October 2023, at the University of Bristol, we came together with three members of this Chilean community residing in the UK to explore how musical practice serves as an exercise of memory that shapes new futures. Language specialist Carmen Brauning and photographer Luis Bustamante shared the solidarity work they have carried out in Hull and Bristol since arriving in the UK in 1974 through a grant from the World University Service. In 1983 Carmen and Luis organised a concert in Bristol with the group Quilapayún and in 1984 another concert with the group Inti-Illimani.

The organisation of the concerts proved to be challenging due to the diverse experiences of mobility and political strategies of the Chilean community in Bristol. Despite the challenges, the events provided a way not only to keep a connection with Chile, but also, crucially, to portray the resilience of the community in the UK. Stefano Gavagnin et al. have suggested that these community organisations carry out supportive activities for other more crucial ones in the musical field, such as musical performance itself. However, I agree with Ignacio Rivera-Volosky that these organizations are part of musical, identity and political performance in both Chile and the UK. In this sense, the concerts in Bristol mark the end of what we can call the period of the ‘closed suitcase’, of the hope of a prompt return to Chile, and inaugurate the period of the ‘open suitcase’. From there, the Chilean community, now also British, had to face the challenge of their own uncertain future and that of their children in the UK with courage. To this day, Luis uses his camera to portray social movements in Europe and Latin America. Meanwhile, Carmen has taught at the University of Bristol, and she continues welcoming international students and inspiring future artists and researchers.

Another speaker at our event was Mauricio Venegas-Astorga. A musician inspired by the New Chilean Song movement, Mauricio arrived in the UK in 1977. He has collaborated with Chilean and British artists in groups such as Incantation and Alianza, and with British composer Richard Harvey and Australian guitarist John Williams, among others. Mauricio’s music blends Latin American and European folk influences, incorporating elements from the Western canon and electronic music. His compositions avoid essentialist portrayals of origin, focusing instead on narratives of movement and transformation. Thus, the artist’s work creates a new space in which the experience of exile, migration and identities – inhabited both in Chile and the UK – can coexist.

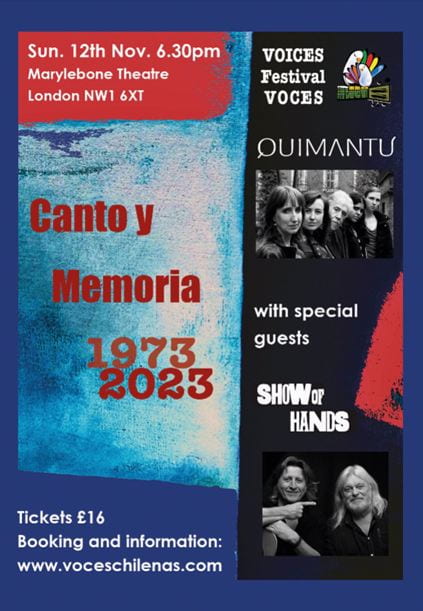

Since 1981 Mauricio has led the group Quimantú, which comprises members from Latin America and Europe. Through the group he fosters a diverse musical landscape and promotes cultural exchange through educational programmes and festivals. Examples of this are the Ethnic Contemporary Classical Orchestra (ECCO), composed of children and young people of various nationalities, and the Voces Festival, created to give space to Latin American artists living in the UK. Through the use of different musical languages and instrumentation, the work of Mauricio, Quimantú and ECCO contributes to erasing borders and creating a collective musical experience. Their work helps us imagine a society in which we recognize differences without building hierarchies. Earlier this year I recorded an interview with Mauricio, along with Quimantú members Laura Venegas-Rojas and Rachel Pantin, where we delve deeper into their mobile experience and the significance of their work. You can listen to our conversation here.

Carmen, Luis and Mauricio’s stories are just a few among many. Numerous individuals and organizations strive to preserve memory and address contemporary issues in Chile, the UK and beyond. Examples include the El Sueño Existe festival in Wales, the media outlet Alborada, Bordando por la Memoria project, and the Chile Solidarity Network. Their efforts illustrate how remembering reshapes the experiences of Chilean and British communities in the UK within the unequal mobility regime established by exile. Memory is not merely a transnational re-creation of Chile but a recognition of past and present experiences, shaping future narratives beyond exile. Through music, arts and culture, memory guides us in envisioning new futures.