Letter from Afar – the blog series about life and research in the time of COVID-19.

By Angelo Martins Junior.

Dear friends

Two months ago the governor of São Paulo decreed a state of emergency and social isolation measures to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time, I was in São Paulo, conducting fieldwork for the ERC project I am working on, ‘Modern Marronage? The Pursuit and Practice of Freedom in the Contemporary World’. The project uses histories of Atlantic World slavery and the means by which enslaved people sought to escape it to guide research on marginalised people’s efforts to move closer to freedom today. So, my days are now mostly spent reading about the history of slavery and its aftermath, and anxiously following news on the Covid-19 pandemic, topics that are closely entwined in the Brazilian context.

Here, as elsewhere in the world, the Covid-19 crisis has illuminated existing inequalities. Besides the massive division between those who can afford access to high quality health care and those who cannot, much of the country’s population simply cannot enact the practices recommended by the World Health Organisation to prevent contagion, such as washing hands or social isolation: 38 million people (41.4% of the labour market) are informal workers; more than 100,000 are homeless; 31 million lack access to a water supply system; 13.6 million live in the thousands of favelas spread across a country that is twice the size of the European Union.

Bolsonaro’s deny and defy approach to the Coronavirus pandemic has already been widely reported in the international media. Over the past month, the President has claimed that the Covid-19 crisis is a media fabrication and trick, or a ‘little flu’. He has also attacked scientists and fired his Health Minister for defending and promoting social isolation; urged people to go on demonstrations against their governors and isolation measures. Bolsonaro mobilises his support with a narrative that places the economy and the virus in competitive opposition, claiming that he is trying to save lives by demanding an end to social isolation, since hunger is a far greater threat to the mass of Brazilian people than a ‘little flu’.

Hundreds of his supporters (video 1) have taken to the streets across large cities in Brazil, waving Brazilian flags, calling the pandemic a communist farce, chanting and shouting violent, nationalistic and authoritarian slogans, asking for dictatorship/military intervention, and mocking death (video 2). Many people have been physically attacked by demonstrators (video 3), while others have suggested killing governors who have decreed social isolation.

These demonstrations are visceral testaments to two things that go hand in hand in Brazil – first, the absence of belief that the state has any role to play in providing for people, and second, a violent disregard for life. Instead of asking why the state is not providing for people so they can safely stay at home, the idea that people will die from hunger if they are not allowed to work individualises the problem and fosters violent sentiments towards those who defend social isolation measures.

Many will rightly link the popular response to the pandemic to neoliberal politics and its individualising social enterprise. It is true that, from the 1980s, neoliberal policies, and their individualising ideological commitments, have been normalised in Brazil, translating all social problems into matters of individual misfortune or misdeed. We can say, indeed, that the ‘neoliberal rationale’ has become a hegemonic feature of the Brazilian cognitive political struggle as well as in people’s minds. This could help us understand why so many people do not see the state as responsible for caring for its population, but instead applaud its efforts to send them to work to avoid dying from hunger even when this means spreading a virus that will kill thousands.

But we also need to remember that in the colonial and post-colonial order of Brazil, violence, disregard for (particular) lives and state repression have been almost omnipresent features. Brazil was the last country to abolish slavery, after having enslaved 4.9 million Africans or 40% of the total number forcibly taken to the Americas. To transform people into slaves, it was necessary to continually repeat acts of violence designed to impress upon the enslaved the knowledge that they were nothing but slaves, with no existence conceivable except as an appendage to the master who owned them. Violence was not only a matter of punishment, but something core to the existence of the enslaved, the masters and the whole system of slavery. For centuries, the mass of people in Brazil were condemned to live in a society where their own social status and very existence was dependent on perpetuating and/or submitting to acts of violence, and this has had great consequences for later generations, long after ‘emancipation’.

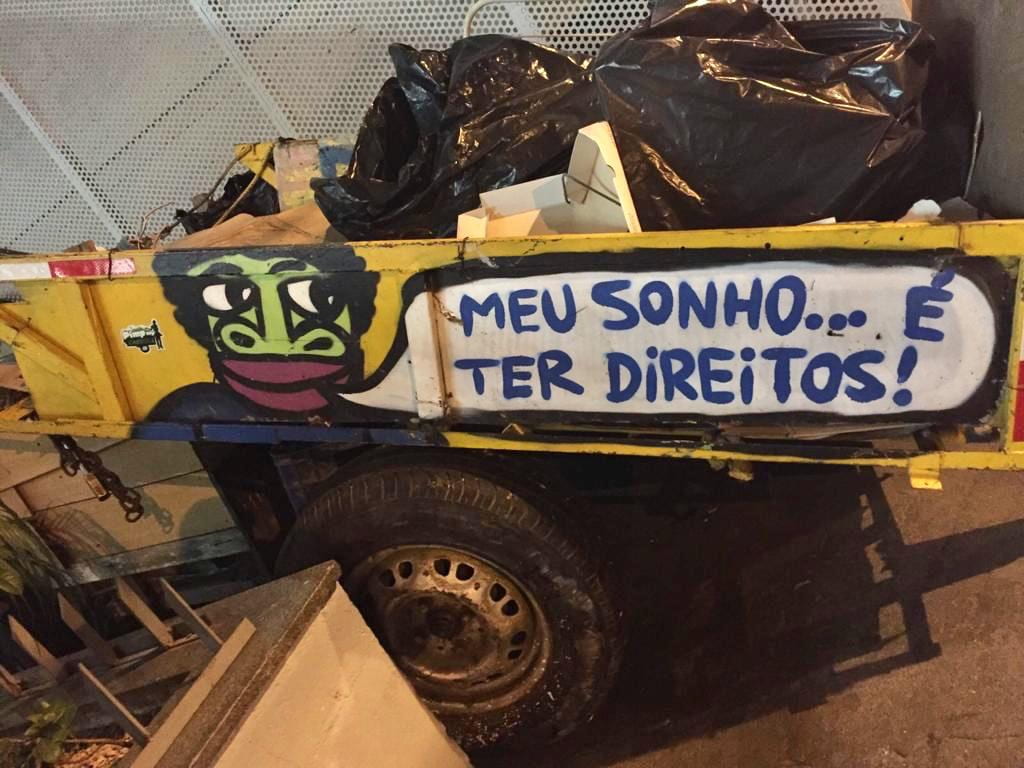

After abolition, an entire class of black and mixed people – the formerly enslaved and their descendants – as well as lighter skinned poor Brazilians were left to their own fates, having to survive in the poor peripheries of large urban centres. They have been marginalised both in the configuration of urban space and in the labour market, dealing with daily exclusion and discrimination. In Brazil, there was never a welfare state, as in Western Europe, which could attempt to remedy such inequalities by providing the basic social rights and protections required for this population to be able to live with dignity. In fact, after independence, almost all governments that have tried to promote social justice and diminish social inequality were impeached or suffered a military coup. In this context, violence has continued to be an important element in Brazil’s social order.

The descendants of the enslaved and lighter skinned poor Brazilians have historically faced a discourse of degradation, rejection from the human commonwealth, and state violence – often being executed on the streets by the police. They are the ones now struggling in the favelas, being told to go back to their already precarious, low paid and insecure work to avoid dying from hunger in a moment of health crisis.

As Stuart Hall has noted, it’s difficult to work through the question of how violent colonial pasts inhabit the historical present. Yet there can be no doubt that this past still reverberates in Brazil’s socio-political-economic structures, as well as in its collective psyche today. Unbidden, our history shapes a present in which the state and many ordinary people place no value on the lives of millions of their fellow beings, and are not only willing to allow death en masse but often violently to attack those who act, symbolically or materially, to preserve the lives of all alike.