By Rachel Randall.

On 19 March it was confirmed that Rio de Janeiro’s first coronavirus-related death was that of Cleonice Gonçalves, a 63-year-old domestic worker who suffered from co-morbidities. When Gonçalves fell ill on 16 March, she was working at her boss’ apartment in the affluent neighbourhood of Leblon, in the city of Rio. Her boss had just returned from a trip to Italy where COVID-19 had been rapidly spreading. She had not advised her employee that she was feeling sick. Gonçalves’ family called a taxi to bring her from the state capital to her home-town 100km away. It took her two hours to arrive. She entered hospital the same evening and died the next day. Her story exemplifies the fact that it was Brazil’s ‘jet set elite’ who first brought COVID-19 into the country, as Maite Conde points out, but it is the poorest who are now at greatest risk of dying from the disease as it ravages urban peripheries. Unlike her employee, Gonçalves’ boss, who tested positive for COVID-19, later recovered.

Gonçalves’ case is not an isolated one, as Luciana Brito explains. Domestic workers are among those most vulnerable to the pandemic. While many employers have remained at home, 39% of monthly-paid domestic workers (mensalistas) and 23% of hourly-paid cleaners (diaristas) continued their labours in spite of the lockdown, frequently out of economic necessity – often residing with their bosses or travelling substantial distances by public transport to reach them. Of the country’s six million domestic employees, over 90% are women and the majority are black (Cornwall et al. 2013). As Angelo Martins Junior has argued, it is the descendants of enslaved Brazilians who occupy the jobs that put them at greatest risk and who are being encouraged to return to their precarious, low-paid work in order to continue feeding themselves and their families.

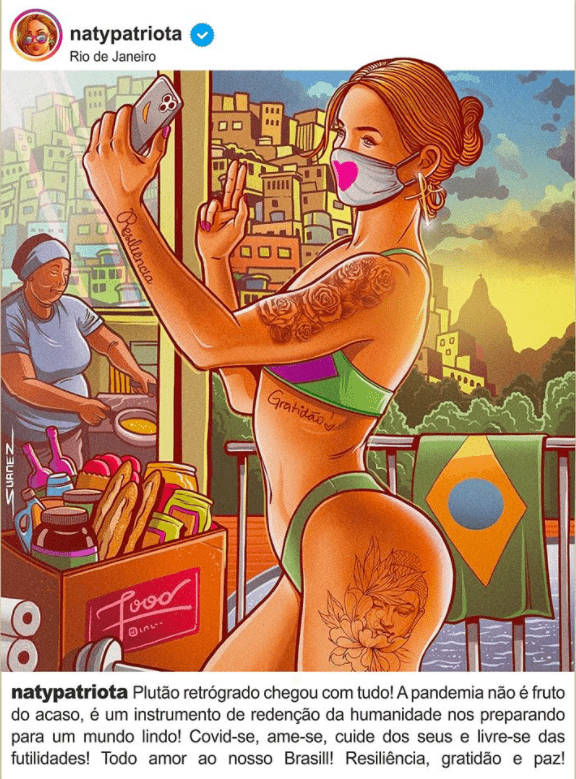

In Brazil, domestic workers have featured at the centre of debates about the country’s high levels of socio-economic inequality, its legacy of slavery and the relationship between the private and public spheres for some time, including in its cultural production (as I have discussed in an article about contemporary Brazilian documentary). In the wake of COVID-19, these workers have become a powerful symbol in the media for the ways that the virus is exacerbating existing inequalities in the country in terms of mobility, income security and housing. The artist Cristiano Suarez has published a pair of illustrations that explore these dynamics on his Facebook page. They serve as parodies of Instagram posts made by young, white influencers in upmarket apartments who remind their followers to prioritise their well-being and relinquish negative energies during quarantine, while their domestic employees can be glimpsed in the background maintaining their glamorous lifestyles. Sadly, some social media content shared by real employers to ‘celebrate’ their domestic workers’ return to work has been actively degrading, including a video posted by vlogger Luan Tavares who recorded his employee cleaning his bathroom as he joked about reducing her wages due to the crisis; the video was spotlighted on an episode of Greg News (the Brazilian version of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver) dedicated to domestic workers.

The debate about how employers should treat domestic workers during the pandemic has been heated. 39% of bosses have dismissed their employees, leaving them without a salary, a situation that worst affects hourly-paid cleaners who do not have a formal contract and are not eligible to benefit from the government’s emergency financial package. Meanwhile, in several states domestic employees were classified as essential workers, thereby obliging them to continue working in spite of the risks. This decision draws attention to the ways that paid domestic work has historically been treated as ‘exceptional’. The Constitutional Amendment on Domestic Work (‘A PEC das domésticas’) implemented in 2015 by the Workers’ Party government represented an important attempt to redress this by aligning domestic employees’ rights with those of other workers. It has been called ‘the second abolition of slavery’.

Ultimately, pressure from domestic workers organisations led the Brazilian Ministry of Labour to state in April that domestic employees should not be made to come to work and should be guaranteed pay while their employers are self-isolating. Despite this, Sérgio Hacker – the mayor of Tamandaré municipality in Pernambuco – and his wife Sari Corte Real, continued to treat the services of their domestic employees’ as ‘indispensable’. The couple, who are white, were both infected with COVID-19, as was their Afro-Brazilian employee Mirtes Renata Santana de Souza, who went to work at their apartment in the state capital Recife on 2 June, taking her five-year-old son Miguel with her as no creches were open.

While Real was having a manicure, Souza took her bosses’ dog out to the street, leaving Miguel with Real. Miguel, who wanted his mother, entered a lift in the apartment block. CCTV shows Real speaking to Miguel in the lift and pressing a button for another floor. Miguel got out on the ninth floor and fell to his death. Real is under investigation for manslaughter. The event – which coincided with the Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd – horrified many Brazilians who took to the streets demanding justice for Miguel.

Brito has explained how Real’s disregard for Miguel’s life epitomises the white supremacy still so prevalent in Brazilian society. As the country’s economy begins to re-open, despite having the second highest death toll in the world, there seems little hope that the lives of domestic workers and their families will be better safeguarded. After all, President Jair Bolsonaro was the only elected deputy to vote against the Constitutional Amendment on Domestic Work when he sat in the National Congress in 2012.

Rachel Randall is Lecturer in Hispanic Media and Digital Communications (School of Modern Languages, University of Bristol). Her current research explores cultural representations of paid domestic workers in Latin American film, documentary, digital culture and literary testimonies (testimonios).

This blog post was first published on the MMB Latin America blog on 6th August 2020. Related MMB blogs: ‘To stay home or go out to work? Brazil’s unequal modes of COVID-19 survival‘ by Aline Pires, Felipe Rangel and Jacob Lima, and, ‘A violent disregard for life: COVID-19 in Brazil‘ by Angelo Martins Junior.