By Nariman Massoumi.

I never talked to my father about his experience of arriving in the UK until I made a film about it. Baba 1989 is about his memories of arrival following four years of separation from me, my mother and siblings. We left Iran as refugees in 1985 during the Iran–Iraq war and sought asylum here. My father could not get a visa and had to live in Germany for two years. Without the pretext of making a film, it would have been difficult for either of us to have a conversation on the subject. In the film he describes painful memories of trying to reintegrate into the family, our estrangement from him, the language barriers, lack of work and money, our dire living conditions and his inability to connect to anyone.

Film equipment can often be seen as a barrier to achieving intimacy with a subject. In producing films about one’s parents or family members, the reverse is often the case. When interviewing my father, the presence of the audio recording device introduced a witness, an imagined audience beyond the confines of my parents’ home that allowed him to recall memories of emotionally fraught past events to me for the first time through a performance for others – and for me to vicariously recall my own childhood memories of the same events (as a nine-year-old) through his recollection. He spoke mostly in English and in third person (‘my children’) and only intermittently slipping into second person (‘you’ or ‘your mum’). Perhaps the desire to distance himself from the events resulted in this shifting mode of address.

My documentary film practice has explored my family’s personal experiences of migration, our resettlement in Britain and its relationship to the history of the Iranian diaspora, the Iranian revolution of 1979 and Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988. Documentary filmmaking that engages the participation of a filmmaker’s own family or kin as central subject is what Michael Renov (2004) terms ‘domestic ethnography’. The reciprocity and interplay entailed by a close family tie by this mode of documentary filmmaking plays at the boundaries of self and other, filmmaker and subject in a unique way. A fragile balance exists between ethnographic exploration and an autobiographical pursuit for self-knowledge and cannot be strictly reduced to either. The filmmaker and subject’s intimate connection renders an outsider position difficult (if not impossible), and yet a degree of separation between subject and filmmaker is still retained.

For second generation migrant filmmakers like myself, a parent or grandparent embodies a particular cultural history of migration (Russell 1999) meaning domestic ethnography becomes ‘charged with anxieties about losing access to the parents’ past as a consequence of displacement’ (Berghahn 2013, p. 90). To that end, family photographs, home movies and videos become privileged cultural artefacts due to their role in articulating and mediating memories across generations offering evidence of people and places, kinship and continuity. You can see this in a wide range of films such as Italianamerican (Martin Scorsese, 1974), The Way to My Father’s Village (Richard Fung, 1988), History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige (Rea Tajiri, 1991) or I for India (Sandhya Suri, 2005). Family visual archives take on an increased significance for migrants who have experienced involuntary displacement where the continuities of family life and memory have been disrupted by social upheavals or where the range of available sources are scarcer, and susceptible to loss or obliteration. Yet as highly coded and selective forms of visual communication that focus on the ‘high points’ of family life, they are also unreliable records of family history, reasserting the image the family has of itself and its own unity in order to reinforce its own integration (Bourdieu 1990). Domestic ethnography therefore involves ‘memory-work’ (Kuhn 2002), a form of archaeological detective work to investigate the coded or hidden meanings of family photographs or home movies.

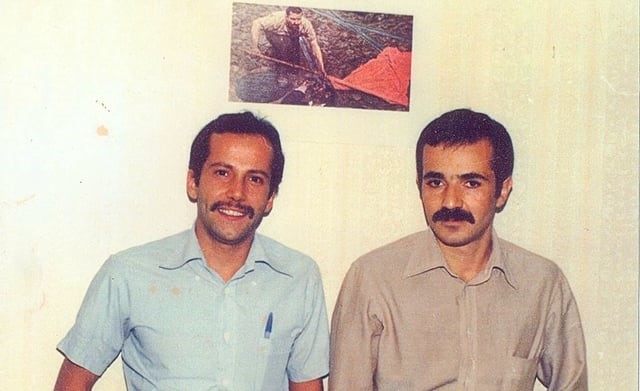

Memory-work takes on significance when engaging with visual archives of historical events I did not directly experience that still conjure up emotional ‘memories’. For example, Baba (2011), an earlier film I made about my father, centres on an iconic photograph of him and my uncle on their release from prison as political prisoners under the Shah’s military dictatorship in 1978 during the Iranian Revolution. The poster behind them is a socialist realist painting called Raising the Banner by the Russian painter Geli Korzhev (1925 – 2002), adopted by an Iranian Marxist guerrilla group. While the photograph was taken before my birth, it stirs up deep feelings in me and connects me to the historical moment through my relationship with the men photographed and what Marianne Hirsch (1997) terms ‘postmemory’ – an affiliative form of memory passed on between family generations ‘by means of the stories, images, and behaviours’ and through ‘imaginative investment and creation’ rather than direct experience. The photograph evokes the unrealised hopes and aspirations of a revolutionary generation, a ‘subjunctive nostalgia’ (Malek 2019), an imaginative reflection on what could have been. It is also shaped by knowledge of political defeat and what is not apparent in the photograph: my father’s incarceration, detention, experience of political violence and psychological trauma written on his body in the present.

In what she terms ‘intercultural cinema’ Laura Marks (2000) identifies a ‘haptic visuality’, a way of conveying cultural memory through a tactile and physical sensibility, which she sees as evident in the work of diasporic filmmakers responding to the gaps and silences in recorded history. In that sense, the investigation and disclosure of my family memories through domestic ethnography is not simply driven by a personal investigation or the anxiety of my parents’ histories being lost into oblivion. The privileging of migrant family memories has a wider political intention, as Berghahn argues, responding to ‘inequities of power and visibility’ through an ‘impassioned plea for the inclusion of memories of the marginalised and the pluralisation of the cultural memory of the host nation’ (2013, p. 116).