Borderland Infrastructures – an MMB special series exploring the material and symbolic infrastructure of border regimes in the port cities of Calais and Dover.

By Juan Zhang.

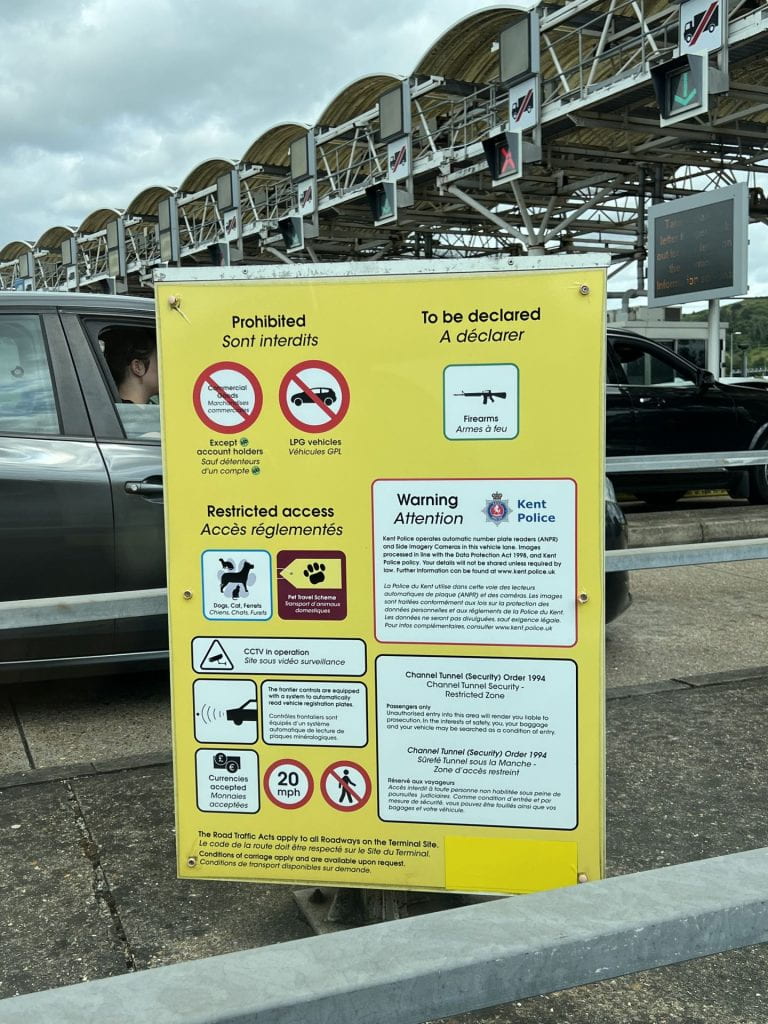

At the Dover border crossing I sat in the backseat in silence waiting for questions from the immigration officer inspecting the four passports we handed over together as a group. While neighbouring lanes saw vehicles swiftly passing through with only a small pause, our officer meticulously examined my Chinese passport among three British ones. ‘He’s looking for my Schengen visa,’ I murmured to myself. I hoped he’d find it soon. On that passport, there were four expired Schengen visa stickers mixed with several other entry visas I had to obtain as a Chinese national. Determining the validity dates on these stickers required sharp eyes and patience. Finally, the officer raised his gaze from the documents and directed his attention to us – what work do you do, and what’s the purpose of your visit?

Border delays and extended examinations at checkpoints were no strangers to me, but I couldn’t shake the thought that my colleagues might have crossed faster without me. This interruption reminded me how borders could stretch or compress space-time unequally and regularise a particular kind of asynchronicity to justify delay and waiting, and smooth border-crossing should not be taken for granted (see Anderson 2020 on this point). My Chinese passport added an extra ten minutes to the journey – a minor inconvenience after all. But what if I did not possess a valid visa, or if I were not accompanied by my British colleagues who answered immigration queries, or in a more extreme scenario, without a passport or any form of identification? What could a non-EU, non-UK citizen expect at this crossing in that case?

During the week of our two-day visit to Calais, more than 1,300 migrants crossed the English Channel in small boats, setting a new record of unauthorised crossings in recent years and fuelling intense public debate on the UK and French governments’ failure to ‘stop the boats’. Most of the migrants lacked any documents or legal papers and had likely endured weeks or months of waiting in Calais before their risky attempts (Sandri 2018). If the border added a 10-minute delay for me, for migrants and many others on the move, the border could feel altogether impenetrable as no ‘safe passage’ was possible due to tightening British immigration control and bureaucratic red tape (King 2016). People on the move had been stopped and forced to camp out in Calais, where thousands were stuck in limbo in the so-called Jungle – makeshift campsites of deteriorating conditions outside the city of Calais between 2015 and 2016 – until they were forcibly evicted by the French authorities (Van Isacker 2022).

The Jungle may now be abandoned and appear empty, but this does not mean people have stopped coming or are no longer trapped. Calais-based activists explained to us how the French border police and CRS (Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité, a reserve force of the French National Police in charge of riot control) enforce a ‘no fixation’ rule, preventing people from establishing any permanence or stable connection with volunteers, services and local residents. Evictions routinely take place every 48 hours when enforcers harass and push people around, destroying tents and seizing their belongings. In underpasses and public spaces, people make temporary sleeping arrangements in makeshift shelters. Unable to move forward safely or legally, and faced with harassment and eviction while remaining stuck, migrants in Calais are exposed not only to the harsh policing environment but also to the brutalities of abandonment and the structural violence inherent in the politics of bordering.

When we left Calais on a ‘big boat’ – a popular cross-Channel ferry with on-board duty free shopping to ‘keep everyone entertained as you sail’ – I wondered how many were planning or had already embarked on treacherous Channel crossings on small boats during our stay in Calais. Our return journey was rather uneventful, when going through immigration was simply a well-practiced sequence of queuing, passport checking, stamping and onward travel. For us, the border seemed to disappear into the larger urban infrastructure that made things ‘flow.’ Interruptions were seen as anomalies, and even boredom during the crossing was to be avoided for an overall pleasant experience. However, for thousands attempting to cross the same waters each year, the border extended out and hardened offshore, inflicting violence and insecurity on those without proper identification or considered undesirable to the UK government.

Calais’ borderlands serve as a constant reminder that distinct temporalities and subject-specific immobility are maintained for the purpose of producing illegality (Andersson 2014) and normalising politics of rejection. The overlapping processes of identification, surveillance, interrogation and waiting at the border are not therefore just ‘a by-product of state institutions and bureaucracies,’ as Roos Pijpers (2011) reminds us, but possibly tactics of management and integral parts of state control, where irregular bodies are systematically stopped and checked, captured or evicted.

Juan Zhang is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology at the University of Bristol. Her research focuses on transnational cultural politics in and out of China, and Chinese mobilities across different cultural and social spheres. She is the co-ordinator for the MMB Research Challenge ‘Bodies, Things, Capital.’

See our other posts in this series on Calais’ borderlands: ‘Breaching two worlds: seeing through borders in Calais‘ by Bridget Anderson and the video blogpost ‘Notes from a visit to Calais‘ by Nariman Massoumi.