Race, nation and migration – the blog series reframing thinking on movement and racism.

By Nicholas De Genova

The borders of Europe seem to be the site of a protracted crisis. The fires that devastated the scandalously overcrowded Moria detention camp on 9 September 2020 on the Greek island of Lesvos, which summarily displaced upwards of 13,000 migrants and refugees including small children, who were then left abandoned to sleep on roadsides, signal only one of the most dramatic recent flashpoints of an endemically dismal predicament of misery and despair. Notably, whatever the precise circumstances that caused them, the fires arose in a context of draconian yet woefully insufficient sanitary measures associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. On a global scale, the pandemic has thus exposed the inherent contradictions of state power and its (in)capacities to manage the public health emergency. The recourse to curfews, mass quarantines, and more or less severe forms of social ‘shutdown’ or ‘lockdown’ has likewise served to legitimate and bolster a predictably insular governmentality of ‘national’ or ‘European’ quarantine, manifest above all in border closures that only exacerbate the public health crisis by rendering the health and wellbeing of some categories of non-citizens’ bodies expendable, and thereby relegating some human lives to a debased status of disposability.

Since its very implementation in 2015, the EU’s ‘hotspot’ mechanism for migrant and refugee reception and detention has been a very prominent instance of the indefinite coercive immobilization of human mobility. The hotspots’ premier function in practice has been the preemptive rejection and containment of migrants and refugees at the borders, whereby the EU-ropean border regime operationalizes a more or less permanent state of exception. In this respect, therefore, the borders of Europe are not merely the site of an ostensible ‘crisis’ that intrudes upon ‘Europe’ from outside, bringing to its doorstep all the proverbial bad news of the world as embodied in a motley crew of ‘unwanted’ (illegalized) migrants and refugees. No. Instead, the borders of Europe are a means for producing and sustaining a permanent sociopolitical condition of ‘crisis’ that mediates the rejection, illegalization and prospective expulsion of the great majority of migrants and refugees who arrive.

From their very inception, the hotspots by which EU-rope sought to manage the mass influx of migrants and refugees in 2015 were deployed to lend credence to the spectacle of a purported ‘crisis’ that appeared to command ‘emergency’ measures. Yet, even that ‘refugee crisis,’ which was speedily re-branded as the by-now infamous ‘migrant crisis,’ had itself been preceded by one maritime disaster after another, year after year, as overcrowded and unseaworthy boats carrying migrant and refugee border-crossers capsized or were otherwise shipwrecked in the Mediterranean. Indeed, for more than two decades, the persistent fortification of the borders of Europe has made the crossing more perilous and ever more potentially lethal.

The vast majority of migrants and refugees seeking to remake their lives in ‘Europe’ arrive from places formerly colonized by European powers (or in any case, places otherwise deeply implicated in centuries of European imperial projects). Likewise, the vast majority of ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees’ who perish as a consequence of the policing of the borders of ‘Europe’ are people who come to be racialized as non-white and ‘non-European’. When the EU-ropean border regime systematically generates and predictably cultivates the conditions of possibility for the mass death of Black and Brown people, what else can it mean, then, other than that the borders of ‘Europe’ are an apparatus for the postcolonial reconfiguration of a global regime of white supremacy? The borders of Europe thus emerge a premier site for staging the unfinished business and open-ended struggles of our shared postcolonial condition.

This helps to explain why and how the mere term ‘migration’ serves in the European context as a discursive proxy for the antagonisms of race. Official disavowals of the legitimacy of ‘race’ and sanctimonious repudiations of racism undermine a frank confrontation with the historical and contemporary realities of European colonial and postcolonial racism as an ongoing and unresolved affair. This notorious and increasingly futile European evasiveness around questions of race — even as virtually every public debate over ‘migration’, or ‘refugees’ or ‘integration’ is inevitably saturated with racial significance — thus infuses and perverts the very possibility of an honest reckoning with the questions of what ‘Europe’ is or could be in the future, or who is or can be counted as ‘European’. This is the complex that I call the ‘European’ Question.

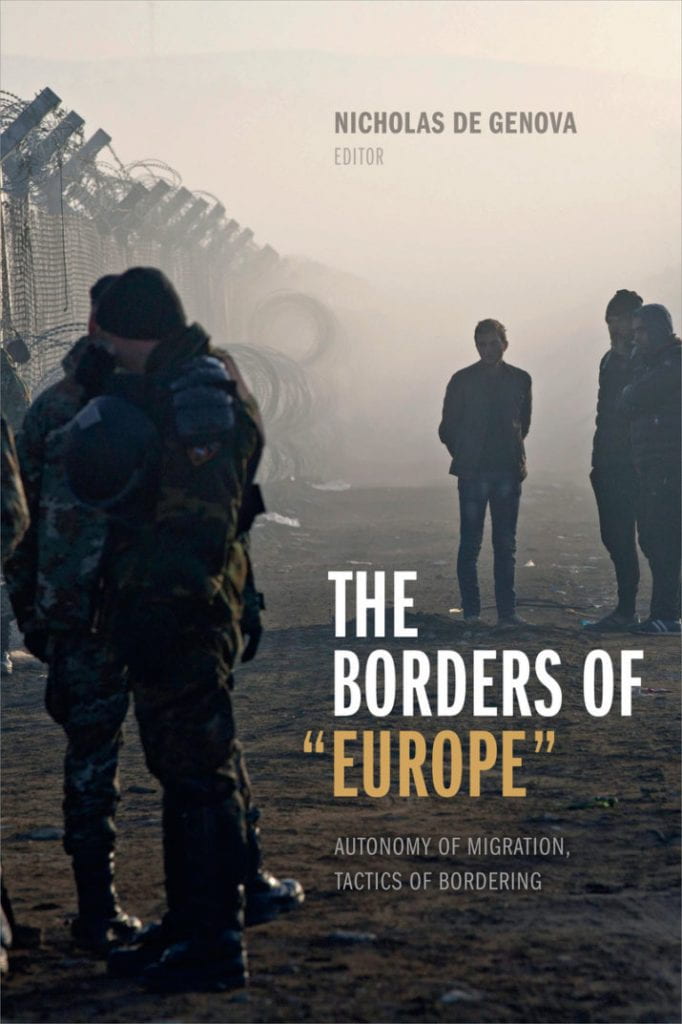

In a book that I edited, The Borders of ‘Europe’: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering (Duke University Press, 2017) the contributing authors and I investigate a variety of examples of the bordering tactics of ‘Europe’ as reaction formations to the elementary human exercise of a freedom of movement that is not granted by any authority. In this manner, we emphasize the primacy of human mobility — what we and other critical scholars call the autonomy of migration — as an incorrigible subjective force enacted in practice, prior to all the tactics and technologies for imposing and policing borders. The research engages various moments leading up to and culminating in the so-called ‘crisis’ of 2015-16, but also excavates a variety of episodes that earlier instigated analogous invocations of a ‘crisis’ at Europe’s borders, which have always tended to signify first and foremost a crisis of control.

As the events of last year verify anew, the European border regime cannot cease to be convulsed by ‘crisis’, because it is a reaction formation dedicated to controlling a force that is elemental and incorrigible within any apparatus of state power. The exercise of our freedom of movement — objectively speaking, in defiance of any border, the police, the law and the state, and even at the risk of our very lives — is an assertion of the primacy of our human needs. In this way, these perennial struggles over human mobility that provoke an effectively permanent ‘crisis’ of the border are expressions, in practice, of a desire and a demand for another way of life. And they gesture, however humbly, toward a horizon where another world is possible.

Nicholas De Genova is Professor and Chair of the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies at the University of Houston. As an anthropologist, geographer and social theorist he studies migration, borders, race, citizenship and labour.

The Borders of ‘Europe’: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering (2017) is available from Duke University Press.