By Ann Singleton

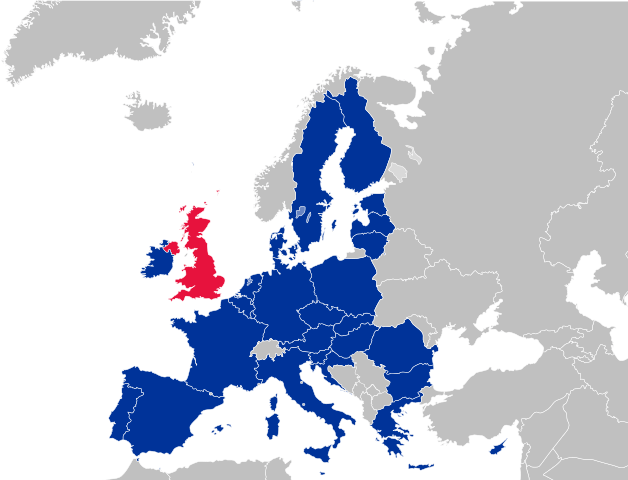

As the UK leaves the European Union, a legislative change will update the EU framework for the collection of migration and asylum statistics. This might receive little attention outside the specialist focus of academics or policy makers, but it is important for anyone with an interest in migration trends, analysis and policy in the UK and in the EU.

Regulation (EU) 2020/851 came into force on 12th July 2020. It is the latest step in consolidating an EU-wide legislative framework for the collection of statistics on migration and asylum. Following Brexit, the UK will no longer be subject to EU legislation in this field. It is most likely to continue participating on a voluntary basis in Eurostat’s migration and asylum data collection system.

This Regulation aims to improve the collection of data on what the European Commission calls ‘managed migration statistics’ (mainly about ‘third-country nationals’). It keeps the same methodological approach as its predecessor, Regulation (EC) No 862/2007, whilst it amends, replaces and updates some definitions and disaggregation requirements. More frequent and timely supply of data to Eurostat is also now required. Other main changes of substance relate to the integration of administrative data (an area that the UK Office for National Statistics has also been working on intensively); financing of actions to strengthen the data collection systems in the Member States; and, perhaps more controversially, under ‘inter-operability’ measures, allowing for the use of data by ‘multiple organisations’.

Better quality and coverage of data is recognised as being essential to produce indicators for measuring the success or otherwise of migration policies. Consistency in the time series would be continued as the amending legislation was intended to enhance and add to the existing provisions in the 2007 Regulation. A core underlying principle of the new legislative proposal is to ensure methodological consistency with that set out in the 2007 Regulation.

The 2020 Regulation also allows for implementing measures and for the financing of pilot studies in the Member States to investigate the feasibility of developing new data collections. The overall picture of ‘demographic migration’ will also be addressed in a forthcoming regulation on European Population Statistics, currently in preparation.

All these changes are timely in an international context, as they coincide with work on the revision of the 1998 UN Recommendations on Statistics of International Migration. These recommendations envisaged an ideal best practice, which in effect has proved to be unachievable in most countries across all categories of information. During 2019 and 2020 the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs has been working on proposals for their revision, with the intention of providing relevant guidance for national activities in the field of migration and asylum data collection. The new recommendations are anticipated to address some of the new realities of human mobility, together with realistic expectations of national capacities for collecting, delivering, analysing and reporting on data.

Will the new EU legislation and the revised UN Recommendations lead to better quality, coverage and comparability of migration data?

The extent to which these measures have an impact on data collection will also depend on the efforts of national authorities and the funding they commit to improving data quality. There is always a compromise between what is deemed necessary and what is achievable in policy terms at national level and EU-wide level. The 2020 Regulation acknowledges demands on data suppliers and the need for consistency by accepting the methodological basis for the collection of data on migration and asylum statistics, whilst amending and extending the scope of the collection and adding additional categories. It is most likely that the UK will be invited to continue providing data to Eurostat, which should ensure continuity in the Europe-wide dataset. Whether this happens will depend on the final terms of the Brexit arrangements and/or willingness to participate on a voluntary basis. It is thought possible that the UK authorities will continue to send Eurostat at least some asylum data and some migration data.

What is missing?

Official data do not capture the changing dynamics of migration and the realities of the lives of people who negotiate their journeys to, within and from Europe in relation to the changing legal boundaries and borders. There remains, uncaptured by the official data, a broad category of legal and irregular migration encompassing a wide range of human mobility. This involves different forms of documentation, legal authorisation and different groups of people. The data gaps can therefore only partially be filled by the 2020 Regulation. Still missing are:

- data on migration and socio-economic variables;

- systematic data collection on ‘saving lives at the border’ (one stated aim of the European Agenda on Migration).

The latter is a glaring omission in the overall picture of EU policy failures. The only systematic global data collection on deaths of migrants at the borders and during migration is the Missing Migrants Project of the IOM. In the era of increased public discussion that Black Lives Matter, it is significant that the UK and the EU still need to address this issue.

Policy implications – monitoring the economic and human costs of ‘managed’ migration

Some significant gaps in official data collection and in public knowledge will continue to limit the possibility of systematic scrutiny of policy in the UK and across the EU. There appears still to be no intention to collect information for public use on what happens following forced returns – that is, what happens to people who have been removed from EU territory. EU Member States should monitor the outcomes of returns as a requirement under EU law (Directive 2008/115/EC), as well as the consequences of their acts or omissions in the return process.

All these gaps also shed light on the need for action to address the racialisation of terms, concepts and definitions used in the measurement and analysis of migration in the context of post-imperial national systems.

Academic and policy actors could take this opportunity to engage in a meaningful dialogue about what is measured, what is known and what is missing from the data, from academic research, policy debates and from public discourse about migration.