By Rebecca Yeo.

On Human Rights Day, 10th December 2021, a mural on the wall of Easton Community Centre was officially opened. It brings together and promotes messages from Deaf, Disabled and asylum-seeking people living in the Bristol area. The collaborative process of creating the mural is the latest in a series of projects facilitated by artist Andrew Bolton and myself, including work in Bolivia and in the UK. In this most recent project in Easton we specifically sought to bring together the Disabled people’s movement and people with experience of the UK immigration system, as well as to develop creative means of engagement during the pandemic.

My research focuses on responses to disability and forced migration in the UK (Yeo, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2021). Within this, I investigate and seek to reduce the barriers separating the asylum sector and the Disabled people’s movement – there is considerable overlap in the experiences of people in both. Many asylum seekers, for example, experience severe mental distress or have other impairments. However, with this mural we were not only working with asylum seekers who identify as Disabled but with a wider section of both groups to build an understanding of the similarities and differences in their experiences.

The mural conveys key messages of the hopes and struggles faced by asylum seekers and Disabled citizens. Some people contributed images and others used words to explain what they wanted the world to understand. Andy, the mural artist, worked with each person to include elements of their ideas or images in the overall design. Some people helped to paint the mural background directly onto the wall. Others painted their contributions onto wooden boards, which were then varnished and fixed to the wall. Alongside the painting, each person was invited to contribute to a short film, explaining their messages in their own words.

This collaborative and creative research approach brought together people whose voices are rarely heard in the mainstream media. The images highlight that the asylum system itself is actively and deliberately disabling, but the mural also makes clear that these injustices are not inevitable. The top of the mural is divided into three rainbows: on the left, a colourful rainbow represents visions for how things could be; in the middle, the rainbow has more muted colours, representing things changing for better, or worse; and on the far right, a grey rainbow represents the worst injustices.

At the start of the first rainbow, a chain of interconnected people provide help and solidarity to each other (left). However, the University of Bristol’s Student Disability and Accessibility Network explained how this chain of support has been made increasingly fragile through underfunding, and how responses to COVID have been pulling it apart.

Together with many other Disabled people, students expressed their relief when, during lockdown, university lectures along with many public events became accessible from home. They hoped that lockdown might increase empathy and commitment to long-term provision for people who need remote access. However, Lizzy Horn, a woman who has been largely housebound for the last 13 years described her frustration when, after the first lockdown, the need for remote access was again sidelined. She contributed this Haiku:

Gaze from my window,

The world moves on once again,

I am left behind.

Meanwhile, people seeking asylum described the disabling effects of government policy. Under the colourful rainbow, a group of people chat happily. But in the centre, under the fading rainbow, one man stands with his backpack after leaving a house (below). On the right, the same man is homeless, crouching in a bush. Without food, shelter or hope for the future, he explained that asylum policy had caused him to ‘lose [his] mind’. A uniformed officer and a suited man stand together ignoring the homeless man. These figures represent immigration officers and politicians as well as those in academia, local government and beyond who collude with the police and government policy rather than risk speaking out against injustice.

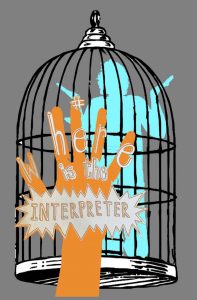

Above this, a series of cages hang from the sky bring together experiences of asylum seekers and Disabled citizens. People from both groups talked about feeling trapped and being unable to move on in their lives. In the first cage (right), under the muted rainbow, a wheelchair user is surrounded by confusing information from social and mainstream media. The socially constructed nature of the cage is highlighted by having a second image of the same wheelchair user under the brightly coloured rainbow, but this time sitting in a comfortable pagoda, able to engage with and contribute to the world (see cage image above).

The middle cage (below) contains a Deaf person with their arms out signing ‘Where?’ In front of the cage there is a hand with the words, ‘Where is the interpreter?’ This image from Lynn Stewart Taylor is the symbol for the campaign that she established in response to government failure to provide British Sign Language interpreters for public health announcements about COVID. As with many images in this mural, the image is also very relevant to a wider population: government announcements about the pandemic have routinely been provided only for English language speakers. The final cage holds a dead canary, evoking the historical practice of taking canaries into mines to warn of gas leaks. This mural warns that urgent action is needed to save lives.

Next to the final cage there is a drawing of Kamil Ahmad, a Disabled asylum seeker who was murdered in Bristol in 2016. The image is repeated from his contribution to a mural in 2012 – it depicts him holding his head in despair at the injustices caused by the Home Office. The mural is dedicated to him, in a quest to build solidarity and prevent further injustices.

The mural enabled participants to claim a space in a public setting and raise awareness of their experiences of marginalisation. The images and messages will also be submitted to the United Nations as part of this year’s shadow report from Deaf and Disabled people. The UN uses this report, alongside an official government submission, to assess how the UK is meeting its obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of Disabled People. This is the first time that the experiences of asylum seekers have been included in the shadow report.

In these ways, this mural is intended not just to convey people’s experiences but also to contribute to change. The key message is that if we work together it is possible to build a better world and extend the colourful rainbow to include everyone. It calls for solidarity between the asylum sector, the Disabled people’s movement and allies – as one contributor put it, ‘togetherness is strength’.