By David Jepson

From the Policy, Politics and Practice blog series

How do public policy interventions come about and how are they delivered? What are the respective roles of researchers and those who design and deliver programmes including politicians, public officials, civic society and the media? I have thought about these questions for decades and there is no better area to explore them than migration.

In recent years, conflict, instability, economic inequality and a natural desire for people to seek better lives has continued to drive migration. The Syrian civil war, the Brexit referendum, post-COVID labour market shortages, conflict in Afghanistan, the crackdown in Hong Kong as well as the current appalling violence in Ukraine are just a few recent examples of events leading to further migration towards the UK. The media has heightened the visibility of this movement, which has in turn generated public policy responses at the national and local level – from both state and NGO sectors – within a pressurised and divisive framework.

In this context journalists produce emotive images of migrants, politicians express strong concern over figures so long as they’re in the headlines, and researchers write articles that are often too focused on methodology, too caveated and too long to be easily useable by policy makers and practitioners. Meanwhile local government and NGO providers deliver schemes that draw on past models in which outcomes can be easily quantified – funders tend to support programmes that can easily be measured. They often rely on a loosely researched evidence base that is supported by previous direct experience and anecdotal information. These drivers of media and politics have tested the policy development framework to the limit and beyond.

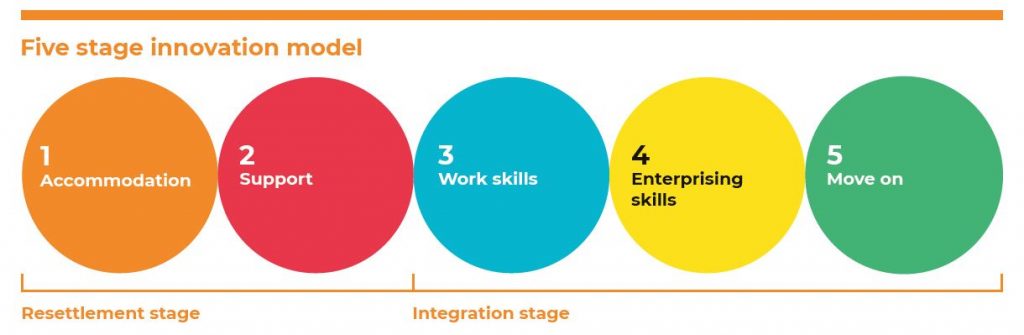

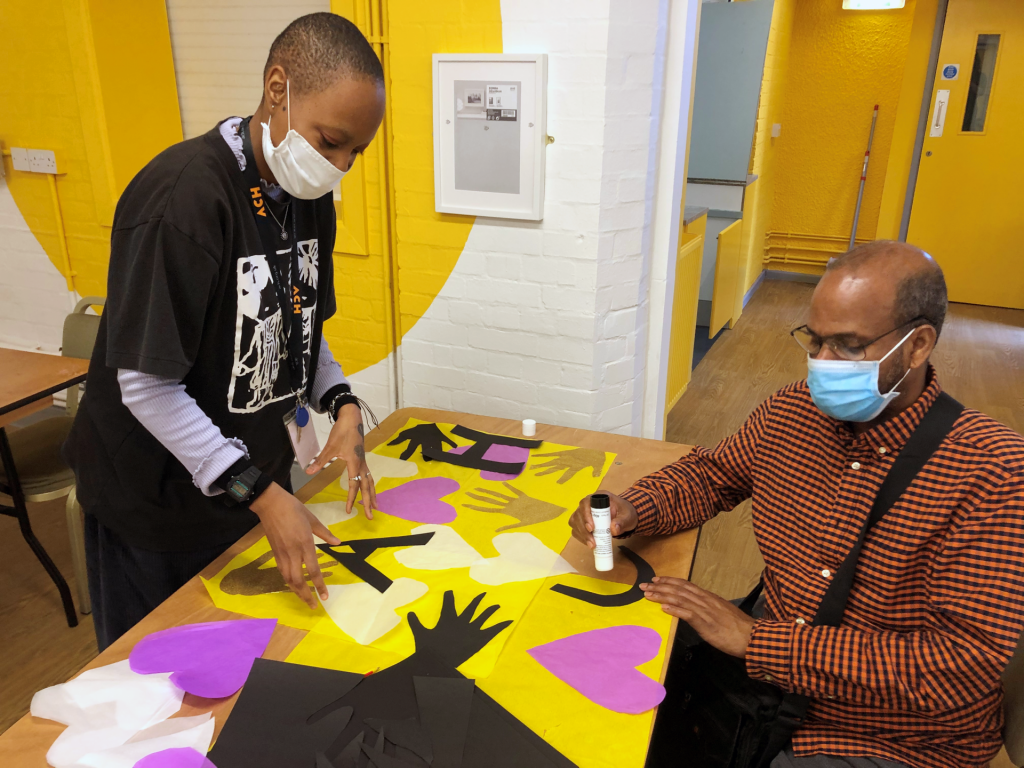

ACH, a social enterprise based in Bristol and the Midlands, takes a different approach by drawing on grassroots experience to inform research and policy development nationally and internationally. We offer resettlement and integration support for refugee and migrant communities through providing housing, careers advice training and support for migrant entrepreneurship. We reject a top-down perspective to ‘integration’ that prioritises assimilation and instead focus on individual aspiration. We work with around 3,000 people a year on the ground in Bristol, Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Coventry. We employ some 80 staff from a wide variety of backgrounds, many with direct lived experience of the migration and refugee system themselves. Our approach is always to deliver support that is tailored to the needs of different communities and individuals.

A specific example is the Migrant Business Support scheme, which aims to directly assist 500 none-EU migrant businesses in the West of England and West Midlands over a two-year period. Funders (in this case the EU) tend to monitor inputs and outputs rather than evaluate longer term impact. Migrant businesses can generate employment, income and social capital for communities otherwise excluded. However, there is often an a priori assumption that it is a good thing for individuals to set up their own business and become entrepreneurs – that it will always generate employment, income and social value for communities that need it. And there is an assumption that support will reduce the risks and enhance the success and social impact of these businesses. But is this the case?

Enterprise and entrepreneurship can certainly create opportunities for some, but such aspirations may also reflect barriers to other employment opportunities, forcing people into small business and self-employment. For businesses that are high risk or offer very low returns it may lead to greater precarity and put people’s housing, access to public services and even migration status in jeopardy. Enterprise ambitions among migrants may also reflect the need for self-employment status as a cost-saving device, bringing all the risks but few of the benefits of entrepreneurship. Of course, different cohorts of migrants have very different situations, which also need to be assessed. For example, the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme, Hong Kong BNO, Afghan citizens and Ukrainian citizens all have diverse demographic characteristics, migration journeys and resettlement pathways. This will affect their means of business development.

The links ACH has developed over the past few years with Migration Mobilities Bristol (MMB) are an attempt to bridge this gap between research, policy development and delivery in order to help deliver business support and other schemes more effectively. For example, we have built an evaluation element into the Migrant Business Support programme led by Ann Singleton, MMB’s Policy Strategic Lead, and Udeni Salmon from the School for Policy Studies, which will generate an evaluation framework to go beyond the usual counting of inputs and outputs.

We have also organised a very successful online seminar series, chaired by MMB Director Bridget Anderson, which regularly attracts more than 60 participants. This has brought together researchers and a range of participants from local government and the community sector in a positive way. Our most recent event in April, for example, explored housing and migration by drawing on the experience of Alex Marsh, an expert on the housing market, Hannah Little from CRISIS, which is doing pioneering work in tackling homelessness, and ACH CEO Fuad Mahamed.

Through MMB we have also been partners in the Everyday Integration project, led by Jon Fox and funded by the ESRC. This research has enabled thinking about precarity, which has reinforced our approach to migrant employment that ensures pathways into long-term and sustainable work. Working with the Big Issue we have jointly initiated action research with the Romanian Roma community in the UK, largely overlooked in narratives about equality. This project will especially focus on vulnerability to No Recourse to Public Funds and how this might be mitigated at the local level.

Finally, we are elaborating a research proposal on Polish and Romanian migrants with Magda Mogilnicka from the School of Sociology, Politics and International Relations, which could have major implications not only for social inclusion but also for the labour market. It raises issues about the relationship between people as economic actors and as citizens drawing on ACH experience and Magda’s previous research.

These are small but important steps to connect up cutting-edge research on migration with the development of policy and delivery of support to promote better lives. This needs to become an iterative and sustainable process beyond the ad hoc, yet valuable, activities we have undertaken so far. This will not only enhance the role of both researchers and practitioners but will also make more effective use of public money and, most importantly, improve the well-being of migrant communities who contribute so much to the city of Bristol.