By Colin Yeo.

As the British empire gradually remodelled itself into a British nation state over the course of the twentieth century, it was inevitable that problems would arise. There was no masterplan or strategy on how to achieve change and successive governments tended to react rather than plan. Nowhere was this more evident than in the process of redefinition of membership of the emerging nation state.

Until as late as 1 January 1983, all citizens of all Commonwealth countries were, according to British law, British subjects. This had been the legal regime at common law, before British subjecthood was put on a partially statutory basis by the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914. It remained the legal regime when the British Nationality Act 1948 became law.

What the 1948 legislation did change was the constitutional nature of British subjecthood. Until then, British subject status derived from a person’s place of birth and a direct relationship of allegiance to the crown. In future the question of who was or was not a British subject would effectively be decided by the legislatures of independent Commonwealth countries. In the United Kingdom and its colonies, the legislature was the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the local citizenship within the Commonwealth was citizenship of the United Kingdom and Colonies.

Both before and after the 1948 legislation, a British subject was free to enter and reside in Britain. At least, that was the legal position. In practice, informal barriers to entry and residence were used to try to interfere with the rights of some racialised subjects. In the case of Bhagwan [1972] AC 60, about alleged illegal entry by British subjects, Lord Diplock held in the House of Lords that a British subject ‘had the right at common law to enter the United Kingdom without let or hindrance when and where he pleased and to remain here as long as he liked.’

This is arguably not quite correct as it was more of a freedom than a right, given that aliens (meaning everyone not a British subject) had historically also been free to enter and live in the United Kingdom. As the legislation of the twentieth century was to show, it was a freedom that could be curtailed for aliens and subjects alike.

The right to enter and reside in a country is one of the fundamental rights of membership of that country, whether labelled subjecthood or citizenship. But the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 removed that right from a wide range of British subjects. The separation of rights of entry and residence from nationality law status was further cemented by legislation in 1968, 1969 and 1971. British subject status was then formally terminated by the British Nationality Act 1981 with effect from 1 January 1983.

This process is not traditionally classed as ‘denaturalisation’, a term usually reserved in modern usage for involuntary loss of formal nationality status on an individualised basis by means of administrative action. On this traditional understanding, denaturalisation is seen as exceptional, albeit to have undergone something of a revival in recent years. Withdrawal of rights of entry and residence from colonial peoples should nevertheless be considered denaturalisation by the central imperial power. With significant caveats, the process was comparable to massive scale denaturalisation by legislative means by certain states in the early to mid-twentieth century.

It might be said that the whole point of independence is to achieve a new citizenship of a new state, which might necessarily involve shrugging off the yoke of the old subjecthood. Such ‘denaturalisation’ might be considered not just consensual but actively sought, rather than imposed involuntarily. But there are two major flaws with asserting that this process was benevolent.

First, the British had hitherto felt free to enter and reside in many countries around the world and in the process repatriated much of the wealth of those countries to Britain and gained a considerable leg up in international trade, in industrial, economic and social infrastructure and more, as Nadine El-Enany argues in (B)ordering Britain. Unilateral withdrawal of access to this bounty quite understandably seemed rather unreasonable to many colonial subjects, who were attracted to live and work in the part of the empire that had overwhelmingly benefited from the imperial project.

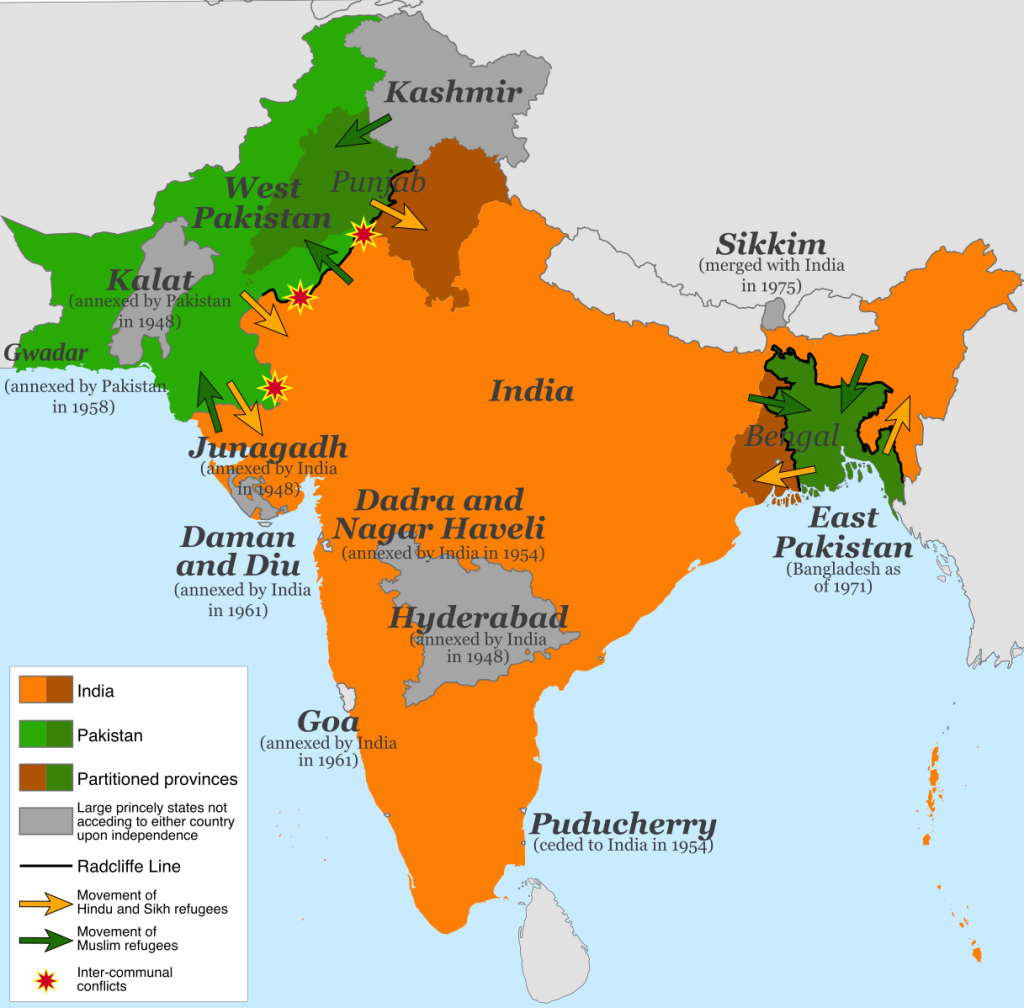

For others, the loss of the right of entry to and residence in Britain was far more than an abstract and as-yet unrealised benefit. Those colonial subjects who had already moved from their original colony of residence to another were routinely denied the right to re-enter or reside — or at least reside with dignity and rights of citizenship — in their new country of residence. The East African Asians are one such group, for example. They were denied the right to live as full and active citizens in their country of residence: some were also denied formal citizenship and some were forcibly expelled.

Many of those British subjects who moved from colonies to the United Kingdom, later dubbed ‘the Windrush generation’, form another such group. It is thought that a very considerable (but unknowable) number were later denied re-entry to the United Kingdom following temporary absences abroad, for example. Others were later excluded from formal British citizenship status by complex and paid-for registration requirements when nationality law was later reformed. Later, some were denied effective citizenship rights by the suite of hostile environment laws brought into force since the late 1980s.

For those affected by these laws this felt a lot like denaturalisation, and with good reason. ‘I don’t feel British. I am British. I’ve been raised here, all I know is Britain,’ Paulette Wilson told journalist Amelia Gentleman in 2017. ‘What the hell can I call myself except British? I’m still angry that I have to prove it. I feel angry that I have to go through this.’ Wilson was not in fact a British citizen according to law, although she was able very belatedly to obtain leave to remain as a foreign national before she died in 2020. This was not before she had been rendered homeless, denied welfare benefits and health care and even detained for deportation at the notorious Yarl’s Wood detention centre. Her situation and her feelings of betrayal and estrangement were very far from unique.

Denaturalisation is not a novel or new phenomenon in British law. The involuntary loss of rights occurring as imperial citizenship was withdrawn first de facto then eventually de jure was a prolonged and, for some, ongoing episode of denaturalisation.

Colin Yeo is a barrister, writer, campaigner and consultant specialising in immigration law. He founded and edits the Free Movement immigration law blog and is an Honorary Researcher at the University of Bristol with MMB. His latest books are Welcome to Britain: Fixing our Broken Immigration System (2020) and Refugee Law (2022). We will be posting a second blogpost by Colin on denaturalisation in the autumn.

Previous MMB blogposts by Colin include ‘The hostile environment confuses unlawful with undocumented, with disastrous consequences.‘ You can also hear Colin discussing the UK Nationality and Borders Bill in an MMB webinar in 2021 here.

If you enjoyed this post you may also be interested in Nandita Sharma’s posts, ‘A tale of two worlds: national borders versus a common planet‘, and ‘National sovereignty and postcolonial racism.’