By Nazia Hussein and Anushka Chaudhuri.

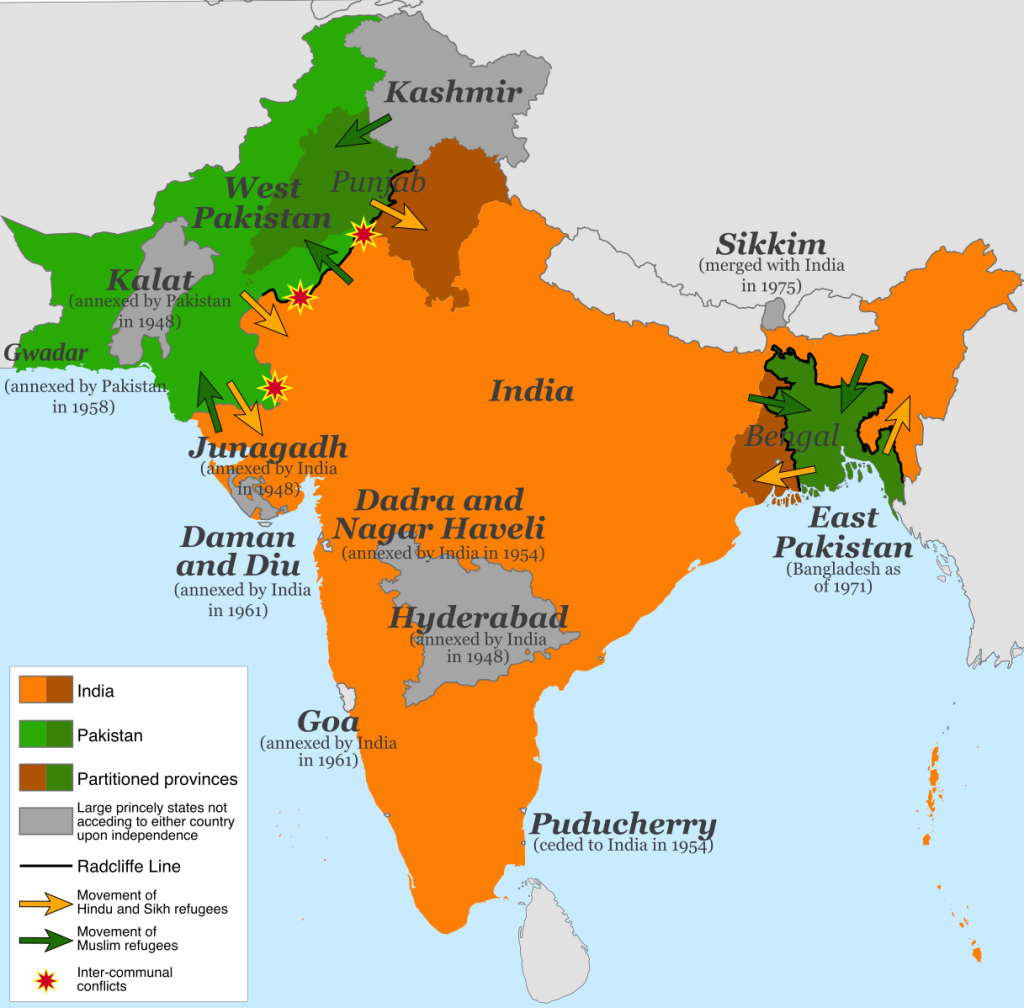

Since its June 2022 release the Disney Plus series Ms Marvel has brought the conversation around the creation of Independent India and Pakistan – commonly dubbed as ‘Partition’ – to the mainstream. The series has been applauded for introducing the first Muslim superheroine and narratives of the Partition – one of the bloodiest episodes in South Asian history – onto global screens, with recognition of the British colonial administration’s active role in its formal withdrawal from, and cleaving of, British India. However, in line with much academic research and popular culture, Ms Marvel presents a partial Partition narrative via the Two Nation Theory. This theory positions Islam (Pakistan) and Hinduism (India) against each other and disregards the violent and multiple partitions of Bengal, which created West Bengal in eastern India and East Bengal in East Pakistan, the latter gaining liberation as Bangladesh in 1971. This positioning is aligned with most popular representations of South Asia and, as a result, erases past and present lived experiences of Bengali Muslims and Bangladeshis.

Created primarily for young and Western audiences, Ms Marvel erases the brutal realities of Partition. The Partition subplot demystifies the story of Aisha, the protagonist Kamaala’s maternal great-grandmother, who secured her family’s safety by ensuring they boarded ‘the last train to Pakistan’ from Punjab, India, to Punjab, Pakistan. The series’ representation of Partition as a time of tension, fear and existential insecurity, but otherwise a relatively organised migration process, amounts to misinformation for global audiences. What ensued after the announcement of the new borders – severing Punjab and Bengal – to create West Pakistan (now Pakistan), India and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) on 14th and 15th August 1947 was overwhelming disarray and disorder. Hindus and Sikhs were to migrate from West and East Pakistan into India, and Muslims were to migrate from India into one of Pakistan’s domains. Violence was widespread. Hence, the minor reference to boarding ‘the last train to Pakistan’ risks erasing the harsh truth that, due to widespread violence, train travel was often inaccessible. The limited number of trains that did run often arrived blood-stained or filled with dead bodies and became known as ‘blood’ or ‘ghost’ trains. Therefore, most individuals migrated on foot or by cattle, with many seeking refuge in camps, being killed or dying from disease.

Many of the academic and popular representations of Partition are heavily Punjab-centric. Ms Marvel follows the same pattern. Its representation not only neglects Bengal’s Partition story but also latently equates the Punjab province with all of Pakistan by symbolically and linguistically portraying, but not directly naming, Punjabi language, culture and lands when representing Pakistani national identity and diasporas. That Bengal was partitioned twice – first in 1905, which, prompted by protests, was annulled in 1911, and then again in 1947 – is disregarded. Such erasures are dangerous, excluding voices from the ‘other half of Partition’ with its differing socio-political histories and ambivalent religious demographics. It also positions a Punjabi Partition narrative in popular culture as representative of this period, when there are other equally complex and alternative histories. For example, upper caste Bengali Hindus (including Zamindars or landowners) dominated political, arts and agrarian labour systems, subordinating Bengali Muslims and other lower caste workers and prohibiting their access to wealth and land. Coupled with Bengal’s Muslims being the marginal majority, this created a more complex task for the British and Indian political elite when drafting religionised borders.

While the shift of nationalism to communalism in Bengal is blamed for Partition, such narratives erase the agency of contemporary Bangladeshis’ and then-East Pakistani populations’ (denied) choice in their fate. This is observed in the political elite District Congress Committee in Sylhet’s pledge to Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement – a Hindu contextualised Indian anti-colonialism movement which emphasised non-violence – despite the Committee’s lack of commitment to this type of struggle. Furthermore, after Hindu Zamindars learned of Sylhet’s lucrative tea estates and the international demand for tea, Muslim-majority Sylhet was fragmented during its 1947 referendum, with some regions being succeeded to greater Assam in India, despite voting patterns revealing an intention for Sylhet to join then-East Pakistan. The agency of East Bengal as a region and a people during Partition in seeking to choose their own destiny – despite being disallowed – is rarely addressed in either academia or popular culture, with Muslims in pre- and post-Partition India continuing to be presented as violent, communalistic and unpatriotic in curricular textbooks and films such as The Viceroy’s House and Earth. The creation of West and East Pakistan itself drew another line between the two regions and populations. This new ‘border’ induced linguistic, cultural and economic oppression, including genocide and weaponised rape, on the Bengalis of East Pakistan. This led to the Liberation War of 1971 when East Bengal again separated from Pakistan, gaining independence as Bangladesh.

The downplaying of the historical struggles of Bengal and contemporary Bangladesh undermines the legacy of discrimination and deprivation experienced by Bengali Muslims and Bangladeshis in the hands of the British colonists, Hindu nationalism and dominance in India, and West Pakistani state and military. This same deprivation is visible in the UK today. British Bangladeshis show the highest rates of poverty and face the largest ethnic pay gap with, on average, 20% less earnings than their white British counterparts. Indians are just 2.42%, Pakistanis 2.58% but Bangladeshis 3.56% more likely to be economically inactive than white ethnic groups in the UK. Further, the death rate involving COVID-19 was highest for Bangladeshis – respectively 5.0 and 4.5 times greater than white British male and female groups in 2020–2021.

In Britain’s classed and racialised surveillance state, Bangladeshis will continue to be labelled and penalised as ‘bad minorities’, likely to experience the worst of the Conservative’s austerity measures, particularly during the worsening cost of living crisis. Such lived experiences of British Bangladeshis reflect a long history of violence, starting with British and European colonialism.