By Melanie Griffiths and Candice Morgan-Glendinning.

‘If you are a British citizen then falling in love with someone who is not British isn’t allowed to happen, basically.’

In the last decade, a series of changes to immigration policy have significantly affected the family lives of people living in and coming to the UK. These have restricted not only the private lives of immigrants but also thousands of British citizens, with implications for their wellbeing, prosperity and sense of national identity.

Shifting policy

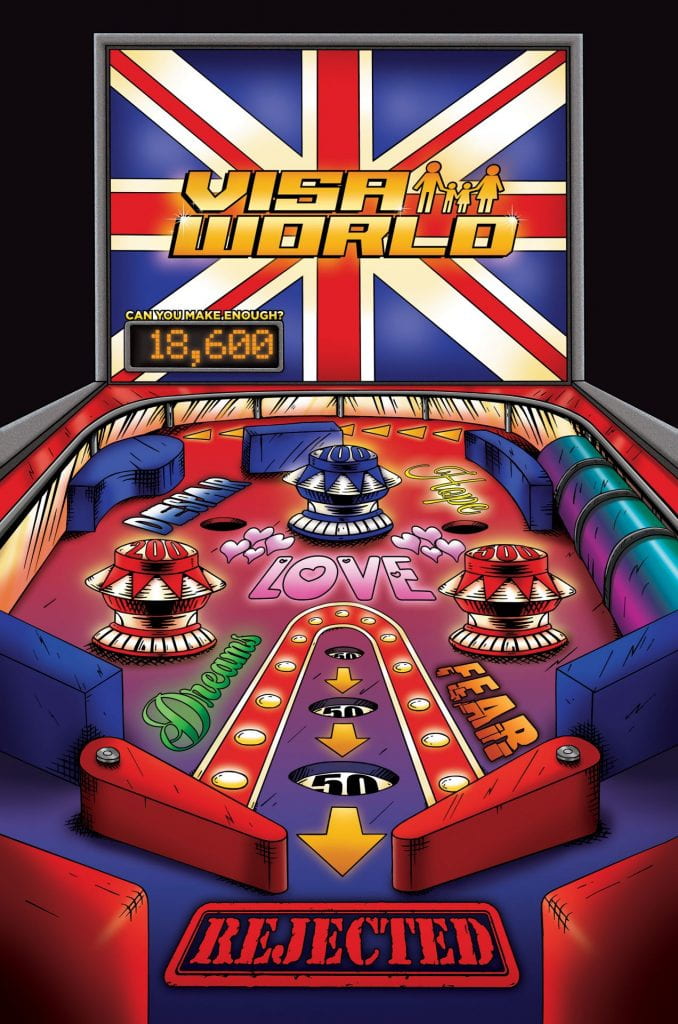

A wide spectrum of changes to family migration rules were introduced in July 2012. This included dramatic increases to the minimum income required by Britons seeking to bring a foreign spouse to the UK, to a figure well above the minimum wage. There were also changes to the entry requirements for family members and lengthened probationary periods, as well as increased – but unevidenced – suspicion over so-called ‘sham marriages’.

As well as affecting the arrival and settlement of foreign family members, concurrent policy changes have curtailed the relationships of people already in the UK. In particular, Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (the right to respect for one’s private and family life) became considered increasingly controversial and suspect. The response has been to make drastic changes to the interpretation of Article 8 and the threshold needing to be met by families, particularly in removal and deportation cases.

Deportability and the family

ESRC-funded research conducted at the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies at the University of Bristol examined the lived impact of these policy changes on mixed-nationality families in the UK. Led by Dr Melanie Griffiths, the project ‘Deportability and the Family’ worked with 30 couples consisting of foreign national men with insecure immigration status and their British partners and/or children. Qualitative research with these couples was combined with policy analysis, observation of deportation and other immigration appeals, and interviews with representatives from the state, NGO and legal sectors.

The couples varied enormously, including in terms of the men’s nationality, ethnicity and immigration status. Some did not have immigration status (for example, by over-staying a visa or entering the UK unlawfully), others had time-limited visas, were in the asylum system, had been refused entry to the UK or were facing removal/deportation. The British citizens ranged from underprivileged to professional home-owners.

Despite the diversity, the families were united by their experience of the immigration system. For the British nationals, in particular, it was a shock to find the Home Office involved in such an intimate part of their lives; questioning, scrutinising and threatening their relationship choices. It was painful discovering that their citizenship does not entail the automatic right to have their families in the UK. As the Immigration Directorate Instructions state, Article 8 ‘does not oblige the UK to accept the choice of a couple as to which country they would prefer to reside.’

This blog post illustrates the lived reality of the immigration and Article 8 policy changes by examining three case studies, showing that despite their different circumstances, British citizens are being directly harmed by immigration rules that they are exempt from.

A deported partner

Aarash (all names are changed) arrived in the UK when he was a teenager and went to school here. But he became unlawfully present when his leave expired. He and his British partner Anna have been together nearly two years and had an Islamic marriage. As a British citizen, Anna assumed that once they married, Aarash would have the right to remain. As they were preparing his immigration application, Aarash was picked up by the police and taken to immigration detention. Both suffered enormously from his detention and the threat of deportation. ‘I just felt like I was losing him, you know. My whole world came crashing down, every single thing, all my happiness.’

Despite Anna’s tenacious fight for her husband’s freedom, the Home Office rejected their human rights claims. Their Islamic marriage was not recognised and the length of their relationship carried little weight. The long, expensive legal fight left Anna exhausted, with huge debts and feeling betrayed by her government.

‘I just looked at all of this and I said, you know what, I’m done. I am not going to keep fighting the UK government. If they don’t want him here I don’t want to be here.’ Anna sold all her possessions to raise enough money to leave the UK to be with Aarash. She did not consider it a choice, but the only way she could be with her husband.

Overseas applications

Emma and her husband James have been together nearly a decade and have two children. James has been in the UK for 15 years; initially on a student visa but later as an overstayer. They assumed that Emma’s good job coupled with their marriage and children would entitle James to be able to regularise his stay but this was far from straightforward.

As a professional, Emma earned enough for a spousal visa, but the Home Office insisted James leave the UK and his family to apply. Although he left voluntarily and paid for his own flight, at the airport James was handcuffed by immigration officers in front of his crying wife and small children and escorted to the plane by officers. The short period of separation they envisaged lasted many months, as his applications were refused, the validity of their relationship questioned, and ever more evidence and money demanded.

Emma was shocked at her family’s treatment, especially the damage that the Home Office was prepared to do to their young British children. They regressed in behaviour and developed attachment problems. Emma could not even comfort them that their daddy would be home soon, because she did not know when, or if, he would be allowed to return.

Time-limited visas

Ivy was teaching abroad when she met Aran and fell in love. They got married and had two children and eventually wanted to return to the UK for the children’s education. But when they began to apply for a spousal visa, Ivy realised that she could not meet the high income threshold whilst working in Aran’s country, where salaries were much lower. They made the decision to return to the UK with Aran on a 6-month visit visa so she could find work to meet the income threshold whilst he looked after their children.

Ivy was lucky enough to find a job quickly in the UK, but she had to work long hours to earn enough for the visa and hardly saw her family. She worried incessantly about losing her job or not earning enough each month.

As Aran’s visit visa came to an end, they faced his having to leave the UK. This was a disaster. Not only for their young children, who would abruptly and indefinitely lose their main caregiver, but for Ivy’s ability to earn enough for the spousal visa. She faced having to quit her job to look after their children, ending her chances of securing a spousal visa. She felt let down by her government and torn between her children’s education and need for their father present.

Citizens betrayed

The British citizens interviewed for this project had wildly different experiences and backgrounds, but all found themselves fighting their own government for autonomy over their family and private lives. They faced harm to their physical and mental health, lost savings, became indebted and were unable to freely decide how to organise their careers and families. All felt that their citizenship was weakened as a result of falling in love with a foreign partner.

The UK’s immigration system routinely questions and dismisses mixed-nationality relationships, pushing citizens into having to choose to live in separate countries, live precarious lives in the UK or leave their country in order to keep their families together, leaving Brits feeling subjugated from their citizenship, judged and unwanted.

Melanie Griffiths is a Birmingham Fellow in the School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham. Candice Morgan-Glendinning is an independent social researcher with a particular interest in immigration, human trafficking and modern slavery policy.

This post was first published by PolicyBristol on 20th July 2021. The report from the ‘Deportability and the Family’ project was launched in June 2021 and can be downloaded from the project webpage along with the PolicyBristol policy briefings and other outputs. You can also watch the webinar launch, chaired by Shami Chakrabati CBE and with speakers including Melanie Griffiths, the NGO Bail for Immigration Detainees, Sonali Naik QC from Garden House Chambers and Ace Ruele, a London-born actor and father who is being threatened with removal.

Melanie and Candice’s previous MMB blogpost ‘Parenting through ‘modern technology’: learning from the pandemic‘ also draws on research in this report and questions the Home Office’s claim that family life can be sustained through virtual means for those separated by UK immigration policies.