By Ravi Jaiswal and Nikita.

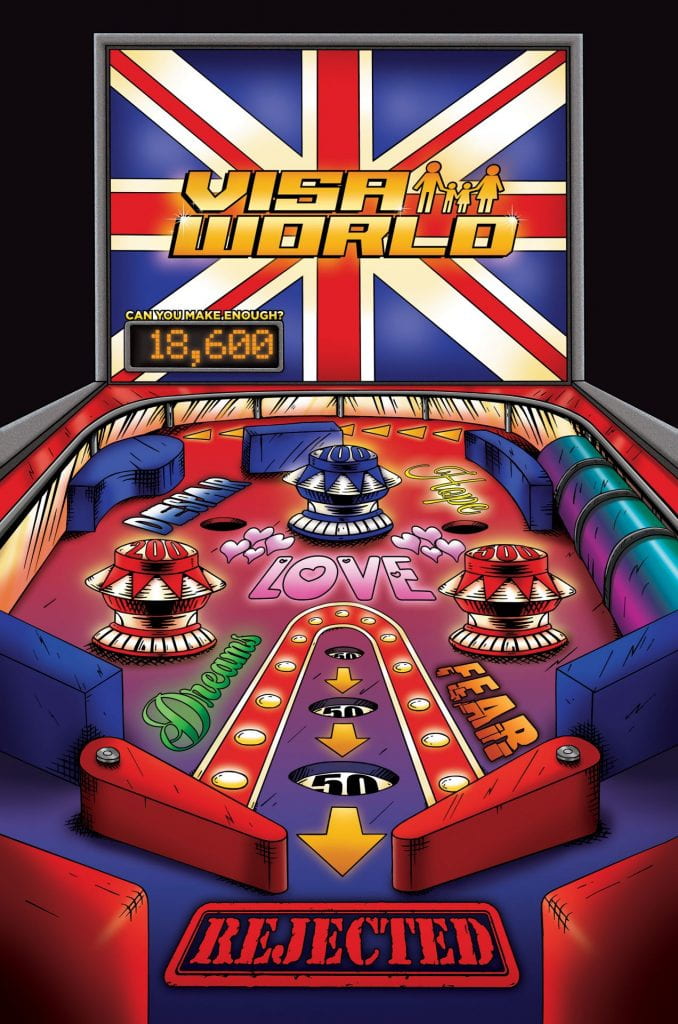

Debates on policy change mainly focus on argument, evidence, and institutional processes. While essential, they can often operate independently and within circles of power. The biases driving decisions and public attitudes shape a dominant narrative in policy demands that diminishes the voices of those affected by the policy. Antigone – International Migrants Day, performed at St Margaret’s House in London, offers a compelling example of how creative practice can intervene at this narrative level, particularly in debates around the rights of migrant domestic workers in the UK.

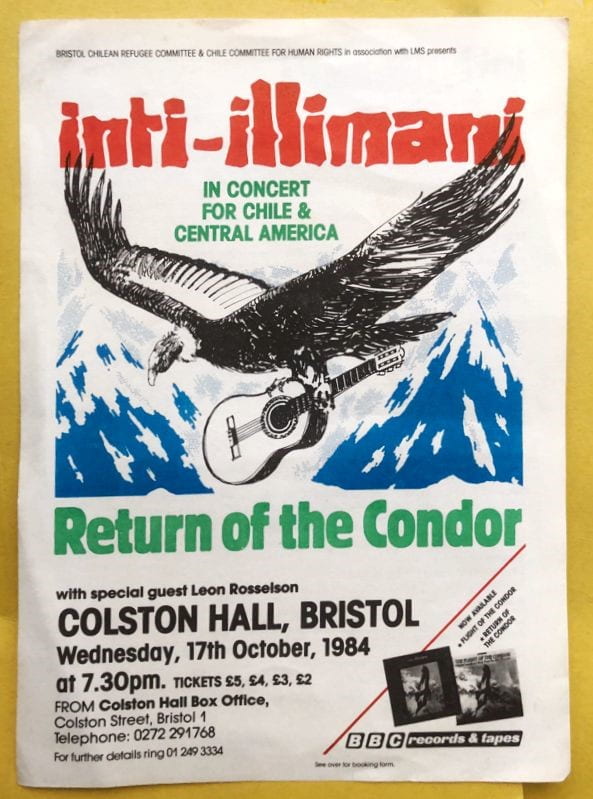

The performance was a part of a creative health and theatre activism project led by Cheryl Gallagher and Drashti Shah, with members of Waling Waling, a migrant domestic workers’ union. This production uses Antigone to engage with contemporary experiences of immigration control, undervalued labour, and resistance. From a governance perspective, the project’s significance lies not simply in its artistic form, but in how it reframes who is speaking, how they are seen, and what political claims become possible.

Photograph by Drashti Shah

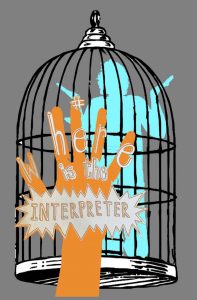

From Victimisation to Agency

Post Theresa May’s abolition of the domestic worker visa in 2012 and the growing hostile environment in the UK, migrant domestic workers were categorised as victims – a narrative trap that focuses on rescuing from abuse over empowering the worker with their rights. Scholar Bridget Anderson constructively critiques the approach of categorising migrants as the good workers or the poor slaves. She argues that the Modern Slavery Act, 2015, essentially stripped away the rights that ensured the dignity of their labour under the domestic worker visa. While this act could benefit workers forced into labour, it fails those who arrived with legitimate work contracts but are still exploited, because their legal right to work has been taken away.

This dominant framing often reduces workers to passive subjects of protection rather than active participants in shaping their own futures. This has concrete implications: their demands for rights, autonomy, and structural reform can be sidelined.

Antigone – International Migrants Day disrupts this. On stage, migrant domestic workers represent themselves. The performance does not ask for sympathy alone, but for recognition of workers as decision-makers, organisers, and political actors. This shift matters because public legitimacy is a prerequisite for policy influence. However, the challenge of mobilising public influence can be a different battle. As Cheryl Gallacher, the Director of the Waling Waling Drama Project, notes, “Our attempt as theatre makers to engage the public, academia, government, and arts and culture organisations has been an intentional process. Our creative engagement is built on the ethos of building agency and respecting the immense campaigning experience Waling Waling brings. Their campaign secured the issuance of the domestic worker visa in 1998. They have lived this struggle and won before. Now, true to its commitment to restoring the visa and including domestic work in the Employment Rights Bill, Waling Waling’s stance has been strong and unwavering.”

Why Narrative Matters in Governance

From a public policy perspective, this project highlights the limits of purely technocratic approaches to change. Evidence can demonstrate harm, but cannot alone change how society values certain lives or forms of labour. Narrative, by contrast, shapes the meaning. It defines how problems are understood and whose perspectives matter.

By adapting a classical story, the performance creates an entry point for audiences who may not be familiar with the realities of migrant domestic work. At the same time, the reinterpretation challenges audiences to question the authority of laws that produce harm. It is deeply political: it asks who laws serve, who they exclude, and what forms of disobedience become necessary when legal frameworks deny dignity.

The Importance of Civic Space

Staging the performance in a community setting – followed by shared food and discussion – transforms theatre into a civic encounter. Audience members are not simply consumers of culture; they are participants in a collective moment of reflection.

This matters because civic space is increasingly constrained, particularly for migrant communities. Such cultural events create informal arenas where political ideas circulate, alliances form, and difficult conversations happen outside formal institutions. These spaces complement policy forums to sustain the social conditions that enable democratic engagement.

Extending this public engagement, the Waling Waling Drama Group performed Antigone for the newly formed Domestic Worker Branch at Unite, the Union. The event garnered huge support from Unite’s leadership, illustrating how changing the narrative can amplify voices within crucial political structures often distracted by competing priorities and the influence of dominant narratives.

Creative Practice as Building Long-Term Policy Infrastructure

It would be a mistake to evaluate Antigone – International Migrants Day solely in terms of immediate policy outcomes. Its contribution lies in changing how migrant domestic workers are seen – by audiences, allies, and potentially policymakers – thus strengthening the foundations for future advocacy.

Dr Manoj Dias-Abey highlighted the difficulty of measuring immediate policy outcomes during the December 16th post-performance panel. At this stage, inclusion in the Employment Rights Bill faces a challenge: the Government prefers to release a broad framework first, deferring specifics to amendments over the next two years. Therefore, a campaign like this, which builds on the groundwork laid since the 1990s and operates on a two-year advocacy timeline, cannot expect swift policy results.

Viviane Abayomi, the outgoing Vice-Chair of Waling Waling, also challenged this drawn-out approach. As she prepares for a long-term campaign battle, she argues that domestic workers’ past victories, including the 1990s campaign that secured the original visa, should be evidence enough for the Government to include domestic work in the Bill now, without requiring another two-year lobbying effort for amendments.

Conclusion

Antigone – International Migrants Day demonstrates that political agency is not only asserted through legislation or lobbying, but also through cultural expression. By reclaiming narrative control and occupying public space, migrant domestic workers are reshaping policy conversations.

For those concerned with migration governance, labour rights, or democratic participation, this project reminds us that policy change begins long before a bill is drafted. It begins with who we listen to, how we understand their stories, and whether we recognise them as political equals.

About the Authors:

Ravi Jaiswal is an alumnus of the MA Governance, Development and Public Policy, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, and currently works at the Brighton and Hove City Council as the Community Safety Caseworker.

Nikita is a PhD candidate in the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science at LSE, where her work focuses on social mobility and social inequalities.