New writing on migration and mobilities – an MMB special series

By Şebnem Eroğlu.

Many people migrate to another country to earn a decent income and to attain a better standard of living. But my recent research shows that across all destinations and generations studied, many migrants from Turkey to European countries are financially worse off than those who stayed at home.

Even if there are some non-monetary benefits of staying in the destination country, such as living in a more orderly environment, this raises fundamental questions. Primarily, why are 79% of the first-generation men who contributed to the growth of Europe by taking on some of the dirtiest, riskiest manual jobs – like working in asbestos processing and sewage canals – still living in income poverty? There is a strong indication that the European labour markets and welfare states are failing migrants and their descendants.

In my recent book, Poverty and International Migration (2022), I examined the poverty status of three generations of migrants from Turkey to multiple European countries, including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands. I compared them with the ‘returnees’ who moved back to Turkey and the ‘stayers’ who have never left the country.

The study covers the period from the early 1960s to the time of their interview (2010-2012), and draws on a sample of 5,980 adults within 1,992 families. The sample was composed of living male ancestors (those who went first were typically men), their children and grandchildren.

For my research, the poverty line was set at 60% of the median disposable household income (adjusted for household size) for every country studied. Those who fall below the country threshold are defined as the income poor.

Data for this research is drawn from the 2000 Families Survey, which I conducted with academics based in the UK, Germany and the Netherlands. The survey generated what is believed to be the world’s largest database on labour migration to Europe through locating the male ancestors who moved to Europe from five high migration regions in Turkey during the guest-worker years of 1960-1974 and their counterparts who did not migrate at the time.

It charts the family members who were living in various European countries up to the fourth generation, and those that stayed behind in Turkey. The period corresponds to a time when labourers from Turkey were invited through bi-lateral agreements between states to contribute to the building of western and northern Europe.

The results presented in my book show that four-fifths (79%) of the first-generation men who came to Europe as guest-workers and ended up settling there lived below an income poverty line, compared with a third (33%) of those that had stayed in the home country. By the third generation, around half (49%) of those living in Europe were still poor, compared with just over a quarter (27%) of those who remained behind.

Migrants from three family generations residing in countries renowned for the generosity of their welfare states were among the most impoverished. Some of the highest poverty rates were observed in Belgium, Sweden and Denmark.

For example, across all three generations of migrants settled in Sweden, 60% were in income poverty despite an employment rate of 61%. This was the highest level of employment observed for migrants in all the countries studied. Migrants in Sweden were also, on average, more educated than those living in other European destinations.

My findings also reveal that while more than a third (37%) of ‘stayers’ from the third generation went on to complete higher education. This applied to less than a quarter (23%) of the third generation migrants spread across European countries.

Returnees did well

Having a university education turned out not to improve the latter’s chances of escaping poverty as much as it did for the family members who had not left home. The ‘returnees’ to Turkey were, on the other hand, found to fare much better than those living in Europe and on a par with, if not better than, the ‘stayers’.

Less than a quarter of first- and third-generation returnees (23% and 24% respectively) experienced income poverty and 43% from the third generation attained a higher education qualification. The money they earned abroad along with their educational qualifications seemed to buy them more economic advantage in Turkey than in the destination country.

The results of the research should not be taken to mean that international migration is economically a bad decision as we still do not know how impoverished these people were prior to migration. First-generation migrants are anecdotally known to be poorer at the time of migration than those who decided not to migrate during guest-worker years, and are likely to have made some economic gains from their move. The returnees’ improved situation does lend support to this.

Nor should the findings lead to the suggestion that if migrants do not earn enough in their new home country, they should go back. Early findings from another piece of research I am currently undertaking suggests that while income poverty considerably reduces migrants’ life satisfaction, there are added non-monetary benefits of migration to a new destination. The exact nature of these benefits remains unknown but it is likely to do, for example, with living in a better organised environment that makes everyday life easier.

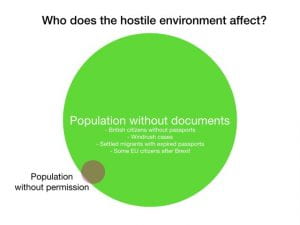

However, we still left with the question of why migrants are being left in such poverty. Coupled with the findings from another recent study demonstrating that more than half of Europeans do not welcome non-EU migrants from economically poorer countries, evidence starts to suggest an undercurrent of systemic racism may be acting as a cause.

If migrants were welcome, one would expect destination countries with far more developed welfare states than Turkey to put in place measures to protect guest workers against the risk of poverty in old age, or prevent their children and grandchildren from falling so far behind their counterparts in Turkey in accessing higher education.

They would not let them settle for lower returns on their educational qualifications in more regulated labour markets. It’s also unlikely we would have observed some of the highest poverty rates in countries with generous welfare states such as Sweden – top ranked for its anti-discrimination legislation, based on equality of opportunity.

Overall, the picture for ‘unwanted’ migrants appears to be rather bleak. Unless major systemic changes are made, substantial improvement to their prospects are unlikely.

Şebnem Eroğlu is a Senior Lecturer in Social Policy at the University of Bristol. Her research focuses on poverty and household livelihoods, and on the economic behaviour, success and integration of migrants. Her recent book, Poverty and International Migration: A Multi-Site and Intergenerational Perspective (2022) is published by Policy Press.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.