By Ryan Lutz.

Praxis for Migrants and Refugees has been advocating for migrant rights in the UK since 1983. It collaborates with numerous researchers and charities to promote more humane immigration policies. Its work often mirrors the debates in migration studies around knowledge production—the what and how of ‘scientific’ knowledge being produced. Decades of Praxis experience have now been condensed into its latest recommended guide, Fair Compensation: A Guide by Experts by Experience, aimed at researchers working with migrants in the UK. The guide offers a roadmap for how to make it more possible for migrants to engage in academic knowledge production about the migrant experience.

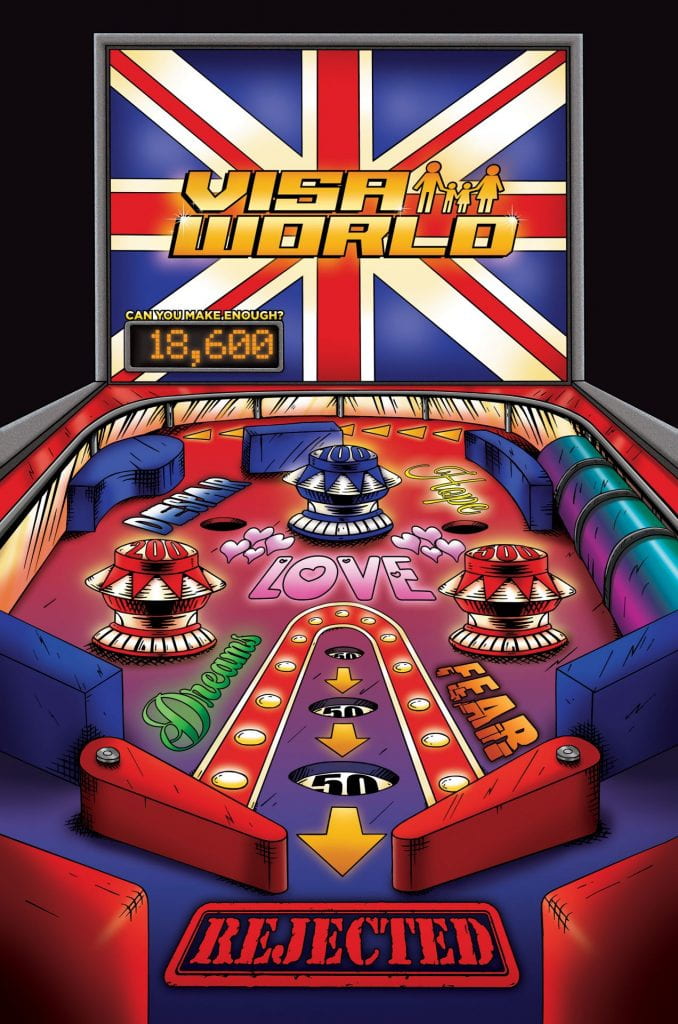

This comes at an important time for migration researchers as migration becomes framed as the one of the foremost political issues both in the UK and abroad. The empirical work we do with migrant communities has immediate political salience, but we are guilty of not focusing enough on making the research process inclusive for the vulnerable populations we write about (Smith and Wool, 2025). One obvious way to do this is by including voices and perspectives from migrants themselves. This infuses a decolonial agenda into our research (Mayblin and Turner, 2020) and ensures the political salience of our work does not sideline or marginalize the communities we do research with and for.

However, like most attempts to make real the transfer of power from migration researchers to migrants, praxis has become co-opted into the newest clickbait term that researchers use for funding and publications (Raghuram and Sondhi, 2023). Some scholars therefore make a point of not engaging directly with migrants in order to avoid the research process being extractive and harmful. But despite these good intentions, academic ‘experts’ making claims about migrant communities rather than with them have, historically, furthered their marginalization (Krause, 2017). It is a delicate balance. Researchers must not avoid engaging with migrant communities for fear of research fatigue or extractivism, but they should also not rush headfirst into working with vulnerable communities before their research process is fully thought through.

The new guide from Praxis is a timely and practical tool for getting this balance right among both established and emerging researchers. Yes, it is true that working with migrant communities can be emotionally challenging and have unintended emotional costs for both researcher and researched. But, thinking of the UK in particular, in an environment where migrants’ right to a dignified life is under consistent and increasing threats, the cost of silence from all of us is too great. This guide on fair compensation, written by migrants, suggests concrete steps for how researchers can support migrants with what they need in order to participate in research.

Participatory research itself rests on a process of respect, mutual learning, reciprocity and personal transformation. By being humble and recognizing where our expertise as researchers ends and that of experts by experience begins, we can unearth truly novel ideas and research findings. When we as researchers value all forms of knowledge—local, experiential and theoretical—we are best placed to truly hear what our experts by experience are saying.

These processes lack a road map and are extremely contextual, which makes them easy to shy away from. But if migrants’ needs are met so that they can reasonably participate in research, the messiness and effort is always worth it. To offer a granular starting point, researchers’ engagement should account for: travel, food, data costs, childcare, reimbursements, event access, clothing and accommodation (if necessary). These are all things the Praxis guide recommends. However, to show how complex this can be, here is a brief story from my own PhD research for which I co-produced a study with migrant communities in Bristol.

I tried to make sure everything I did was fair and commensurate with the migrants I worked with. In many ways, my approach was considered best practice in social science research. I offered meaningful ways to be involved, let their feedback inform my study’s research questions, reimbursed people for expenses and thanked them for their time, incorporated multiple rounds of feedback and involved them in the findings and dissemination of my results (Van Praag, 2021). However, it still fell short in several ways from what Praxis is proposing as the minimum.

Praxis’s recommendations are the new standard for engaging with migrant communities precisely because they come from migrant communities. The authors have worked in research projects and advocacy efforts, and through their knowledge they are telling researchers what we need to consider and build into our future research proposals. Many of these recommendations are along the lines of reimbursement policies.

Offering financial support is just the beginning, though. Each person’s experience is unique so simply asking individuals how they would like to be paid for their time is a human step that gets glazed over in the bureaucracy of research projects. For example, I thought that giving high street vouchers for my participants’ time would work best. But I didn’t account for the barriers they encountered with these vouchers. Whenever I had a co-production meeting I had to spend extra time with each participant to make sure they understood and had successfully redeemed their voucher. University rules prevent us from giving cash directly, which many told me would be more helpful.

When I began my co-production work in Bristol, I thought that by following the guidelines in the academic literature I would glide through the research process. It wasn’t until I stepped out of the ivory tower and into people’s real lives that I realized how much is missed in academic theory and practice. Working with migrant communities is a relational process, and relationships don’t follow a straight line or framework. But taking the time to hear what individuals need—whether it’s paying for childcare, providing reimbursements before an event not after, offering compensation discretely, or having one single point of contact—researchers can truly learn about the migrant experience. And if we learn to look beyond the myriad theories we engage with as academics, we will be able to see how much more fruitful it is to relate to migrant communities not as an ‘other’ or a ‘subject’ but simple as people.