By Katharine Charsley

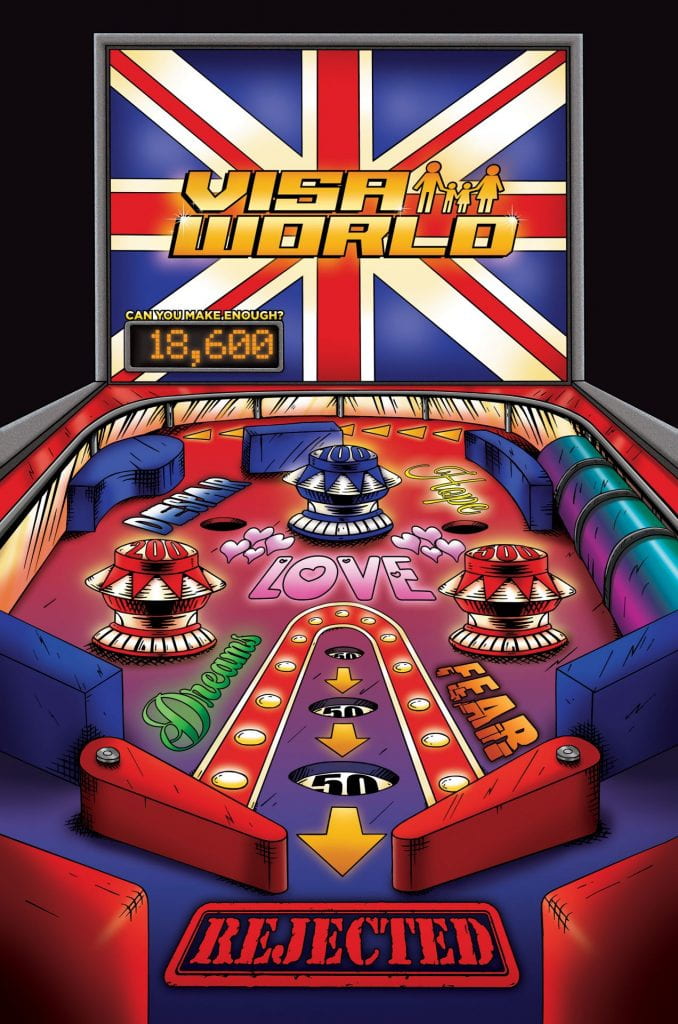

In the wake of the report into the Windrush scandal, in which Commonwealth citizens legally resident in the UK for decades were wrongly treated as irregular migrants and denied basic rights, Secretary of State Priti Patel has announced her intention to work towards a ‘fair, humane, compassionate and outward-looking Home Office’, which treats individuals as ‘people not cases’. There has been no sign, however, that the government is considering changing the UK’s family immigration rules, which routinely separate British citizens and long-term residents from their loved ones. Since 2012, the need to demonstrate earnings above a minimum income (set higher than the pay of around 40% of the UK working population), sky-high visa fees and other costs, an increasingly complex application process, and not infrequent errors in decision making (half of immigration appeals are upheld) have meant tens of thousands of couples and families have been kept apart.

Over the past few months, I have been working with Reunite Families UK (a campaigning and support organisation), other local academics interested in the issue (Helena Wray at the University of Exeter and Emma Agusita at the University of the West of England), and Rissa Mohabir from the specialist organisation Trauma Awareness, on a project exploring the impact of this separation on British people with non-UK partners and/or families. Rissa facilitated a safe listening project bringing together members of Reunite Families UK to talk about their experiences of negotiating the family immigration system and living with immigration-related separation.

Rissa is more used to working with refugees and so was struck by the level of trauma in evidence in the initial project workshop: ‘The depth of feelings and isolation compounded by the prolonged application process, highlighted lesser known trauma responses of the participants.’ As well as the emotional impact of not being able to be with their loved ones, parents grappled with combining long hours of work to meet the minimum income requirements together with enforced single parenthood and children traumatised by the absence of the other parent. The uncertainty of how long separation would last, or indeed whether they would ever be reunited, could be torturous. Many participants described significant tolls on their mental and physical health. When life situations became difficult – through bereavement, health crises or political events overseas necessitating relocation – the inflexibility of the family immigration system compounded difficulties and trauma.

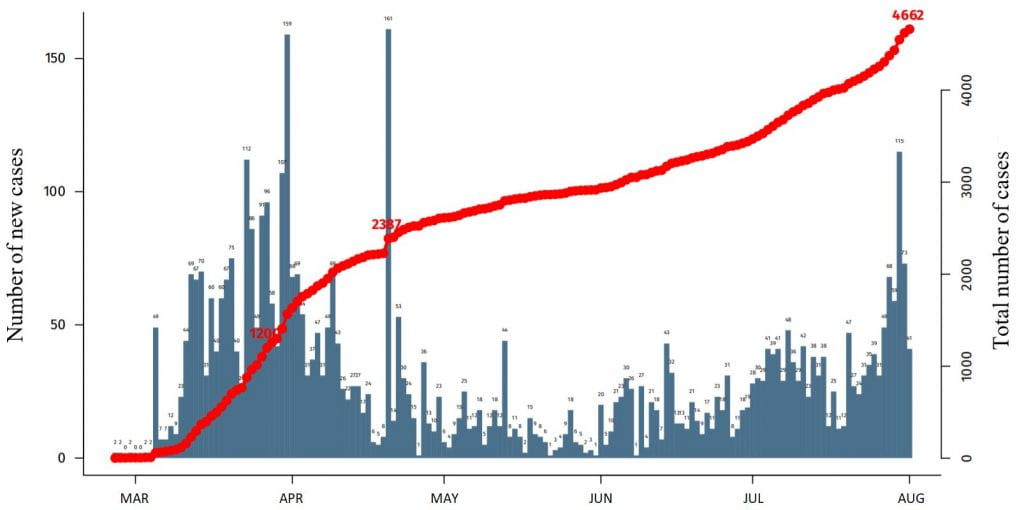

Our work together was interrupted by the COVID-19 crisis, meaning that instead of a second face-to-face workshop the project had to move online. Family separation became an experience shared by many in the UK during lockdown, but for participants still going through the immigration system, coronavirus and lockdown amplified challenges and uncertainties as partners were affected by travel bans. Reunite Families UK members also reported increased anxiety about the impact of lost income and service closures on their prospects of reuniting.

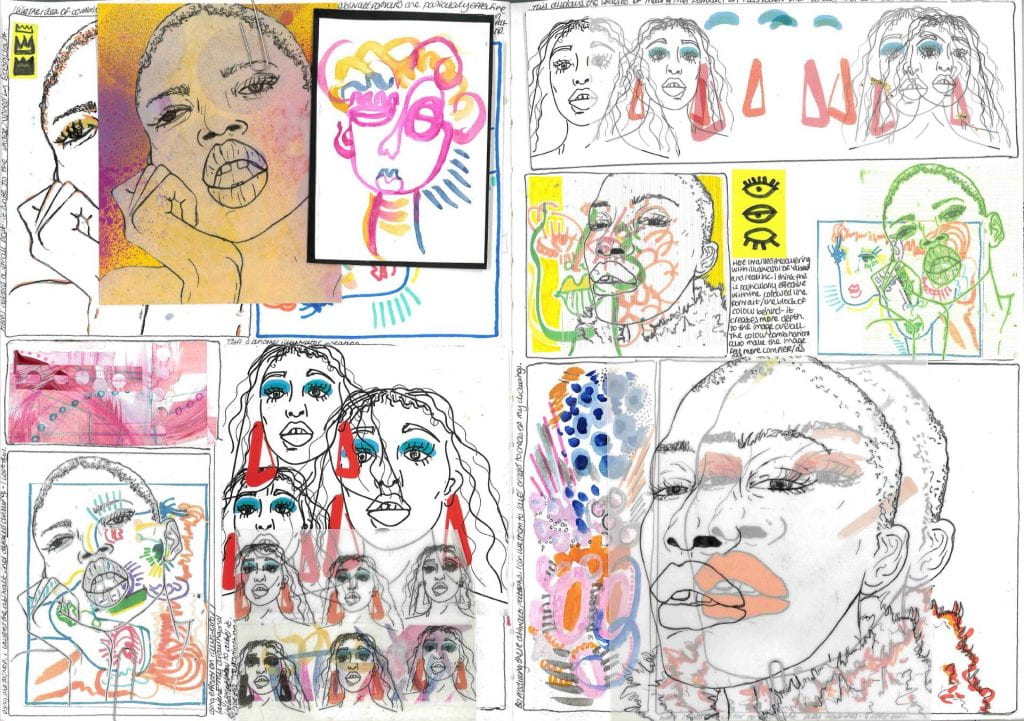

From the outset of the project we envisioned it being a creative process, using a model of co-creating prose-poems (or ‘narrative prose’) developed by Trauma Awareness in previous work with refugee women. Participants in the workshop were asked to bring an object with them which spoke to them about their experiences of separation. In the workshop, describing the relevance of the objects (which included a rejection letter, phones and huggable items to fend off loneliness) became one of several exercises used to elicit words and images, which then formed the basis of our work together.

Rissa and I compiled participants’ words into evocative prose-poems and word art, individual case studies were then added to provide more sustained personal accounts, and we also added information on the family immigration process for those coming to the topic for the first time. An illustrator, Michael Grieve, brought his personal experience of his wife’s visa rejection to developing illustrations for the project. Some were literal – a rejection letter, hugging a pillow in the absence of their partner – whilst others were more metaphorical – the unpredictability and complexity of the immigration process represented by a maze or a Visa World pinball machine (can you make enough to avoid heartbreak and rejection?).

At each stage, we worked with the original participants in a to-and-fro process of co-creation, which saw the results expand from our original vision of a few prose-poems with illustrations, to a full-colour e-book that we hope will both bring the issue to wider attention and provide a resource for those affected by it.

Reunite Families UK launched the book online amid their renewed campaign to scrap the Minimum Income Requirement. An open letter to Boris Johnson has gathered more than 1,000 signatures (add yours here) from affected families, gaining celebrity support from Joanna Lumley and Neville Southall (whose Twitter followers will have found the striking images from the book appearing on their feed this summer!).

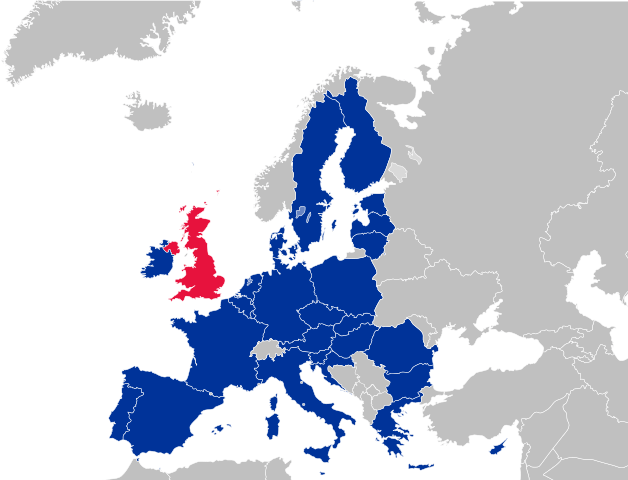

With Parliament just returned from summer recess, Reunite is sending copies of the e-book to MPs. Priti Patel will be getting a printed copy. We hope that she will find time to read it so that the new, more ‘compassionate’ and ‘humane’ Home Office approach will include recognition of the plight of separated bi-national couples and families. With the end of the Brexit transition period looming the alternative is stark: failure to reform the family immigration system will see thousands more separated in future as the immigration rules are extended to UK-EU couples and families seeking the simple right to live together.

View the multimedia e-book here (available as an interactive flipbook, downloadable pdf, or accessible Word document) and a Policy Bristol briefing paper here. You can also read more about the Kept Apart project on the Brigstow Institute website.

Kept Apart: Webinar and Book Launch is being held on 14th September, 6.30-8pm – please register on the Eventbrite page.

With thanks to members of Reunite Families UK, the Kept Apart team (Rissa Mohabir, Caroline Coombs, Paige Ballmi, Helena Wray and Emma Agusita) and Michael Grieve (illustrator), and to the Brigstow Institute (University of Bristol) for funding the project.