By Natalie Brinham.

Eight months after Myanmar’s genocidal violence in 2017, which saw more than a million Rohingyas driven into Bangladesh, 55-year-old Rafique (not his real name) welcomed me into his shelter in a busy section of the refugee camp. He served me tea and asked me to wait – he wanted to show me something important that would explain ‘everything I wanted to know’ about Rohingya statelessness in Myanmar.

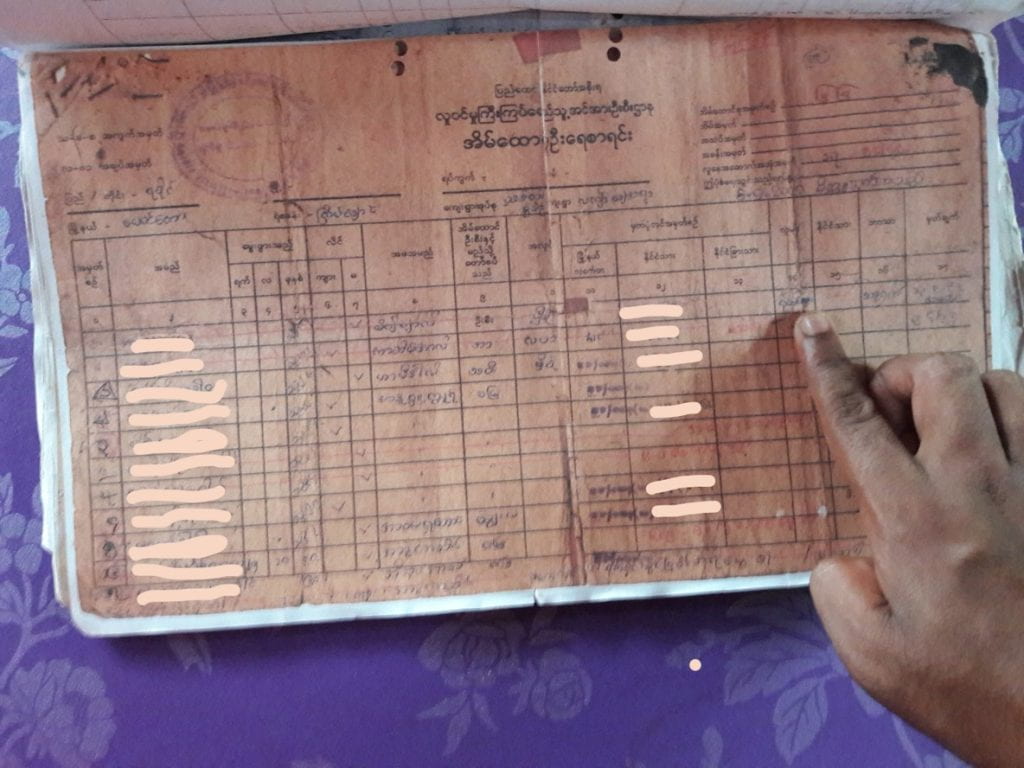

After some time, he emerged from behind the blanket that had been hung as a make-shift wall. He placed a metal cash box on the bamboo floor. Opening it with a key, he revealed a stack of papers, cards and photos – tattered ones, faded ones and plastic covered ones. Very carefully, he unfolded and displayed the contents across the length of the floor in front of me and my young Rohingya ‘fixer’. Methodically, he placed them in date order with the oldest closest to him. There were ID cards from his parents, grandparents, uncles, aunties and children – fraying blue and pink ones from the 1950s, white ones for the 1990s and one new turquoise one; registration documents listing every family member from the 1970s to the 2010s complete with crossings out, alterations and comments added by officials; joint-mugshots of the family holding a board with their registration number; repatriation documents from the 1970s and 1990s; and piles of land registration papers going back to the early years of independence in the 1950s.

‘But Uncle,’ said my fixer in amazement, ‘This must be one of the most complete collections in the whole camp! How on earth did you manage to keep hold of all these documents?’

Other Rohingya refugees had told us how their documents had been confiscated, seized, destroyed and burnt by state officials. Rafique explained how he would wrap the papers and cards in plastic, secure them in a metal box and bury them deep underground. Each year for almost 30 years, he would dig them up, rewrap them and bury them somewhere else. His brother was well connected; when authorities demanded he relinquish old ID cards, he would say they were lost and offered bribes of food, farm produce, favours or money.

Pointing to the documents in turn, Rafique explained – over three hours – how successive regimes in Myanmar had slowly destroyed Rohingya identity as a group belonging to the Rakhine region of the country. He kept the papers, he said, to evidence Rohingya history in Myanmar. He re-told the stories of belonging of his relatives; three mass expulsions and forced repatriations since independence; slow denationalisation; violent encounters with state authorities. Finally, he talked about his determination to resist the current state ID scheme, which ‘makes Rohingya into foreigners’. Group resistance, he reasoned, was intricately connected to the mass violence, killings and expulsions that had landed him in this refugee camp in 2017. Myanmar, he said, would not be a safe place to return to until Rohingyas were ‘given back’ their citizenship.

Invisible people or invisible states?

At a global level, citizenship has been compared to a giant filing system. Each individual human is assigned at least one nationality and filed ‘according to their return address’ or where they can be deported to. From a statist point of view, stateless people – or people without any legal citizenship – are an aberration in that filing system. They have no return address, so cannot be formally deported or expelled.

Human rights advocates take a different view. Those un-filed people are an ‘anomaly’ in an international rights system that is supposed to apply universally to all humans. It’s impossible for people to realise their rights if no state is responsible for protecting or providing for them. As such, stateless people are often described as legally and administratively ‘invisible’. They struggle to access legal protections, education, healthcare, work and financial services. Further, they are unable to benefit from international development and aid interventions.

Though statist concerns over deportability and human rights concerns over rightlessness seem to be ideologically opposed to one another, proposed solutions to the problems of statelessness often align. Administrative invisibility is generally tackled by proposing more state registration, more documentation, more efficiency, more digitisation and more biometrics. Sustainable Development Goal 16.9, which commits to providing a ‘legal identity for all’ by 2030, has become a rallying cry for international development organisations, refugee and migration management agencies, multinational tech companies and NGOs alike.

Yet, these approaches to statelessness by-pass fundamental issues relating to state abuses of power. State authorities consolidate their power through identification technologies and ID schemes, and can misuse these powers to exclude and expel. Few people in the world are actually completely undocumented. More people lack the right documents to be able to live legally in their homes, move freely within their own country, find regulated work or use banking systems. Other people are wrongly documented/registered by state authorities as foreign. The wrong kinds of registration can make things worse.

Despite being hailed as the harbingers of social inclusion, digital ID schemes can harden the boundaries of citizenship, excluding minorities and making it more difficult for people of uncertain citizenship to function in society. As Rafique’s account shows, the implementation of ID systems can be intricately linked to citizenship stripping and mass atrocities. Analysis of how power functions (differently) in particular states and societies, and how it functions through citizenship regimes and ID systems, is absent in ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches to delivering ‘legal identities for all’. ID schemes are often misconceived as neutral processes in which sets of biological and/or biographical facts about individuals are recorded. In fact, they are imbued with power and profoundly impact social relations.

In initiatives to lift ‘stateless people’ out of a state of invisibility – to count them and document them – we fail to look properly at the perpetrating states. States are not identical containers that will function once filled up with international policy recommendations, capacity development and technical advice. Rafique’s oral history, which covered a period of 30 years of UN presence in his homelands, tells a story not of the invisibility of stateless Rohingya, but of how international actors have failed to look at the criminal intent of the state relating to their ID schemes and registration processes.

Statelessness studies often grapple with how to research ‘invisible’ populations. It’s equally important to grapple with how and why state violence has been invisibilised in anti-statelessness work. The very best starting point is to listen properly to survivors of state violence. Rafique’s account is just one of many. Rohingyas and many other stateless people are not really ‘invisible’. It’s just that if we look for them through state-tinted lenses, we tend to look right through the structures that were built to incarcerate them.