By Juan Zhang.

As co-ordinator of the MMB Research Challenge ‘Bodies, Things, Capital’ I have been reading our recent blogs under this theme and am struck by the range and depth of the projects. They cross many contexts, disciplines and research fields, and engage with critical debates around (in)justice, vulnerability, borders and the politics of (im)mobility. From Jo Crow’s personal reflections on the broader implications of economic and social immobility in Argentina through a historical lens to Julia Morris’ poetic account on the damaging politics of ‘value extraction’ through offshore asylum processing in the Republic of Nauru; from Rebecca Yeo’s critiques on the disabling impact of the UK’s immigration control measures to Şebnem Eroğlu’s observation of the long-lasting generational poverty among Turkish migrants in Europe, these blogs provoke thoughtful discussions and raise fundamental questions about the politics of movements through bodies, things and capital. These accounts challenge us to think more critically about the multiple intersections of personal experiences, structural inequalities, infrastructural barriers, historical legacies, and geopolitical shifts on both local and global scales. These reflections and scholarly engagements are central to our research at Migration Mobilities Bristol.

Bodies

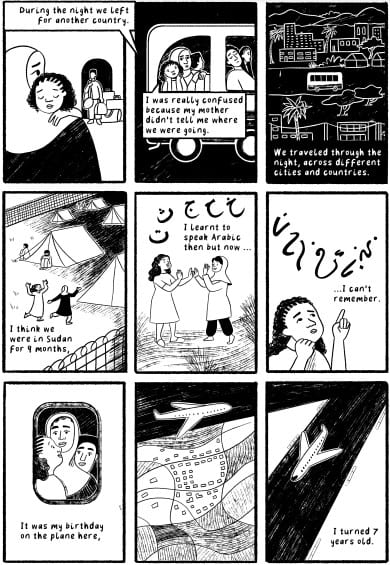

Bodies are intimate sites of encounter – with borders, checkpoints, institutions, infrastructures, policies, biases and discriminatory politics. It is pertinent to recognise the ways in which migrant bodies are intersectionally positioned within and across systems, and this positioning is influenced by various factors including gender, class and race, as well as immigration status (legal or illegal), moral claims (deserving or underserving), and capacities (shaped by disability or other forms of vulnerability). The blogs also prompt us to consider the colonial and contemporary contexts that influence how bodies are perceived and treated.

Julia Morris’ ethnographic work on asylum and extraction, for example, compares the extractive logic in both Nauru’s mineral and asylum processing industries. The colonial legacy of phosphate mining in this island nation finds an uncanny reiteration of a ‘hyper-extractive assemblage’ in modern-day outsourced asylum processing centres, lending particular ‘political, economic and moral values to the global asylum industry’. In this context, the bodies of asylum-seekers become a kind of resource, exploited and commodified in a way not that different from processing phosphate. At the same time, Nauruans themselves are depicted by global media campaigns and refugee activists as ‘savages’ of cruelty, a racialised and stigmatised image rooted in colonial-era stereotypes.

In other blogs under my Research Challenge theme, critical discussions also extend to how migrant bodies are judged based on an (often) arbitrary assessment of ability and the perceived deservability, which influence decisions on vital matters such as access to social services and support, and family reunification in the UK. When bodies encounter policies and perceptions in these intertwined realms, it provides an impetus for urgent scholarly interventions in popular politics, especially at a moment when ‘one in five Britons say that immigration is one of the top issues facing the country’, and the UK’s Rwanda plan continues to stir controversy and deepen socio-political divisions.

Things

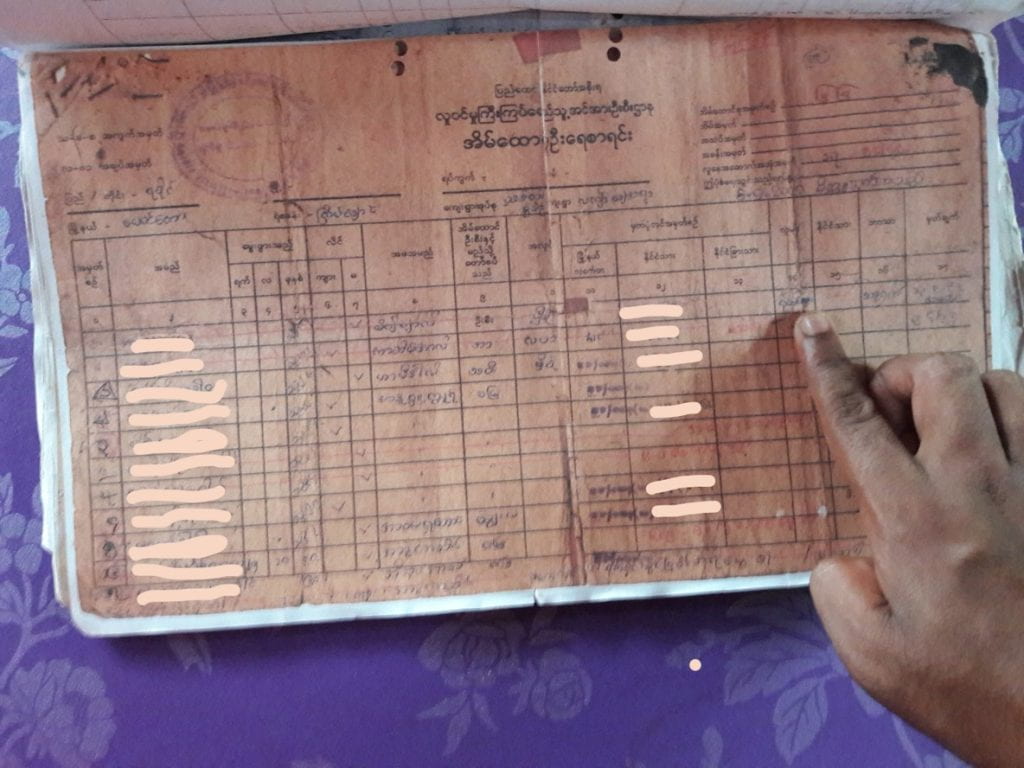

Things offer another analytical engagement with materialities, spatialities and temporalities in migration, through which social relations and identities are shaped and evolved. Things can be objects (for example, passports, visas, maps and tickets) and systems (for example, policies, rules, processing facilities, services), as well as larger transnational bodies (for example, activist groups and NGOs) and infrastructures (for example, media, national services, and cross-national agreements). Things can be physical and metaphorical, and they highlight how movements intersect with broader contexts of trade, exchange and securitisation. Borders are a good example of things – they can be barriers or productive pathways, depending on who (and what) is crossing them. Offshore processing centres in Nauru become de facto maritime borders for Australia, where immigration control is outsourced and externalised. The Jungle in Calais demonstrates another case in point of externalised bordering, where no safe passage is provided by design, in order to deter migrant crossing into the UK. Things such as tents, makeshift dwellings, and temporary shelters are targeted by the French border police to enforce a ‘no fixation’ rule, preventing people on the move from establishing a sense of stable connection to the city and forcing them to move on or go into hiding.

Apart from borders, urban transport infrastructure offers another interesting take on things, where domestic workers in Latin America, predominantly women, struggle with long commuting hours and concerns for discrimination and crime. While public transport allows workers to travel to their employers’ homes, it is woefully inadequate in terms of providing efficient and reliable services or a safe space for female workers to be comfortable with their daily commute. Essential infrastructures such as public transport are things inherently gendered and classed, as they mediate movements and mobilities in highly embodied and differentiated ways.

Capital

Capital emerges as another compelling common thread that brings together reflections on value, differentiation and the infrastructuralisation of ‘extractive politics’ through the control and channelling of local and global flows of humans, resources, knowledge and policy frameworks. It is curious to see how the example of offshore asylum processing in Nauru gains instant ‘political capital’ in the UK, when top decision makers use it as a success model to justify sending asylum seekers to Rwanda as a winning solution. The income-tested immigration rule in the UK also effectively monetises the right to family reunification, turning a universal right into a kind of money game, where the right to bring family to the UK comes with a hefty price tag of £29,000, an income the majority of the working population do not earn. This approach reflects a transactional view on migration, where people are either regarded as assets or liabilities to the capital system, rather than human beings with intrinsic social and familial rights. Even for those who have successfully migrated, like the Turkish migrants in Europe described by Şebnem Eroğlu, structural inequalities and systemic racism create barriers for them to transfer social and cultural capital in meaningful ways, thereby limiting their opportunities to capitalise on these resources for a better life. These cases demonstrate how migration policies and individual lives are impacted by a profound ‘capital logic’, where extractive politics are normalised to maximise accumulation and sideline fundamental ethical considerations.

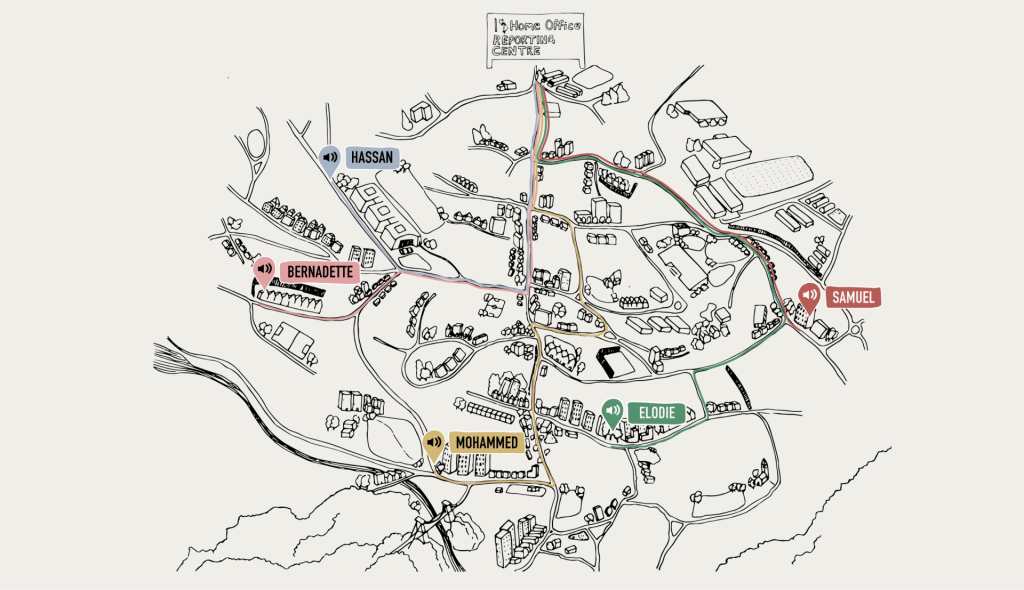

Multimodal methodologies

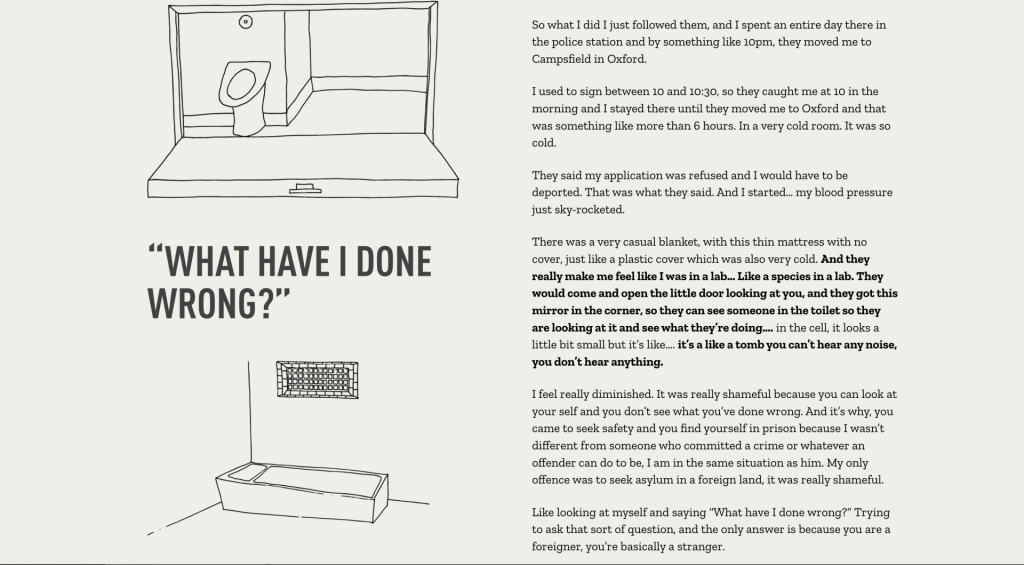

In addition to tracing conceptual connections around bodies, things and capital in these blogs, I have also noted the development of multimodal methodologies, particularly creative and art-based methods focusing on participatory designs and artistic interventions. These approaches have effectively bridged the gap between academic research, public engagement and activism. Other innovative methods, including data visualisation and participant mapping techniques, open up possibilities for experimenting with data collection and analysis. Sylvanna Falcon and her team, for example, use data visualisation techniques to map violence against migrants in Mexico while cautioning against the dehumanisation of migrants who disappear into ‘datasets’. Robledo and Randall’s Invisible Commutes project utilises short audio segments to document experiences of daily commutes by domestic workers, as well as their perspectives on critical mobility infrastructure in the city. The incorporation of migrant voices lends a significant feminist perspective to issues of transport justice.

This Research Challenge has brought diverse researchers and their perspectives and methods together, a kind of assembling of bodies, things and capital in its own right. There is clear potential for developing collaborations and innovating strategies of research practice and intervention in the future, as this Research Challenge brings forward MMB’s commitment to informing academic and public dialogues on migration and mobilities across disciplines and borders.