By Ryan Lutz.

At the MMB postgraduate workshop in July, ‘How Not to Think Like a State,’ visiting scholar Nandita Sharma talked to us about the throughlines of her research. One of these, in particular, gripped me: ‘Anti-immigrant sentiments,’ she said, ‘are used as the basis for fascism.’

I am a migrant PhD student in the UK studying migrant integration and how local-level organisations and the City Council in Bristol resist the draconian policies of the UK government, such as the 2021 Nationality and Borders Bill and 2016 Policing and Crime Act. Despite the government’s policies, the council and local organisations in Bristol are striving to provide a safe and welcoming environment for migrants. The city has a long history of fighting against oppression and racism, including the Bristol Bus Boycotts of 1963, the St Paul’s uprisings of the 1980s, the toppling of the Colston statue in 2020 and the Kill the Bill uprisings of 2021. Additionally, Bristol attracted many migrants from colonised countries during the post-colonial period, meaning there is a history of migrants and ethnic minorities in the city who have been a part of integration services and have successfully built their lives here.

At the beginning of my journey as a PhD student, I thought migrant integration could undercut or potentially combat the use of anti-immigrant sentiment as a vehicle for fascism. Given my lived experience with immigration, nationalism and racism in the United States, I assumed that a lack of exposure led people and the systems they created to be hostile towards outsiders. Through our discussions with Nandita in the postgraduate workshop, my worldview was challenged and complicated in the best possible way.

Historically, integration has been seen as equal access to resources, acquisition of national languages and active participation in society. But this approach rarely asks how migrants experience integration as individuals and fails to question what ‘society’ is and at what spatial or ideological level migrants are integrating. In somewhere like Bristol, where 15% of the population is born outside the UK and 22% self-identify as nonwhite, a wide array of socio-economic realities co-exist. Despite its affluent city centre, Bristol has some of the most deprived neighbourhoods in the country and ranks 341 out of 348 for inequalities experienced by ethnic minorities.

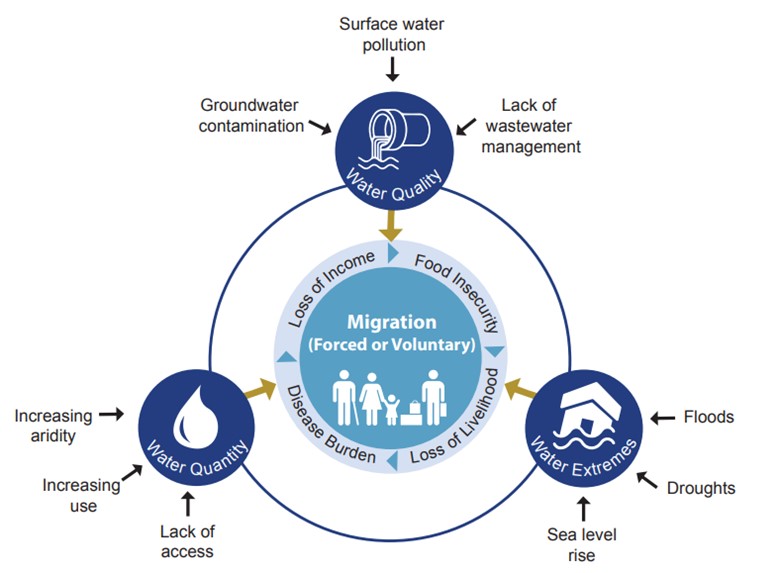

I had always known that integration was a very political issue. Still, through the workshop with Nandita, I began to see how the anti-immigrant rhetoric is now in fact co-opting the integration process in the UK: at a base level, integration plays a crucial role in problematising migrants as others. It situates migrants as apart from the rest of a population, needing to integrate into one unified host society even though, in a country like the UK, there is no single harmonious society to integrate into. The rhetoric that migrants must adapt, integrate and adopt British values places all the blame and burden onto them. And it fails to take into account all of the structural barriers and inequalities they have to navigate daily. Through the increasingly restrictive national immigration policies passed in the UK, integrating becomes more of a pipedream for migrants each year.

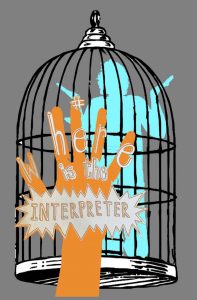

The UK government has been described as an ‘iron rod welfare system‘ when it comes to migrants: they either fall foul of it and are deported or receive legal status and comprehensive social rights. However, the ability to gain that legal status and integrate into a new community has become increasingly circumscribed under the Conservative government – now in power since 2010.

Anti-immigrant sentiments have been an integral part of the fabric of the UK since its inception. In recent decades it has become enshrined in laws such as the 1987 Immigration (Carriers’ Liability) Act, which extended document and border checks to airlines and other carriers, making it their responsibility to keep people out who fell on the wrong side of the iron rod. More recently, the UK government has criminalised seeking asylum from within the UK, awarded more funding to Immigrant Detention Centres and extended the length of time migrants can be held in these centres through the Nationality and Borders Bill. The most recent examples are the Manston migrant centre, which has been described as a zoo by inhabitants, and the firebombing of an immigration processing centre in Dover, which was driven by far-right ideologies. Meanwhile, the Conservative government introduced the Rwanda Plan earlier this year, which has had a host of negative externalities for migrants such as restricting their access to claim asylum, taking away their agency to work or where to live once they are in the system, and making the hostile environment worse.

I wholeheartedly agree with Nandita that, at a national level, the UK completely fits her view of anti-immigration as a base for fascism. But given Bristol’s progressive and radical past, I wanted to believe that there was more than just a harmful system at play. Bristol goes beyond other UK cities with its Refugee and Asylum Seeker Inclusion Strategy, run by the City Council. And there is a robust system of migrant and refugee welfare charities that make up the Bristol Refugee and Asylum Seeker Partnership. These organisations offer services that help to fill the gaps left by the iron rod welfare system of the UK government.

The workshop with Nandita raised many questions about the current Conservative government’s everyday functioning. Namely, as the UK moves further and further towards solidifying its borders and making life as a migrant here a traumatising experience, is the vital work of the migrant organisations in Bristol actually enabling the government’s lack of response? Early research has shown that the government’s anti-immigrant policies increase the workload for charities, which prevents them from campaigning. So now my question is, does this integration work by city-wide collaborations in Bristol help the migrant community? Or are the harmful policies of the national government too much for local welfare systems to overcome?

Overall, the workshop with Nandita was extraordinarily thought-provoking and challenged some of the romantic views I held about the function of government. Most importantly, though, it raised questions about the function of my research as a PhD student and the best path forward for an equitable immigration system.