New writing on migration and mobilities – an MMB special series

By Sarah Kunz.

My new book Expatriate: Following a Migration Category explores the postcolonial history and politics of the category expatriate. It asks what expatriate has been taken to mean in different places and times. How has it been employed and shaped by political and economic projects? Specifically, how has the expatriate been entangled in the mid-century political decolonisation of European colonial empires and the concomitant rise of the USA and the Soviet Union as new world powers? The book looks at what the changing category reveals about how multinational corporations have exerted and defended their power across such geopolitical ruptures, and how they have participated in building a racialised and gendered global economy. It explores how the expatriate has reflected and reproduced social inequality in migration and mobility, not least in access to mobility and its assigned value. Finally, it asks what insights might the history and present of the category expatriate hold for our understanding of the ongoing coloniality of migration and its study?

Expatriate engages such questions as it follows the category through three sites of its articulation. In each of these it explores the situated histories of the category’s making and contestation, and its remaking and lived experience. From these three sites the book also thinks about the politics of migration more broadly.

Choosing sites was not easy – the category expatriate has numerous sites of articulation. This book first follows it to Kenya’s capital, Nairobi. Nairobi is the perfect place to study expats, I was told repeatedly and with emphasis during my research. Nairobi is a young city and from its inception has been a transnational city, a city of migrants. Its creation as an imperial centre and its ongoing role as an economic and political hub have thus been bound up with migrations ranging from the highly privileged to those experiencing various forms of oppression and exploitation. As I learned, the category expatriate has been a central feature of these migration regimes and thus participated in the making of urban space and, indeed, the nation.

The second site I visited was the Expatriate Archive Centre (EAC) in The Hague, an archive dedicated to documenting worldwide expatriate social history. The archive grew out of a project by ‘Shell wives’ to document their lives on the move with Royal Dutch Shell, one of the 20th century’s most powerful multinational corporations. At the EAC I learned about how the expatriate is effective today as a category that helps us make sense of migration histories. I also learned how a foremost multinational corporation has (re)created the racialised and gendered management of its business empire throughout the 20th century through the skilful deployment and interpretation of migration.

The third site of this study is the academic field of international human resource management (IHRM) literature. Recognising knowledge production as a social practice situated within specific socio-political contexts allows studying it as an archive of these social contexts. Approaching IHRM literature as such meant reading it against but also along its grain to reveal the political nature of ostensibly technical writings on labour rotation in multinational corporations. Academic writing emerged as involved in the hierarchical ordering of human movement and labour not least by systematically erasing political conflict and struggle from its accounts and replacing it with cultural explanations.

The book works on the epistemological premise that as categories travel and change, their journeys offer useful analytical gateways to examine broader social changes and shifting power geometries. If migration categories are socially produced, then examining their production is a fruitful research strategy to explore not only the category itself but also the social processes that produced it. Thus, following the expatriate allows investigating both the category and its role in the postcolonial politics of migration and mobility.

Following a category means following the term spatially and historically, textually and in everyday lived experience. It also means following up on its uses and effects and thinking about what might follow: how to move beyond difficult categories and articulate a more just politics of migration.

The book shows the expatriate to be a malleable and mobile category of shifting meaning and changing membership; a contested category, as passionately embraced by some as it is rejected by others; and a sometimes surprising category, doing unexpected work with undetermined outcomes. Yet, throughout its conceptual meanderings and the disputes over its meaning, the expatriate proves consistently central to struggles over inequality, power and social justice.

I found that categories like expatriate, and migrant, are central to the gendered and racialised politics of mobility precisely because of their useful conceptual multiplicity and malleability. However, this also means that the relationship of the category expatriate to racial and gender categories is not given, never automatic and rarely straightforward. Tracing this always shifting and contested relationship is exactly the analytical task.

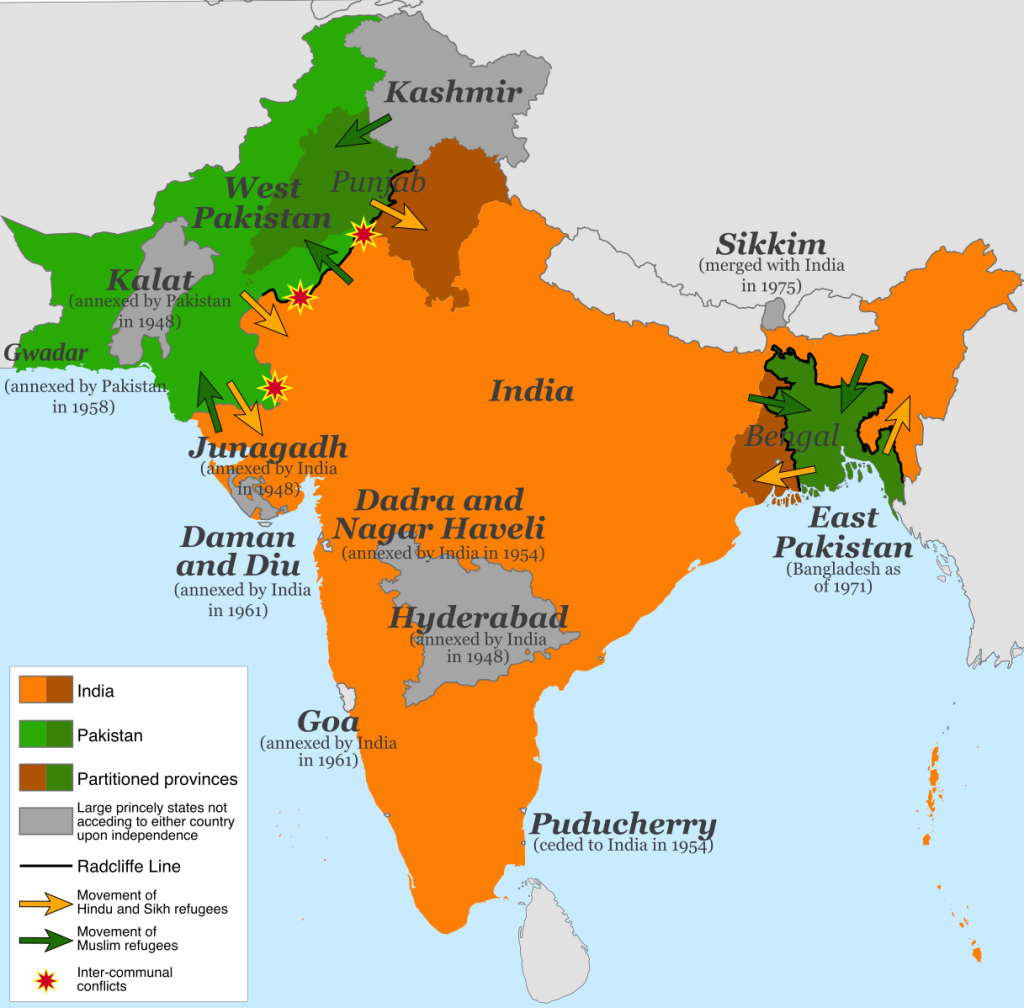

The expatriate has much to teach us about the category migrant, too. Migration is today often equated with the South-North movement of the global poor, and the contemporary migrant habitually positioned as vulnerable and exploited. Many people, of course, do move from the souths of this world to its norths. Many of them struggle, experience violence and exploitation. Yet, if these dimensions come to define the condition of the migrant as such we are creating a homogenised and essentialised figure that risks mystifying socially constituted experiences with specific histories. That which becomes seen as a normal, even natural, part of being a migrant too easily goes unquestioned, even becomes unquestionable. The matter in need of explaining becomes the supposed explanation. Ultimately, this not only limits our understanding of how social inequality is produced, but also limits our ability to imagine and realise a more socially just future.

Further, the migrant as already poor and exploited renders invisible those migrants that in no way struggle but benefit from and advance contemporary power formations, also through their migrations. Imperial state and corporate projects always rely on the migration of their most privileged avatars – and they rely on the framing of these mobilities as altogether different than the mobilities of those who are being scapegoated and criminalised. In this sense, migration categories are core to today’s cognitive legitimisation of an unequally bordered world.

The book thus joins calls for re-orienting our analytical habits from employing categories like expatriate and migrant towards studying them. Attending to categories’ multiply inflected uses and ambiguities, even in scholarship, is instructive. Doing so does not mean determining whether expatriates are migrants and which type thereof, but asking how, in particular instances, they are positioned as different or the same and with what effects and what this allows us (not) to see. In other words, the question becomes what the stakes are of arguments about expatriates (not) being migrants or being a particular type thereof.

Sarah Kunz is a Lecturer at the Department of Sociology, University of Essex, and an Honorary Researcher with MMB. Before joining the University of Essex this year she was a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies at the University of Bristol. Sarah’s research explores privileged migration, the postcolonial politics of migration categories and knowledge production on migration, the historical relationship between mobility and racism, corporate managerial migration, and the commodification of citizenship. Her new book, Expatriate: Following a Migration Category (2023), is published by Manchester University Press.

See also Sarah’s previous MMB blogpost, ‘From imperial sugar to golden passports: the Citizenship Industry’, which explores the rise of ‘investment migration’.