By Sarah Kunz.

In a surprising turn of events, September 2020 saw the end of Malta’s citizenship-by-investment (CBI) programme and its conversion into a residence-by-investment (RBI) scheme. CBI schemes allow the acquisition of citizenship regardless of regular naturalisation criteria, such as residence or language skills, in return for a payment to a government fund or a real estate purchase. Similarly, RBI programmes – or ‘golden visas’ – offer residence permits for money. So-called ‘investment migration’ is among the most significant innovations in recent migration policy and in my research I argue that residence and citizenship-by-investment (RCBI) schemes, and the highly privileged migrations they produce, need to become more central to discussions about migration. Research also needs to overcome nation-state centric frameworks to recognise RCBI as the product of a booming transnational industry: the Citizenship Industry.

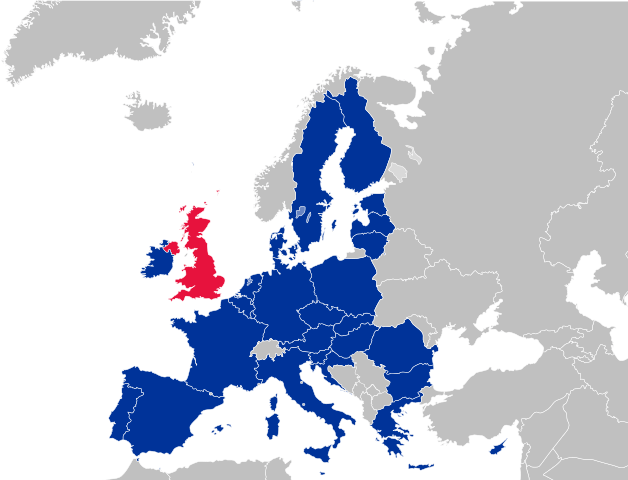

The decision to wind down Malta’s CBI programme came after years of controversy on the island. The programme was criticised not only by the opposition Nationalist Party but also by Malta’s most famous journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia, whose assassination in 2017 sent shockwaves across Europe and eventually caused Prime Minister Joseph Muscat – who launched Malta’s CBI scheme in 2013 and was its staunchest defender – to step down. The decision to phase out Malta’s CBI scheme also – for now – decided the country’s on-going skirmish with the EU, which has opposed CBI schemes for years due to concerns over foreign security, money-laundering, tax evasion and corruption.

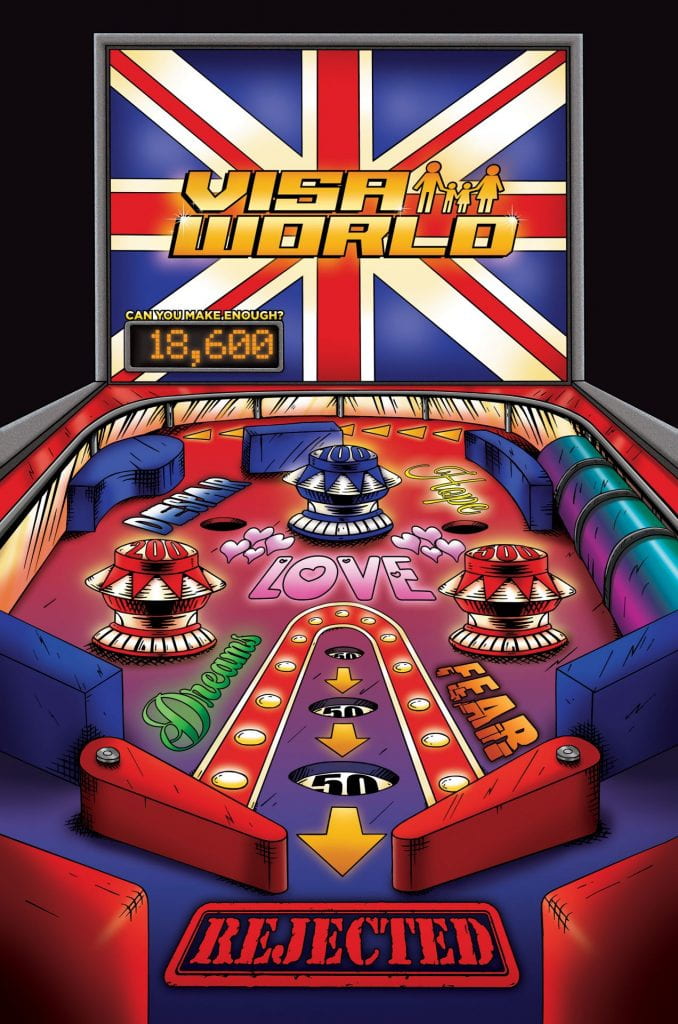

While Cyprus, Malta and Bulgaria are the only EU-members to run CBI programmes, RBI is much more widespread and similarly prone to political controversy. This might be best exemplified by the UK’s Tier 1 ‘Investor Visa’. In 2011, while also rolling out its ‘hostile environment’, Theresa May’s Home office redesigned Britain’s RBI programme to introduce a fast track for the richest among the super-rich and relax residency requirements. Four years later, Transparency International discovered a loophole which meant that between 2008 and 2015 3,000 applicants – the majority from high corruption risk jurisdictions like Russia and China – were granted visas without checks on the source of their wealth or funds.

While European RCBI schemes have been getting more media and scholarly attention, the story of CBI actually began in the Caribbean. Saint Kitts and Nevis has been credited with devising the first CBI programme in 1984 upon gaining independence from Britain in 1983. Yet, as a small and poor island state economically dependent on sugar exports – a relic from its days as the British Empire’s prime sugar plantation – few applicants made use of the provision. This changed in 2006. Its ailing sugar industry had just received a deadly blow from the EU slashing its import price for sugar when the country started working with Henley & Partners, an offshore immigration advisory firm, to develop a new commodity: citizenship. The country’s revamped CBI programme offered ‘citizenship customers’ limited disclosure of financial information, no taxes on income or capital gains, and, from 2009, visa-free travel to the Schengen area. It became a great success.

Crucially, the story of RCBI involves a cast of corporate actors who design, run and promote RCBI schemes – what I call the Citizenship Industry. After working with St. Kitts and Nevis, Henley & Partners helped other Caribbean governments to develop CBI programmes, making the Eastern Caribbean as famous for its citizenship as the Western Caribbean is for offshore financial services. The firm then advised Cyprus and helped design Malta’s CBI legislation, effectively bringing the Caribbean CBI model to Europe. In many ways, the Caribbean has been a laboratory for new models of political belonging that are fast having a global impact. Corporations have been key to this development: effectively creating, skilfully expanding and arguably dominating the global citizenship market. Since its relatively recent origins, investment migration has developed into a USD 3 billion global industry and thousands of service providers now stretch in a ‘golden visa belt’ from East Asia across the Middle East to Europe. Yet, the emergence, shape and role of the Citizenship Industry remains poorly understood and under-theorised.

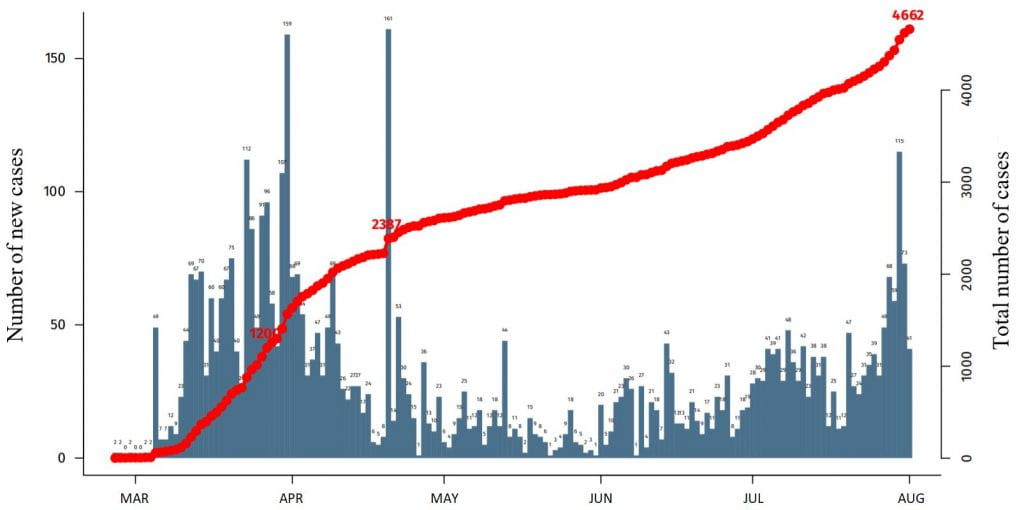

The rise of RCBI programmes has not only been marked by political controversy. It has also raised some fundamental questions about the fairness of selling citizenship and its broader socio-economic and political impact. Advocates of RCBI argue that it brings much-needed economic activity, human capital gains, and substantial government revenue to small economies. RCBI is said to have enabled countries to diversify their economies and better respond to catastrophes, including global financial crises, hurricanes, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Critics, like Shachar (2018), raise troubling questions about how RCBI advances the encroachment of market forces into the political arena and warn that the commodification of citizenship will impact the institution of citizenship as such. This is an especially pertinent point as the sale of citizenship seems to also hasten the institutionalisation of citizenship revocation, as exemplified by Cyprus’s 2020 laws.

There is also on-going debate about the impact of RCBI on social inequality. Here, Shachar (2018:4) finds ‘the hollowing out of the “status, rights, and identity” components of citizenship’ and Džankic (2014:402), notes that investor programmes ‘infringe upon the liberal ideas of democracy’ and allow wealth and social class to disrupt equality of membership. Kochenov (2014:27-29) – who co-published a ‘Quality of Nationality Index’ with Henley’s chairman and acted as founding chairman of the citizenship industry’s main trade association and lobbying body, the Investment Migration Council (IMC 2014), for several years – defends RCBI, arguing that it allows individuals to overcome the inherent unfairness of international border regimes that limit the movement and life chances of many based solely on the randomness of their birth country. Citizenship, then, not only works to enact equality within states but is also, as Shachar (2009) and Boatcă (2016:15) argue, ‘a core mechanism for the maintenance of global inequalities’ and, moreover, ‘the basis on which the reproduction of these inequalities is being enacted in the postcolonial present’.

Whatever our assessment of investment migration, the phenomenon seems here to stay for now. While Malta’s liaison with CBI might have ended, RBI has become a standard feature of many states’ visa offerings and countries as diverse as Jordan, Moldova, Montenegro, Slovenia, Turkey and Vanuatu have either implemented CBI or plan to do so. There is an urgent need to better understand this trend and to explore the growing role corporate actors play in shaping the organisation and meaning of investment migration. Additionally, we need to make sense of this arguably exceptional ‘liberalisation’ of citizenship in the context of the broader ‘restrictive turn’ (Shachar 2018) in migration policy and its associated proliferation of borders, the preventable deaths of thousands at those borders, and the surge of right-wing populism all over the world.

Dr Sarah Kunz is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol. Her research focuses on privileged migration, the politics of migration categories, and the relationship between mobility, coloniality and racism. In her current project, she looks at investment migration with a focus on the Citizenship Industry.

This post was updated on 09/10/23.

Please share this blog post: