By Evelyn Miller.

I am a first-year sociology student at the University of Bristol, and a mixed South Asian woman, my mum being of Malaysian and Mauritian descent and my dad being of English and Irish descent. This blog sketches out the troubles I have experienced in white-majority educational institutions to show why it’s important for university staff and students and to challenge practices that reproduce structures of elitism, whiteness, and masculinity

Before secondary school, I lived in Woking on a diverse council estate with lots of friends and similar families nearby. As I started secondary school, we moved to Godalming, an almost entirely white and middle-class area in Surrey. Our house is on a road that was originally wholly council owned. Set in the Surrey hills, it is not your typical council estate, but a stigma is still attached to living there. Meanwhile, being one of the only families of colour in the town has made us hyper-visible. We are positioned as ‘other’ and our presence is often met with racism and hostility. I remember other children shouting, ‘go back home!’ at my younger sister, aged 10 at the time, as she walked the dog in the first few months of living there. At school and college, I experienced more subtle and institutional racism. There, I did not simply study for my GCSEs and A Levels but was also forced to learn about the inequalities and hierarchies of race and class that positioned me as an ‘other’.

At my state school, I was one of a small minority of people of colour. Even though I often academically outperformed my peers, it seemed I constantly had to prove my ability, while my peers who presented as outwardly middle-class and white were simply assumed to be able. Disappointed by a curriculum that did not reflect my own experiences as a woman of colour, I took it upon myself to bring my views and experiences into my work. For instance, when a small group of us were tasked with writing a satirical article for an AS Level in Creative Writing, I wrote about my frustration at my teachers consistently calling me Moli (another South Asian girl in the year) rather than Evelyn. I titled the article ‘The difference is written all over our faces’, but it met with ridicule from both my Creative Writing peers and my teacher, who even joked about calling me Moli in the feedback. I think the only person who made me feel ‘seen’ at school after reading this was Moli herself.

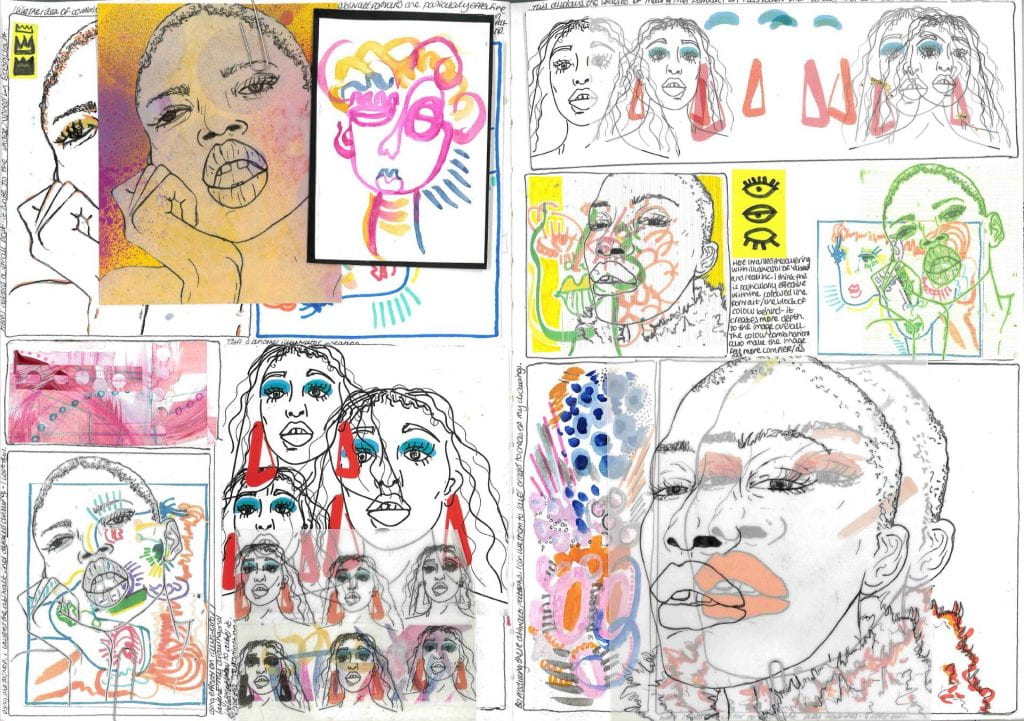

The painful invalidation of my voice and experience continued as I studied for A Levels. My final Art project explored the identities of women of colour through a series of portraits. By sharing this project beyond college, I met lots of other artists of colour, took part in exhibitions, and founded a South Asian collective and magazine, Juice. Yet my art teacher dismissed the project entirely, suggesting I should just focus on portraiture and my artistic technique. Though disheartened, I ignored him and dedicated my Personal Essay and final piece to discussing the representation and agency of women of colour in the art world. I achieved an A*. Though my teacher praised my work, he never acknowledged the importance of the themes I was exploring.

Nirmal Puwar’s book Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place with its analysis of the dynamics of in/visibility experienced by people of colour in white-majority institutions captures my experience at school and college in Godalming. I hoped that in moving to Bristol to study sociology I would leave behind my sense of being a space invader. But I was disappointed to find the core modules offered to first year students still prioritise the theories and thought of white sociologists, especially white men, and often completely overlook the critical work of scholars and activists of colour who had inspired my interest in sociology. In some cases, all the essential readings were by white authors. How can I, or any women of colour, find our place as sociologists whilst being taught that thinking sociologically is almost exclusively a thought process of white men?

Postcolonial feminist thought was introduced, but in a module on global sociology, as if such thinking is only relevant to global issues. Nonetheless, it was refreshing and exciting to study the works of women of colour, although ironically my seminar tutor misgendered the sociologist Gurminder Bhambra, referring to her using the pronouns he/him. Other seminar tutors have been key to my happiness and success this year, however. They have provided me with support and additional readings prioritising intersectional thought, and they have given me hope that we can create radical anti-racist and feminist spaces within the university.

When people of colour question the overwhelming whiteness of British universities, Sara Ahmed says, they are often heard as speaking about themselves, being too ‘subjective’, rather than speaking about wider structures of inequality. But the sociological imagination, as famously defined by C. Wright Mills, demands ‘the vivid awareness of the relationship between personal experience and the wider society’ – personal troubles are inherently public issues. My ‘personal troubles’ described above connect to a public problem, namely the fact that schools, colleges and universities are not ‘neutral’ spaces of learning but continue to take whiteness as the norm and reproduce classed, raced and gendered hierarchies, marginalising minority groups.

Anti-racism activists and scholars have worked for centuries, and continue to work, both within and outside of institutions, to challenge racist systems, policies and practices. Gurminder Bhambra recently presented a radical argument for decolonising universities, the ‘home of the coloniser, in the heart of establishment’, including greater attention to anti-racist practice within universities. It is important for students as well as staff to get involved in MMB’s Anti-Racist Network so that we can collectively explore what it means to decolonise the university and how to do it, as well as wider issues of racism and how to combat them.

Evelyn Miller is studying a BA in Sociology at the University of Bristol. She is a co-founder and the creative director of Juice, an online platform for sharing the lived experience of the South Asian diaspora.

Please contact Julia O’Connell Davidson if you would like more information about MMB’s Anti-Racist Network.