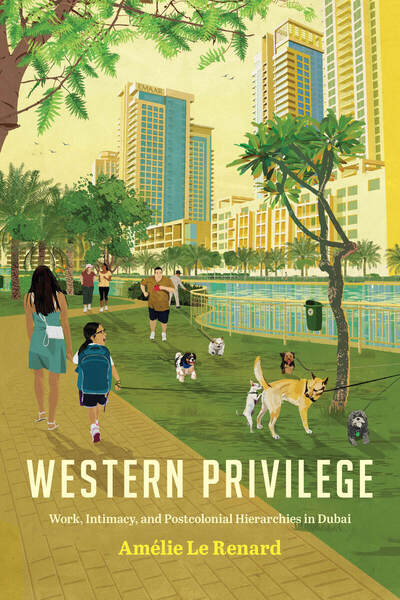

New writing on migration and mobilities – an MMB special series

By Jo Crow.

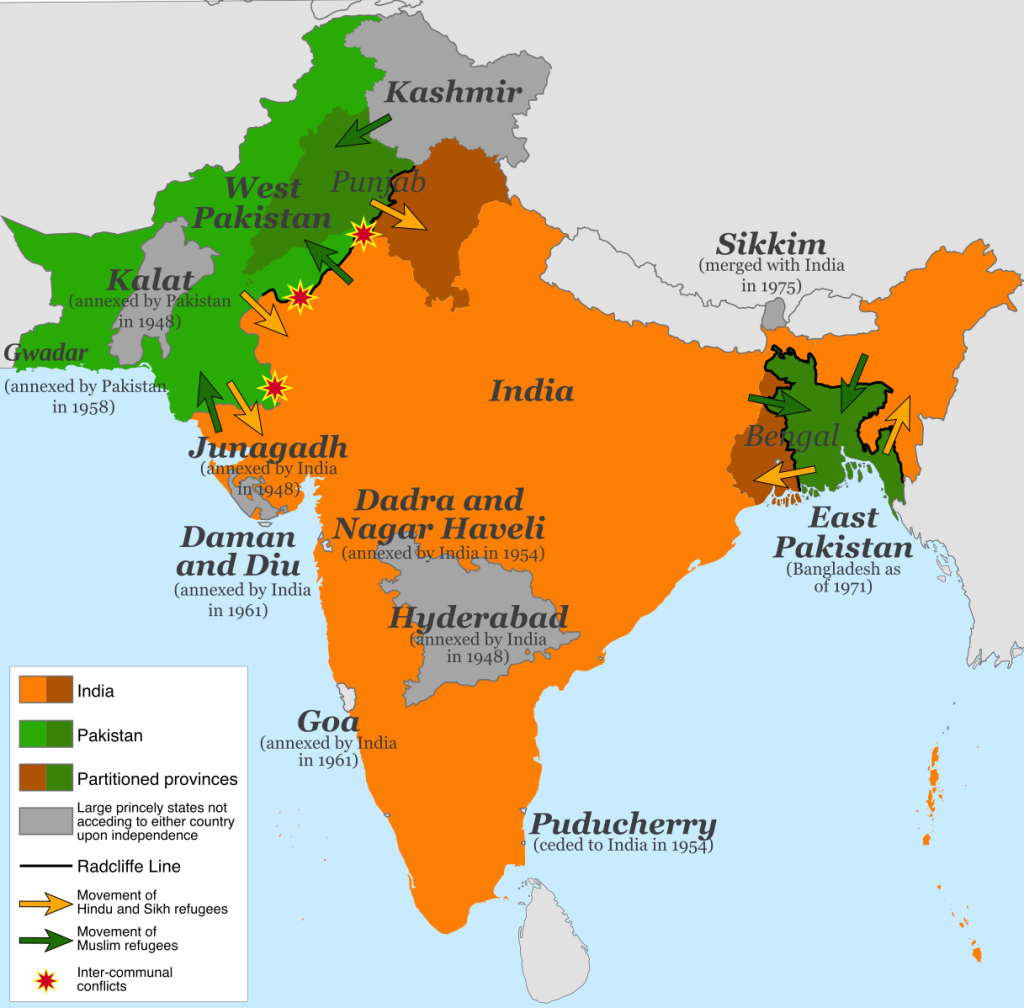

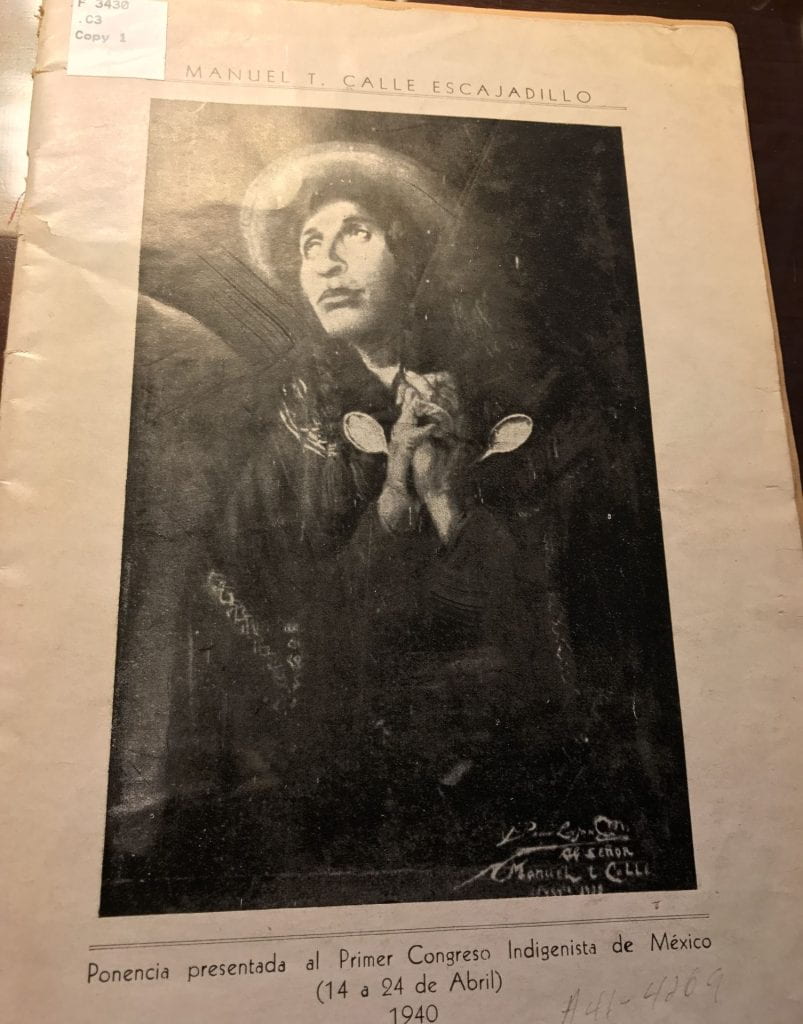

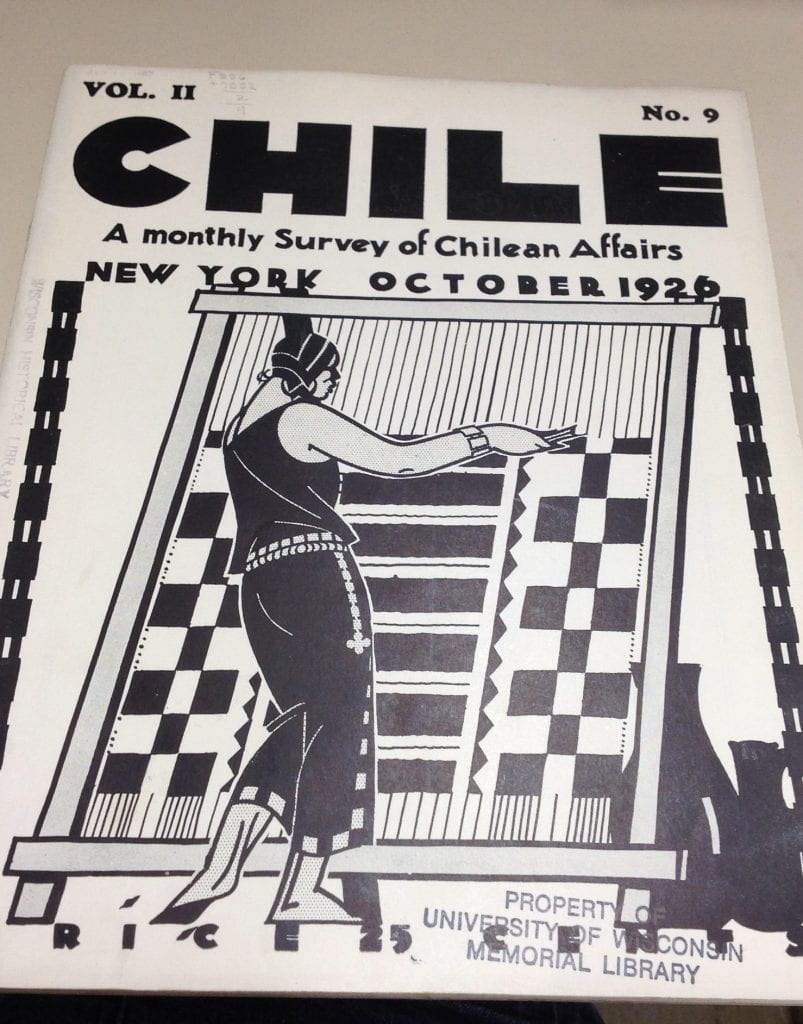

My recent book Itinerant Ideas (2022) explores the multiple meanings and languages of indigeneity (Merlan, 2009) circulating across borders in early twentieth-century Latin America. It takes readers through an extensive visual and written representational repertoire to show how ideas about indigenous peoples evolved as they moved between nations during this period. These representations include newspaper articles lamenting indigenous people’s supposed culture of backwardness, ignorance and poverty, public speeches making indigeneity synonymous with colonial exploitation and subjugation, and reprinted paintings depicting indigenous people as suppliant victims. By contrast, I also reflect on conference proceedings that cast ‘the Indian’ as the epitome of hard work and resilience in the modern world, magazine covers celebrating indigenous cultural creativity and entrepreneurship, teaching materials asserting indigenous society’s intimate and superior knowledge of the land, and poems making indigeneity symbolic of (anti-colonial, anti-capitalist) resistance and rebellion. (See examples of archival documents explored in Itinerant Ideas in the images below).

Building on the work of James Clifford (1997), my book argues that such diverse, contesting meanings and languages can, to some extent, be joined up with either a story of ‘roots’ (the static, ‘local’ Indian, fixed in the rural community, working the land according to traditional custom, antagonistic to the existence of the modern state) or ‘routes’ (the changing, strategising, productive Indian moving in various circuits, central to the success of the modern state).

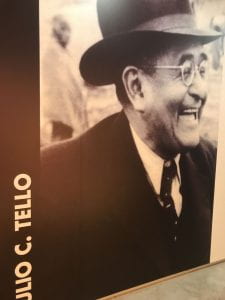

Sometimes the indigenous protagonists of Itinerant Ideas come to represent both stories at the same time. This is the case of Quechua-speaking Peruvian archaeologist Julio Tello (1880-1947) who, before becoming famous in national scientific circles, studied at Harvard and travelled to many European cities, including London, where he attended the International Congress of Americanists and met his soon-to-be English wife. Tello used his national and international platform to celebrate the ‘deeply rooted genealogical tree’ to which he belonged. Such profound roots, he said, ‘extracted from this land the sap which nourished a race of giants’ (speech published in El Comercio, Lima, 14 December 1924).

Ideas about indigenous identity and history matter because they inform state legislation (related to land ownership, for example, or education or health) which impacts indigenous lives. And individuals matter because they develop and disseminate ideas and create state policy. They are bound by state and bigger socioeconomic structures but they are also part of these structures and thereby influence them.

Writing on indigenous conflict in Bolivia, Andrew Canessa (2018) makes the obvious but important point that ‘“indigenous” is not an indigenous concept’ (p.11). While many of the most prominent intellectuals and political activists under scrutiny in Itinerant Ideas were not indigenous themselves a key aim of the book is to emphasise indigenous interventions in debates about indigenous identity and history, showing the many different ways in which they both perpetuated dominant discourses of race and fundamentally undermined and challenged them.

The book also draws attention to the transnational dimension of conversations about indigeneity. In contrast to much of the historiography on race in Latin America, including my own earlier work (Crow 2013), Itinerant Ideas goes beyond the national confines of debates about indigenous rights. This does not mean it is written without nations in mind but rather that it ‘simultaneously pays attention to what lives against, between and through them’ (Saunier, 2013). Transnational debates help us to make better sense of national developments because they feed into and are in turn shaped by them.

The debates analysed in Itinerant Ideas take place through a vast web of transnational intellectual networks. This web is what makes an idea catch on and spread. Individuals invent ideas, which evolve as they are passed on through their networks. The book is therefore as much about relationships as it is about individuals. As Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler have commented in Connected (2011, p.xi), the ‘key to understanding people is understanding the ties between them’.

The book foregrounds indigenous voices within this web. A growing body of literature explores how indigenous social movements in Latin America today are linked into transnational networks. Excellent works also exist on indigenous border-crossing during the colonial era. Much less attention has been paid to the period in between. Itinerant Ideas demonstrates that transnational indigenous organising was a visible and audible reality in the early twentieth century, and that it took many different forms including labour protest, conference attendance, teacher exchanges, missionary activity, art exhibitions and theatre groups.

In order to anchor this investigation of transnational networks, my book looks at one particular cross-border relationship: that of Chile and Peru. The front cover shows a photograph of the Atacama Desert in northern Chile – territory that was Peruvian before Chile annexed it during the War of the Pacific (1879-1883).

Most scholarship on Chile and Peru concentrates on the history of this military conflict and its legacies. This means that relations between the two countries are interpreted almost exclusively as antagonistic and hostile. Itinerant Ideas does not deny the history of conflict but insists that there is another history that is worth researching and telling too – a history of collaboration and dialogue.

As well as Chile and Peru being read as countries always at war with each other, they are also read as oppositional nation-imagining projects. We see, for instance, how Chile has often been depicted as ‘more European’ or ‘less indigenous’ than Peru. The image on the front cover of Itinerant Ideas – an Inca road running through the Atacama Desert – suggests the possibility of a different narrative. It points to a history that brings Chile and Peru together rather than driving them apart. Many of the intellectuals in the book spoke of or wrote an Inca history that covered both these countries. For them, the so-called ‘indigenous question’ of the early twentieth century was something that crossed contemporary borders and moved between Chile and Peru as well as other Latin American countries.

All ideas are always, continuously itinerant. This is born out both in the histories told in Itinerant Ideas and in the travels that the book itself has been on since publication. Due to generous invitations from colleagues in Berlin, Dallas, Oxford, Santiago and Temuco, I have been able to talk about Itinerant Ideas with many different audiences. Our discussions sometimes took us back to key conversations, moments or people in the book. More often than not, though, they took us in new directions, opening up questions – for example, about the global south framework, Latin America’s relationship with the Caribbean, and the global production of indigeneity today – that I am now keen to explore further.

Jo Crow is Professor of Latin American Studies at the University of Bristol and, from January 2024, will be MMB’s Research Development Associate Director. Her research interests include Chilean cultural history, nationalism and nation building, Mapuche cultural and political activism, and the production and circulation of ideas about race in Latin America. Her recent book, Itinerant Ideas (2022), is published by Palgrave Macmillan, with a 20% discount available here.

For more writing on movement and mobilities in Latin America visit our MMB Latin America blog. Posts on Chile include ‘The limits of interculturality: migration and cultural challenges in Chile‘ by Simón Palominos, ‘Mobility and identity in the Patagonian Archipelago‘ by Paul Merchant and ‘Migration, racism and the pandemic in Chile’s mass media‘ by Carolina Ramírez.