By Bridget Anderson

As we cross a temporal border – seeing out the old year and welcoming in the new – we look back and forwards. This New Year we look back over COVID-19 and we look forwards over both Brexit, now (allegedly) done, and yet more COVID. 2020 saw huge changes for MMB and how we connect with you. We’ve moved all our output online, from increased blog posts to virtual workshops and seminars, to our two new online courses. Like many academics I have spent longer talking into my computer in the past nine months than in the previous nine years. I’ve adopted a range of video conferencing programmes, got better at chairing online meetings and hosted a number of online panel discussions. Data movement has substituted for physical presence.

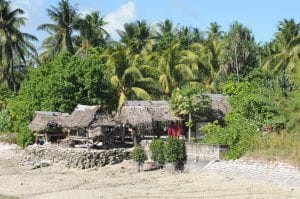

This learning has been very much about means of connection, but what about spaces of connection? In a recent short piece for the feminist journal Signs, Miriam Ticktin, a member of MMB’s Transoceanic Mobilities Network, argues that COVID has rendered human connections to be perceived and experienced as dangerous, privileging as ‘safe spaces’ the home and the nation. But for many people home and nation can be highly dangerous. Several MMB blogs in recent months have discussed the horrific rise in domestic violence and the continuing deportation and abandonment of people at borders and in detention centres. Ticktin seeks out emergent spaces of connection in the ‘feminist commons’ and suggests: ‘The question then is not how to isolate ourselves – our vital connective tissue with one another and the planet has been revealed by Covid19 in a whole new way – but which forms of connection to attend to and cultivate; and which ones to be careful of or replace.’

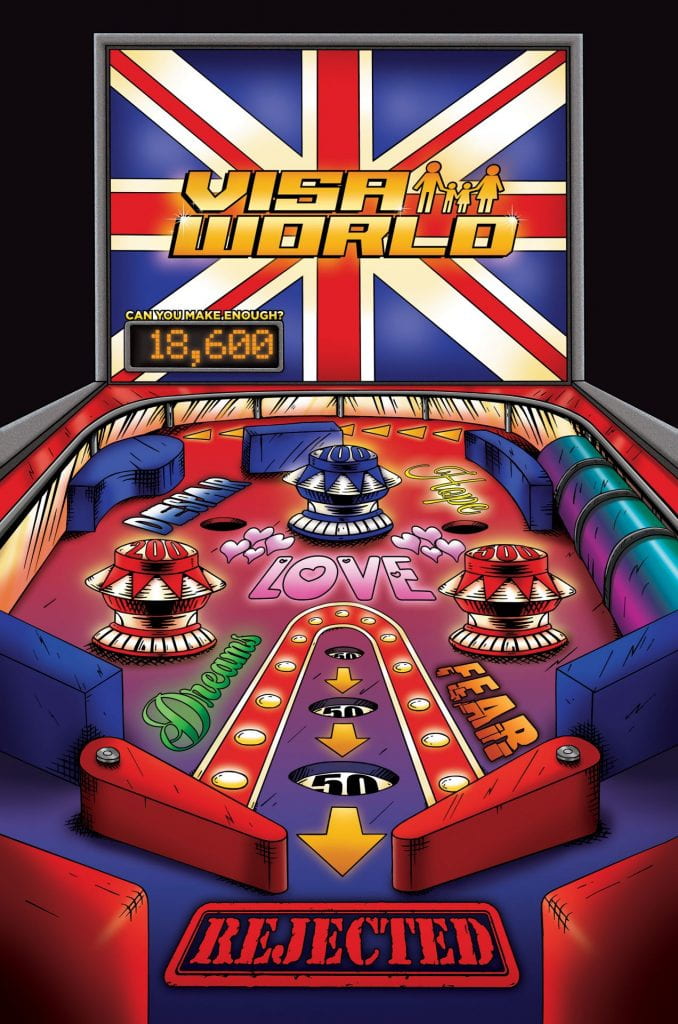

There are also forms of connection that we need to repair and recover, particularly in the context of the Brexit-induced friction that has turned mobile citizens into migrants. For those of us interested in migration and mobility, this exemplifies how the separation of citizens and migrants is political (and often racialised) and invariably obscures multiple and complex connections. COVID can help us think about these in new ways. Balibar (2002) famously observed that borders are ‘polysemic’ – they do not have the same meaning for everyone. UK citizens are accustomed to a version of the polysemic that enables relatively free global access for them – and highly restricted access for non-citizens to UK territory. Yet in December 2020 UK nationals themselves were subject to international travel bans, not because of Brexit (though that swiftly followed) but because of a highly virulent form of the virus. At the same time, the polysemic nature of borders is also revealed in the UK government’s quarantine exemptions for incoming travellers, which include hedge fund managers, senior bankers and senior executives involved in high value deals. While some people pass through borders, others are stopped.

COVID has also exposed internal borders that, for most UK residents had previously been invisible. Who would have thought this time last year that the Scottish and Welsh Governments would have forbidden cross border travel from England? We are being given crash courses too in local authority boundaries, previously barely noticed (turnout for local elections runs at about 35%). These boundaries have been given new meaning through the Tier system, which demarcates what level of restrictions residents are subject to according to their local authority.

For many people, then, it has taken COVID to realise how borders crisscross our lives. But for others this is old news. Administrative boundaries crossed unknowingly by millions every day are only too well known to those on state benefits and the homeless. In England, homeless people who do not have a connection to one local authority can be told they have to go to another for housing and the procedures and guidelines for doing so may also cover cross border issues in relation to Scotland and Wales. In the Netherlands, social assistance claimants can be sanctioned a month’s worth of benefit if they move without a ‘clear and good reason’ (Knijn and Hiah, 2019). In Turkey, some recipients of disability and elderly allowance cannot even move to a different street in the same district – if they do, social assistance is withdrawn for months. In Hungary, social housing claimants have to prove residence for a year in a local area, while in Portugal job seekers can be required to check in at the parish council every two weeks in order to confirm unemployment status. The boundaries internal to Europe – between EU member states – and internal to the British state – between its constituent countries, between London and outside, between different local authorities – afflict and are made visible to the homeless citizen and the welfare claimant, just as the state border afflicts and is made visible to the non-citizen.

COVID exposes this to all of us and, importantly, some citizens are policed more harshly during the pandemic than others. Black Lives Matter has foregrounded the violence meted out to Black people in the ‘wrong’ spaces, citizens or not. In the report Policing the Pandemic, Amnesty International found that across Europe, Black and ethnic minority people are disproportionately targeted by police with violence, discriminatory identity checks, fines and forced quarantines.

MMB is interested in making connections – between different disciplines and areas of scholarship, between theory and practice and across migrants and citizens, policy-makers, activists and academics. This is where we find the sparks that make us think in new and meaningful ways. In 2021 we will be making more spaces for these connections to grow – from online forums to communal gardens. Come and join us!