New writing on migration and mobilities – an MMB special series

By Laurence Publicover.

In 1607 three East India Company (EIC) ships set off on the company’s third voyage, aiming to break into the lucrative spice trade dominated by Portugal for the previous century. As the first to reach mainland India, this voyage has clear significance for histories of globalization and English (later British) imperialism. But it is also of interest to literary historians, as it provided the occasion for the first recorded performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Or at least, it might have done – the documentary evidence leaves plenty of room for doubt. In any case, this (possible) performance of Hamlet off the coast of what we now call Sierra Leone, perhaps before an African audience, is good to think with. It might, for example, prompt us to consider how Shakespeare’s works became both a tool for imperialism – his plays have found a prominent place in colonial curricula, including in India – and a means by which colonial subjects could ‘speak back’ to the imperial centre through adaptation and reinterpretation. If Shakespeare is a global playwright, then it seems apt that the earliest performance record we have of Hamlet – perhaps his most important play – relates not to London, but to a voyage that helped shape global history.

All this is very enticing. But as someone who works across Shakespeare studies and oceanic studies, I am also interested in this episode for other reasons. To borrow Hamlet’s words, what might have been ‘the purpose of playing’ during an EIC voyage?

The idea that literary culture shapes maritime culture – and vice versa – sits at the heart of Shipboard Literary Cultures: Reading, Writing, and Performing at Sea, a volume of essays I have edited with the social historian Susann Liebich (University of Heidelberg). Currently in production at Palgrave Macmillan, the book examines the literary cultures of vessels ranging from a man-of-war anchored off the coast of Plymouth during the English Civil War (1642-51) to the container ships that traverse our oceans today. Individuals explored within specific chapters include anxious migrants on the three-month ‘Australia run’ from England, a young girl on her father’s whaleship, troops travelling from New Zealand to Europe to fight in the First World War, and American college students circumnavigating the globe aboard the ‘Floating University’ around a decade later.

Our contributors demonstrate how, in their various ways, these seafarers came to terms with their situation through ‘literary’ strategies: by putting on plays, producing newspapers or circulating reading materials as a way of building morale and a sense of community; and through private acts of reading and diary-writing that, among other things, helped maintain mental health and personal identity in the extraordinary circumstances occasioned by sea travel.

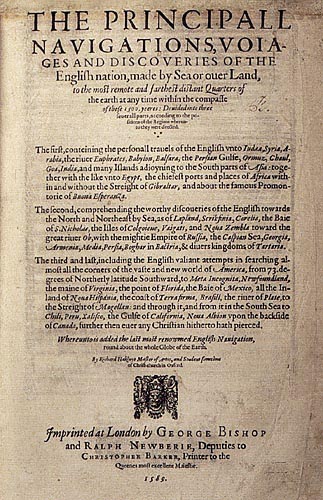

If mariners really did perform Hamlet off the coast of Sierra Leone in 1607, then this was not, in fact, the most significant way in which literary culture shaped the third EIC voyage. When floundering in mid-Atlantic and on the point of returning to England for fresh supplies, EIC officers decided instead to seek provisions on the West African coast after reading about Sierra Leone in Richard Hakluyt’s compendium of voyage narratives, The Principal Navigations (1589). What was this book – which includes narratives of mythical as well as actual voyages – doing on board? Did someone bring it along for just such an eventuality? Or was this the re-purposing of a book carried for other reasons?

If Hamlet was performed, then we must assume the seafarers were carrying a copy of the play, too: either the shorter 1603 version, or the longer 1604 version more familiar to us today. Was this copy similarly repurposed – carried as personal reading material, but transformed into a performance text when the need arose? And what was that need, exactly?

Some scholars have argued that the performance of Hamlet was designed to establish closer relations with the rulers of what was, for the EIC, a strategic stopping-off point on the journey around Africa. Given that plays were often performed before ambassadors in early modern London, this certainly seems feasible. But it is also possible that Hamlet was staged for the benefit of the English crew: as more than one contributor to Shipboard Literary Cultures argues, theatrical performance at sea could provide a welcome distraction – even a necessary release valve – for those cooped up together on a long voyage.

Over the next year I will be advising on The Hamlet Voyage, a project developed by the director Ben Prusiner that considers the wider resonances of the EIC voyage. The play, which is being written by Rex Obano and features puppetry directed by the Delhi-based Anurupa Roy, will be performed aboard The Matthew – a replica of the ship in which John Cabot crossed the Atlantic in 1497 – at the 2022 Bristol Harbour Festival.

We are interested in how the 1607 voyage points forward to the British colonization of India; we wish also to explore the fact that, only a few decades earlier, an English ship had carried enslaved people from Sierra Leone to the Caribbean (this was the voyage read about in The Principal Navigations). Sierra Leone was later to become a key node in the triangular trade.

In these ways, then, the 1607 voyage asks us to reflect on the history and the legacy of British imperialism. But it also asks us to think about the wider experience of crossing oceans. What is it like to head towards an unknown destination, losing sight of land for weeks at a time? What, in such circumstances, might help us assuage our fear, or our boredom? What might help us build relationships with those sharing our experience? What might help maintain a connection with home?

Different conditions of voyaging will, of course, determine the answers to these questions. But across different centuries, cultures and vessel types, literary activity – and perhaps especially communal performance – has helped people cope with the hardships and perils of maritime mobility. Studying the records of such activities can help us imagine the experiences of those who crossed oceans in the past; and in turn, it may help us overcome the ‘seablindess’ that – alongside other factors – prevents us from thinking about those who cross them today.